Business Community Environment Government

More growth seen for Gig Harbor — but not like in the 2010s

Gig Harbor had a moment of shock and awe last year when the 2020 U.S. Census results came in.

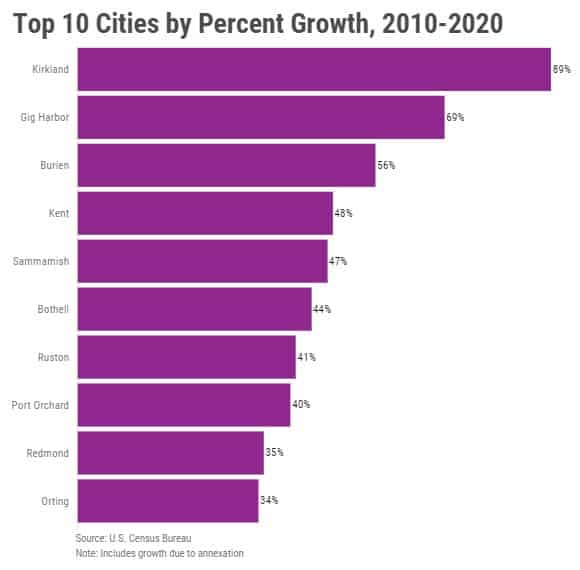

The Census showed the city’s population soared by a staggering 69 percent in the previous 10 years. Gig Harbor went from 7,126 residents in 2010 to 12,029 in 2020.

“As of 2020, the City had reached its 2030 employment growth total by 2,666 jobs, and as of 2020, exceeded its population growth target by 740,’’ wrote Pierce County’s Growth Management Coordinating Committee (GMCC), which tracks such matters.

Gig Harbor habitués could already see that many trees were coming down and many new homes and commercial buildings were going up. Clearly, this once-sleepy fishing village was growing, and fast.

But 69 percent? How did that happen?

And: could it happen again?

Workers frame the upper story of a new home off Burnham Drive recently. Vince Dice

To find out, we interviewed key players past and present: Gig Harbor City Administrator Katrina Knutson, Gig Harbor Principal Planner Carl De Simas, former Gig Harbor Mayor Jill Guernsey, and developer Jon Rose.

Each person has his or her own perspective, but collectively they help bring into focus the complex world of predicting, planning and managing population growth and associated development.

Population growth unlikely to continue at this rate

Taking the second question first — could we have another sudden tsunami of population growth? — city leaders say that’s unlikely.

The confluence of forces that turbocharged the city’s recent population growth is no longer in place. Meanwhile, policies and procedures in place now should help impede runaway growth.

There will be growth, Knutson and De Simas acknowledge, but it will be slower. And it will be carefully calibrated, in accordance with the Ur-text for city, county and state planners: the Washington Growth Management Act (GMA).

The GMA, passed by the Legislature in 1990, confines major development and population growth to urban areas with high-density housing and commercial space.

New construction on 62nd Court NW, just outside Gig Harbor city limits, as seen through a fence on Hunt Street.

The idea is to prevent urban and suburban sprawl and protect rural areas, with their critical farms and fields, and backcountry wilderness, with its sensitive fisheries, wetlands and wildlife habitats.

Population growth and the comp plan

Just what Gig Harbor’s population will be in 2030, when the next U.S. Census takes place, is unknown. But, according to city officials, low target growth figures for Gig Harbor will be finalized by December 2024, when Gig Harbor’s updated Comprehensive Plan is adopted.

The plan is subject to approval by the intergovernmental Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC). Nearly 80 cities and towns are dues-paying members. So are nine federally recognized tribes, port districts, King, Kitsap, Pierce and Snohomish counties, and several state agencies.

The PSRC has ambitious goals. It recently adopted a plan called Vision 2050, to manage growth through 2050, when the Puget Sound area’s population could reach 5.8 million. It was 4.2 million in 2019.

