Community Sports

Legendary Doris Heritage just loved to run

Former Gig Harbor resident Doris Heritage , a chart-topping female long-distance runner in the 1960s and ’70s, is known for once being the best in the world. On a recent afternoon, Gig Harbor Now spoke with Heritage, now 81 and living in Stanwood, to discuss her legendary career that brought worldwide attention and fame to the South Sound.

When describing an athlete, the word “legendary” is seldom used, and when it is, it should mean something.

There is only one athlete, male or female, who had a career that was legendary enough to represent Gig Harbor on Sports Illustrated’s Top 50 Athletes from Washington list.

Her name is Doris Heritage, who at one time was the best female long-distance runner in the world and the only one to win a remarkable five cross-country world championships in a row, from 1967 to 1971.

Competed in two Olympic Games

Heritage made two Olympic teams (Mexico ‘68, Munich ‘72) and missed a third (Rome ‘60) by .01 seconds when she was just 18 years old. She was also the first woman ever to run a sub-5-minute mile indoors, shattering the barrier by eight seconds.

At one point, the girl from Gig Harbor owned every national title, from the 440-yard dash to the 1-mile race. She was the U.S. champion in the 440-yard dash, 800 meters, 1,500 meters, 3,000 meters and a five-time national cross-country champion. If one stopped right there, the legendary status would fit like a glove, but there’s so much more that this remarkable woman accomplished.

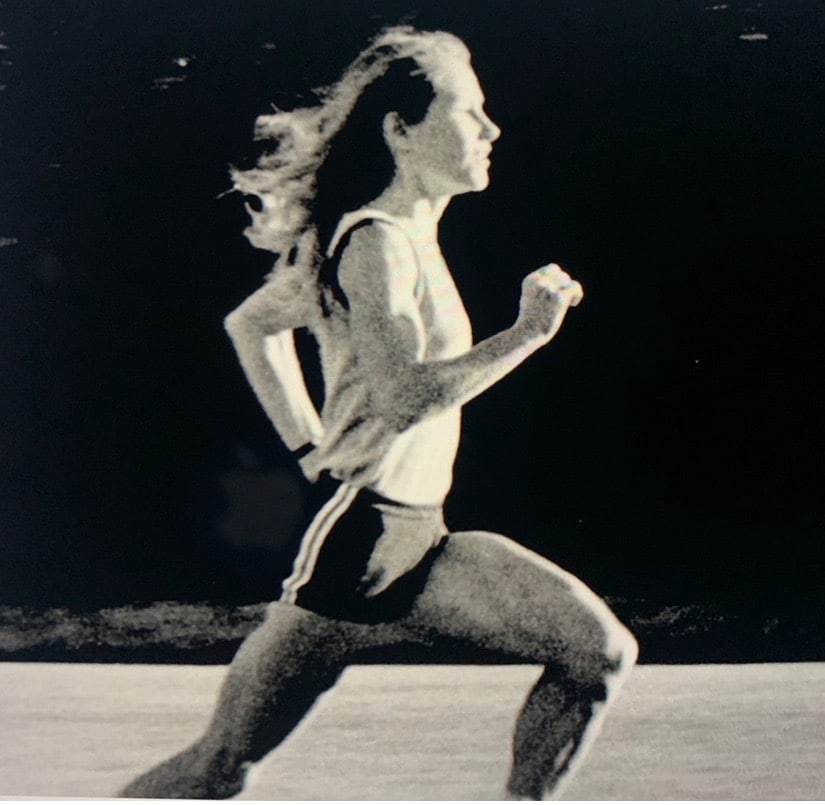

Heritage’s speed and endurance are evident as one watches a YouTube video of her sub-5-minute-mile race from 1966. There’s an old saying in sports that the videotape doesn’t lie. Her tape only tells the dominant truth of a runner who had to be seen to be truly appreciated. It shows a boundless runner who was faster toward the end of the race than the beginning.