The PSRC is largely funded by the federal government and governed by elected officials from member communities such as Gig Harbor. Member cities and towns must accept the council’s growth management targets. Ultimately, they must comport with the state GMA.

According to a draft plan shared with Gig Harbor Now, the city of Gig Harbor is expected to grow by 2,200 people by 2044. That does not including neighboring unincorporated communities.

That would give Gig Harbor 14,229 residents, per Pierce County’s estimate. Given the fluid nature that makes controlling population growth a moving target, that degree of specificity may not be possible.

New homes are being sold faster than they can be built in Gig Harbor. Vince Dice

The why and how of population growth

City Administrator Katrina Knutson says “smart demographers’’ on the state level are busy tracking and forecasting growth. Their work, she says, helps officials throughout the state craft plans and policies to manage future population growth and development.

The state’s demographers take a number of factors into account, according to Knutson. She was the city’s community development director for three years before becoming city administrator on June 13. “They consider birthrates, deaths, out-migration, immigration.’’

Newcomers traditionally move to Washington for work, school, retirement. Many are attracted to casual, outdoorsy Pacific Northwest lifestyles.

Nowadays, says Knutson, some people relocate here for a new reason: To escape the punishing heat, prolonged droughts and devastating wildfires plaguing much of the nation. She calls these new newcomers “climate refugees.’’

Climate change, she suggests, could pose problems that didn’t historically exist in cool, rainy, relatively uncrowded Washington. Among them: shortages of drinking water in a hotter, drier environment.

Gig Harbor North annexation

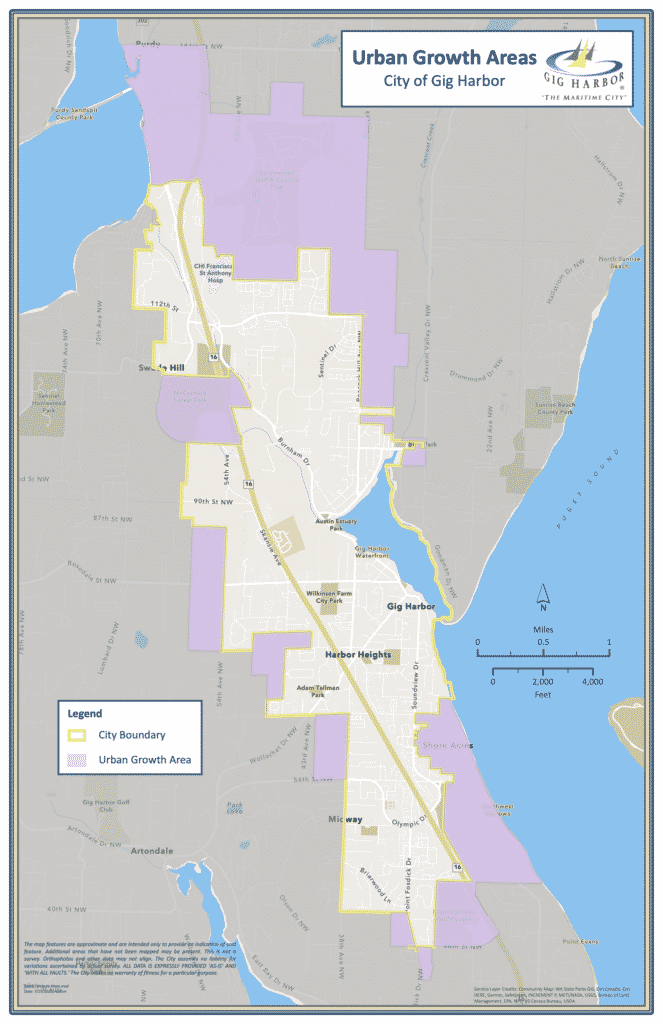

Gig Harbor took a quiet but significant step toward its recent fuel-injected growth back in 1998, before climate change was top-of-mind. That’s when the city annexed a 707-acre parcel of forested land in Gig Harbor North. Washington cities often grow by annexing designated Urban Growth Areas, or UGAs.

“The population of the area was zero, because it was all trees,’’ explains Jon Rose, former president of the Olympic Property Group (OPG), which managed and previously owned Gig Harbor North.

New homes being built in the North Creek development off Burnham Drive. Annexations and growth in this area helped drive a spike in population in Gig Harbor during the 2010s. Vince Dice

The area eventually bristled with shopping centers showcasing a mix of big-box stores, chain supermarkets, informal eateries and small, locally owned businesses. But not right away.

“It takes a long time to bring a project like that to fruition,’’ Rose observes of the ambitious development, which OPG dubbed the Village at Harbor Hill. “We brought in the YMCA and Costco, both in 2006,’’ he notes. That was eight full years after the 1998 annexation.

In addition, Rose recounts: “We built 560 single-family homes and 500 multi-family dwellings. We also created some parks.’’ The initial slow-moving buildout of Harbor Hill then picked up velocity.

More people, more traffic

That burst of activity transformed Borgen Boulevard, which became a major road early this century as development intensified near State Route 16.

The result was the Borgen Boulevard we see today. Festooned with busy roundabouts and defined by the drone of heavy traffic, it is one of the busiest roads in Gig Harbor.

Growth and expansion of residential housing in an eight-acre section of the Village at Harbor Hill hit a speed bump in November 2017, when the Olympic Property Group sued the city of Gig Harbor. The cause of the commotion was a Gig Harbor ordinance which set new traffic impact fees. OPG claimed increased fees made finishing the Village at Harbor Hill Village project “financially impractical.’’

New homes being built in the Skansie Point development near the corner of Hunt Street and 46th Avenue in Gig Harbor.

The city and Rayonier, OPG’s corporate successor, settled in September 2020. In a kiss-and-make-up press release issued jointly by the city and Rayonier, terms were outlined. The company would save $1.1 million in fees. In return it would replace streetlights removed during construction and upgrade them to city standards, install pedestrian safety features and build the last pair of Borgen’s six roundabouts.

Cities pressured to absorb population growth

The development of Harbor Hill was perhaps the biggest single reason Gig Harbor’s population mushroomed in the past decade.

Some of Harbor Hill was planned and built during the tenure of former Mayor Jill Guernsey. A lawyer and 44-year resident of Gig Harbor, Guernsey was the city’s top elected official from 2013 to 2017.

The PSRC informed all Puget Sound cities they “had to plan to accommodate projected growth populations,’’ Guernsey remembers.

“The population figure was not the City’s figure; it was the figure given to the City by the PSRC, and with which the City had to comply,’’ she writes in an email.

“Many applications for residential subdivisions were filed in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and because of the (weak) economy, the build-out period was extended by the state,’’ Guernsey continues.

Among the delayed subdivisions were projects along Burnham Drive and on or near Borgen Boulevard. “Harbor Hill was a bit different in that it was approved as a master planned community – aka large-scale development with both residential and commercial development,’’ Guernsey remarks.

“Understandably, many of these developments were largely unnoticed until roads and houses started to appear,’’ she continues. “And the public was not happy. I don’t blame them.’’

Gig Harbor steered growth away from downtown

In a pivotal decision, Guernsey says that Gig Harbor took a different path than some Puget Sound cities that built condominiums atop downtown retail spaces to absorb growing populations.

Instead, to preserve scenic views and space downtown, the city concentrated growth away from the picturesque harbor to Gig Harbor North.

Unincorporated areas of Pierce County also saw population growth, Guernsey notes. But the GMA kept growth there lower than in cities. Still, many locals who don’t live in Gig Harbor shop in the city, work in the city and drive on city streets. “We are all a part of the greater Gig Harbor area.’’

Rightly or wrongly, Jill Guernsey was seen as a robustly pro-growth mayor at a time when voters alarmed by surging development were turning against rapid growth. That perception stuck to her and she paid a political price for it.

Penalties for growing and not growing

She ran for reelection in 2017 against jewelry designer Kit Kuhn. He campaigned on a low-growth platform and won 71 percent of the vote. A largely slow-growth city council took office.