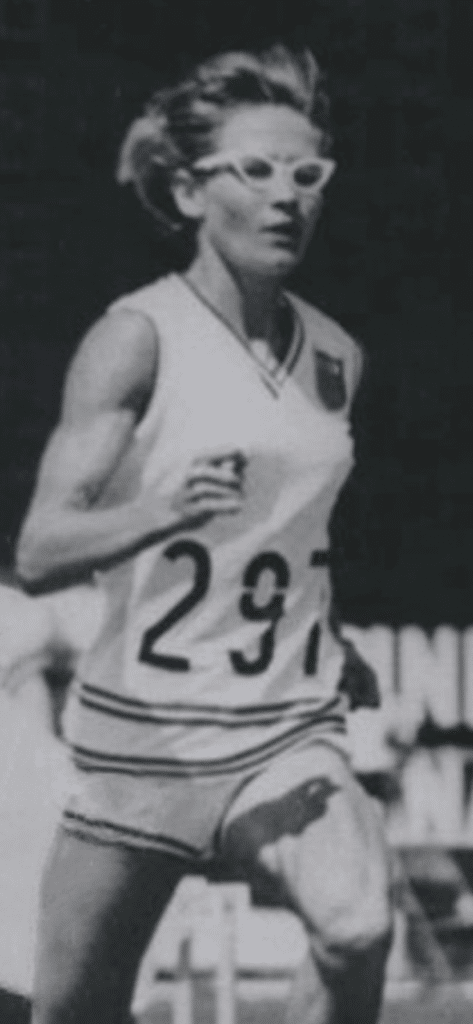

Doris Heritage won five consecutive world cross-country championships from 1967 to 1971. Photo courtesy of Doris Heritage

Heritage displays explosive speed and uses quick bursts to pass several runners before an all-out sprint down the homestretch that left pre-race favorite Roberta Pico far behind. Heritage crosses the finish line in 4:52, setting the indoor world record in front of an international television audience.

Ran with style

The tape also reveals a woman with style, with a cool, coiffed hairdo, fashionable cat glasses and million-dollar smile. One of the first female athletes in America to garner athletic attention, she displayed a natural blend of femininity, grace and sophistication with a muscular and toned body.

She blended all of that with a competitive fire that had not been seen before by many sports viewers.

“I always thought about representing women in a positive light and I thought it was important to be a good athlete but always present yourself in the best way possible,” she said of her stylish look.

Heritage’s legendary career brought worldwide attention and fame, but now, outside of local running circles, few in Gig Harbor know of her amazing accomplishments. She has unfortunately gone from a legendary hometown figure to a somewhat anonymous one as the years have slipped by. I stumbled upon her name while checking Sports Illustrated’s list, where she was ranked 35th, and was happy to find her alive and well at 81 years old, living in Stanwood with her husband of many years, Ralph Heritage.

When contacted for this story, Heritage’s excitement was as evident as any 16-year-old interviewed for the first time. She energetically conveyed her deep love and affection for the Gig Harbor area and the desire for her story to be retold, especially before the onset of dementia that she candidly admitted to and has been diagnosed with runs away with more of her cherished memories.

“I have so many friends that still live in Gig Harbor,” she said. “I really loved growing up there. It is such a beautiful place. There are a lot of winners from that town. This will be wonderful. My memory is not quite the best right now, but I’ll try very hard to do my part and tell you all that you need to know.”

Researching her career and the trials and tribulations of excelling in a male-driven sport and heartbreaking events in Olympic competition, one discovers an inspiring story of determination through obstacles and disappointment that seem like a Hollywood script just waiting to happen.

Grew up near Fox Island bridge

Born Doris Severtson in 1942, she grew up across from Fox Island and was raised by parents Henry and Villa Severtson, hardworking farmers who harvested 125 different blends of chrysanthemums on their 25 acres. If one were heading east across the Fox Island bridge toward Gig Harbor, the land just on the right side is the old Severtson homestead where Doris was raised.

Doris Heritage grew up on her parent’s farm near the east end of the Fox Island bridge. Photo courtesy of Doris Heritage

As a child helping her father and younger siblings Ron and Louise, she would often gaze with amazement across Puget Sound at majestic Mount Rainier. The first-grader would dream of climbing its 14,410 feet and then becoming the first woman to summit Mount Everest. Her young mind saw opportunity without limits as her imagination didn’t adhere to the restrictions placed on females of the era.

While many youngsters just dream, Doris took action. To scale Mount Everest, she would need to be in peak physical shape with exceptional lung capacity. So, after waking up early to work, she began daily training as a 7-year-old on the sandy beach before running the steep inclines of her property, alone and determined.