Things did not always go smoothly for the new mayor and council. In 2018, the state admonished Gig Harbor for enacting a six-month moratorium on residential construction within the city. Not in keeping with the GMA, state officials declared.

Gig Harbor stuck to its guns, and today’s Soundview Forest Park replaced what would have been a residential development.

There’s risk in challenging the state. Carl De Simas says withholding some tax revenues and blocking grant money give the GMA some teeth when state officials choose to use them.

Homes under construction at The Cove, a development near Hunt Street and 38th Avenue in Gig Harbor. Driven in part by regulations and annexations, the city of Gig Harbor grew by 69 percent in the 2010s.

Kuhn didn’t seek reelection in 2021. Councilmember Tracie Markley, running unopposed, became mayor this January.

Controlling growth, not stopping it

With history in mind, city leaders are determined to control future growth without stopping it cold. Gig Harbor needs jobs, housing and tax revenue that comes with growth, they say. It doesn’t need runaway growth.

Pierce County, like the state GMA and the regional PSRC, also has a say in how Gig Harbor grows. Adding to the multiple overlapping agencies, agendas and acronyms in the specialized planning sector is the aforementioned Growth Management Coordinating Committee (GMCC).

According to a GMCC report, Gig Harbor has a target figure of 1,000 new housing units by 2044. Additionally, gains in employment should account for 2,747 more jobs by 2044.

Some projected growth could come from designated Urban Growth Areas through annexation. There are 13 UGAs located outside city limits. If the city council’s April 14 study session is any indication, the city is not chomping at the bit to annex UGAs. It isn’t ruling it out, either.

Map of Gig Harbor city limits and urban growth area. Courtesy of city of Gig Harbor

In a 92-page April 2022 draft study by Seattle’s Berk Consulting shared with Gig Harbor Now, only one of the 13 UGAs would initially bring significant tax revenue to the city. Most others would cost the city money in the near term due to the expense of extending services such as sewer lines and policing.

Prosperous Canterwood would be the strongest candidate for annexation, thanks to its existing upscale housing. But much of Canterwood is a private golf course, which would presumably be off-limits to additional development.

The weakest UGA candidate? Purdy, according to Berk Consulting. The community has a weak tax base, needs to upgrade storm water drainage and uncertainty exists about fire flow — how much water would be available to fight fires.

On the horizon

Overall, local officials and planning professionals appear to be slow-walking future growth as much as they reasonably can. The hope is to prevent another population and development boom.

Katrina Knutson says, “We do know that growth is a big concern for a portion of our population. We want to significantly slow growth, we don’t want to stop it,’’ adding, “We have no outstanding development plans. We don’t have any outliers.’’

That said, some long-pending, much-discussed developments remain in the pipeline.

One of them is the proposed city sports complex planned for Gig Harbor North. The 30-acre development, championed by Guernsey when she was mayor, won’t add population but it is expected to bring in more traffic to the city.

Village at Harbor Hill

Another notable unfinished development is the Village at Harbor Hill.

Town and Country Market pulled out of the project, slated for an eight-acre parcel at Borgen Boulevard and Harbor Hill Drive. That delayed plans for the muti-use development.

Rose, now vice president real estate for Florida-based Rayonier, says flatly, “We have to find a grocery, or the whole thing breaks down.’’

Additionally, expansion of the Heron’s Key senior living facility on Borgen Boulevard is on tap. The project is not yet shovel-ready, though. The city has approved the exterior design of the project. It is expected to go forward in the next three or four years.

That’s not all. The biggest challenge for managing development and population growth will come when the economy comes roaring back again. Today’s staff shortages, inflation and supply chain disruptions won’t last forever. In three years, maybe five, things could look very different. What then?

That’s the great unknown facing Gig Harbor and an increasingly popular and populous Washington.

Only Kirkland grew at a greater rate, and that was because of a huge annexation. Courtesy of Puget Sound Regional Council