“I felt that I was truly born to run and was so excited when all my friends got bicycles for Christmas, not because I wanted to ride them but so I could run beside them everywhere they went,” she said.

On elementary school playgrounds and in junior high, Heritage noticed that no one, boy or girl, could keep up with her pace.

Couldn’t participate at Peninsula

Heritage moved on to the only high school in the area at the time, Peninsula. By then, through years of self-training, she had developed a unique style. She ran very vertically with shoulders back and high knee extension attained from years of running in the heavy, wet, beachfront gravel. Her stride was light, quick and darting. Unfortunately, nobody at Peninsula would ever see her race.

The Seahawks had a future five-time world champion in their midst, but nobody knew it as she was barred from competing. A league-wide rule allowed only male runners to compete in track and field events. Running was considered an obstacle to childbearing, which was apparently thought of as a female’s main purpose in the late 1950s.

Doris was forced to remain anonymously on the sidelines, a victim of gender bias derived from exclusivity and misinformation.

“During my time at Peninsula, I forgot about that fast runner and long jumper,” Heritage said. “Except for the president’s physical fitness test one day of the year, I never ran at school.”

Neighbor supported her

Her fortunes began to change when an open-minded, 72-year-old local man named Robert McCory saw Heritage running outside several times and decided, as she put it, “That little neighborhood girl just needs an opportunity.”

McCory knew little about running or training methods, but he had an eye for talent, and he knew determination when he saw it. He also had a big heart and wanted to try and help Doris succeed. Without him, the greatest runner of her generation would have slipped into obscurity.

The Severtsons were reluctant at first to allow her to train with a stranger, but understood their daughter’s passion for competition. They allowed McCory to drive Doris to flat, downtown Tacoma streets. Once there, he would have her sprint several blocks down and back, as fast as she could, without stretching. Without proper warm-ups, she would cramp and suffer side aches but would climb back in the car undeterred.

After the sprints, McCory would take her to a Point Defiance garden and have her long jump into flower beds in a routine that might be laughed at today. She was happy to endure a few suspect training methods because she finally had something that every athlete needs — someone who believes in them.

McCory bought Heritage her first pair of track shoes, got the Elks Club to sponsor a makeshift track team and purchased her first uniform. He would pay for her entry and drive her to regional races. The young girl from Gig Harbor did the rest.

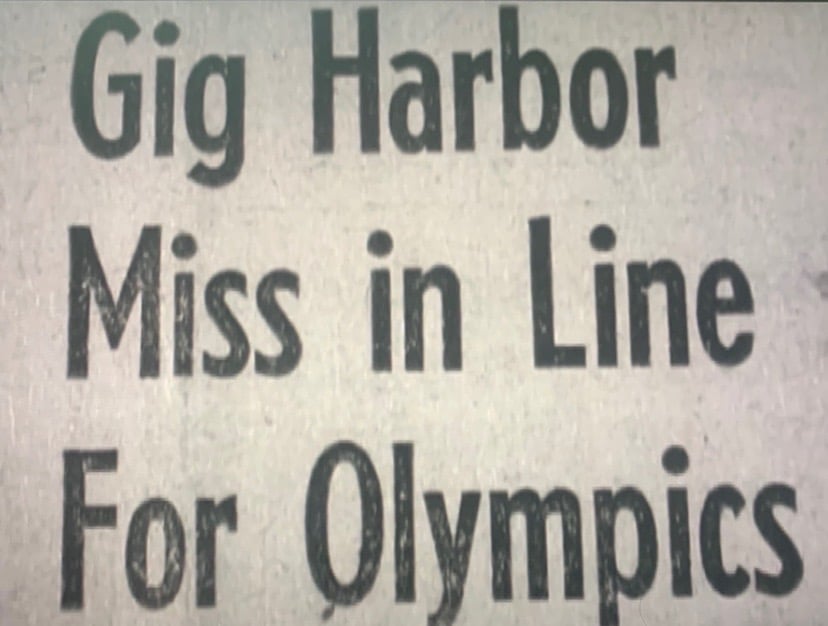

Gig Harbor teen Doris Heritage set a national record in the 440-yard dash as a 17-year-old. Photo courtesy of Doris Heritage

Once on the track, the 110-pounder was a blur. It became apparent that she had national-level talent. McCory’s time and efforts were rewarded when in only her first few races, the 17-year-old ran the fastest 440-yard dash ever by an American female to shatter a national record.

At 18, Heritage continued to excel. Suddenly, she was in line for the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome after running the third-fastest 800 meters in America. The U.S. team only took one athlete in the event. Heritage finished second by just .01 seconds at the Olympic Trials. To miss an Olympic team by a blink of an eye was Heritage’s first heartbreaking setback. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be her last.

Ran with the guys at SPU

She chose to attend Seattle Pacific University where women didn’t have a team, but Heritage could train with the men’s team under legendary coach Ken Foreman. She routinely ran with the men’s team and her times continued to improve because of it.

“I would like to say that I was treated wonderfully by Coach Foreman and those guys,” she said. “Throughout my career, men were so friendly and kind to me and they really helped me run a lot faster.”

The long-distance training would pay off as Heritage entered European competition with its long tradition of cross-country racing for the first championships that included women. She won the 1967 Cross Country World Championships at Barry, Wales, in the United Kingdom. She turned heads with her abilities and style as cross-country racing was widely respected and celebrated in Europe.

Heritage won her second world title in a row in 1968 at Tunis, in Northern Africa, in dominating fashion. Her endurance and ability to gain speed throughout the race was appreciated by the running elite.

“It was a pretty exciting time of my life,” she said. “Winning isn’t everything, but I won because I worked harder than everyone.”

‘Bumped’ to fifth in Mexico City

Up next came the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. Heritage entered the 800-meter race as the favorite by way of her fastest qualifying time. She was in good position to claim a gold medal, but was illegally pushed off stride by another runner.

“I remember that I was in perfect position and feeling really strong coming into the homestretch,” she said. “I was about to make my move when another runner locked her arm around mine for a couple of strides before pushing me. I stumbled for two or three steps and lost all of my momentum. By the time I recovered and got back up to speed, it was too late. I finished fifth.”

On the phone, Heritage’s voice trailed off with the sorrowful recollection of that day before saying, “Some things I can’t recall now, but unfortunately I remember that race very clearly. I had the ability to win the gold medal, but I didn’t, and that was a really tough one to get over.”

In 1969, it was back to Europe for a chance at a threepeat at the World Cross Country Championships. Heritage won gold in Clydebank, Scotland. She followed it up with the first world championship for women on American soil with a 1970 win in Frederick, Md. In 1971, she won her fifth championship in San Sebastian, Spain, by 13 seconds.

“It was special because I was the first to represent women runners and I wanted to do it the right way,” she said.

Later that same year she set world records in the 3,000 meters and the 2-mile run. The five consecutive world cross country titles has never been duplicated.

By then, she had become somewhat of an international star.

Not paid a penny

“I just loved running over there in Europe. Everybody was so friendly and knowledgeable,” she said. “I got to travel all over the world, but to think that I never received a penny from running still surprises a lot of people.”

It wasn’t about the money, though. It was about the challenge.

“When you put yourself on the line in a race and expose yourself to the unknown, you learn things about yourself that are very exciting,” she said.

Heritage went on to claim her second Pan Am Games silver medal in 1971 in the 800 meters before qualifying to represent the Americans again, in the 1500 meter-race at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Germany.

She was excited for another chance at gold and the opportunity to race at a new, longer distance. Gig Harbor businesses helped her finance the trip, donating and putting out jars at banks with the slogan “Dimes for Doris.” Eide’s store, Borgen Lumber and Uddenberg’s grocery customers filled jar after jar with spare cash and change to help Heritage pay for her Olympic journey.

Local citizens and businesses had a “Dimes for Doris” fundraiser to help send Heritage to Munich for the 1972 Olympics. Photo courtesy of Doris Heritage

Olympics disaster II

Heritage made the trip to Munich and was in peak condition when disaster struck again. She suffered one of the cruelest fates of any Olympic athlete. An official had placed a moveable metal curb on the track to prevent long jumpers from hitting it. As she walked onto the track before warm-ups and was observing a full stadium, Heritage didn’t see it and stepped on it awkwardly, breaking five bones in her foot and tearing a ligament. That ended her Olympic event, as the favorite hobbled off the track before the race ever started.

Fortunately for her now, that memory isn’t as sharp. All she could recall from that day is that she hurt her foot somehow, saying with an easy laugh, “Oh well, I had a lot of good days running and injuries are an unfortunate part of sports.”

It would take more than mental toughness to survive that excruciating experience and thrive again, but Heritage did.

Though her chase for an Olympic medal ended that day and her speed was declining with age, Heritage still had her everlasting stamina, toughness and willpower. She proved that in her remarkable victory at the 1976 Vancouver (Canada) City Marathon, where she ran 26.2 miles in a blazing time of 2:47:35, though she had never trained or ran a marathon in her life. Her coaches felt that distance would rob her of her natural speed. How good was her time? For perspective, the winner of the 2009 event 34 years later only ran it 29 seconds faster.

Runner-up in NYC Marathon

The win in Vancouver earned Heritage an invitation to the world’s most prestigious marathon in New York City later the same year. A legion of young women in the race were Heritage fans who had been inspired by her to take up the sport and considered her as a living legend. But Heritage wasn’t ready for the retirement tour just yet. She was gaining on the leader at the end and finished a close second. The 34-year-old Heritage proved she was her generations’ most accomplished runner over various distances.

“I appreciated becoming a role model and I wanted to do all I could to advance women’s opportunities,” she said.

A true pioneer for female runners, Heritage was rewarded by being inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame and the national Distance Running Hall of Fame. The locals took notice as well when the Seattle Post-Intelligencer gave her their “Man of the Year” award in an unprecedented ceremony and then had to rename the award “Athlete of the Year” from that moment on. The state followed by naming Heritage as the Washington State Legislature’s “Woman of the Year.”

Heritage gave back to her sport in many other ways. She used her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education from Seattle Pacific University to become a beloved teacher in the Shoreline School District, spending 37 years as a junior high teacher. She also logged 39 years as a cross-country and track coach at her alma mater, where she built a legendary coaching career.

Doris Heritage coached 20 All-Americans in 39 years at Seattle Pacific University. Photo courtesy of Doris Heritage

Continued success in coaching

At SPU, an NCAA Division II school, she took over for a retired Foreman and continued its national reputation for excellence. She coached seven conference championship teams in a 12-year span and was named the conference coach of the year seven times. She coached 20 All-Americans, seven female NCAA champions and countless athletes who absolutely adore her positive and friendly style.

Heritage was also selected as an assistant track coach for one of the most talented and revered U.S. track and field teams in American history — the 1984 Olympic team that competed in Los Angeles. It featured Carl Lewis, Edwin Moses, Florence Griffith Joyner, Jackie Joyner-Kersee and long-distance standouts Alberto Salazar and Mary Decker.

Decker ironically suffered a fate such as Heritage’s when she tripped and fell during her race to squelch her Olympic dreams in a scene many runners still recall.

“I felt so bad for Mary as I knew exactly what she was going through,” Heritage said.

Heritage also was a coach for the 1992 U.S. World Championship team and was selected as the second woman ever to be inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame as a coach, in 1999.

A hip injury is about the only thing that ever slowed Doris down as the degeneration of her joint caused her to undergo a replacement surgery a few years ago. Until then, she had run twice a day every day for 40 years as her biggest joy seemed to be the harmonious relationship with the outdoors that running brings.

“I believe in prayer, and I have prayed that my life without running won’t be that hard and so far I feel fine concentrating on my athletes rather than myself,” she said.

Doris’ ‘Final Mile’

KOMO-TV news cameras and anchor Eric Johnson documented Heritage’s final run at SPU as hundreds of former runners and countless friends showed up to run with her in an event called “Doris’s Final Mile.”

As she finished her run that morning with impressive form, Doris Heritage wasn’t sad but optimistic, and laughed loudly while being surrounded by family, friends and past athletes. She still had the bright smile and exuberance of a woman half her age, who has lived a full and wonderful life. She hopes that one day in the distant future her tombstone will read, “She just loved to run.”

Though the hip replacement took away her passion and her mind may dull some memories, Heritage said she will never forget her beautiful birthplace and all the love and support she encountered in Gig Harbor. Hopefully after reading about the wonderful person that she is and the incredible runner that she was, her hometown always remembers her as a true legend and Doris always remembers how proud her community is to call her one of its own.