Community Environment

The sinking of the Walrus in 1963 was a disaster averted

Have you heard about the sinking of the Walrus? It was only one of the greatest maritime near-disasters in Puget Sound history.

There’s no memorial to it, as not-quite-calamities don’t usually get one. But among the survivors, and those with them at Catholic Youth Organization’s (CYO) Camp Blanchet on Raft Island in the summer of 1963, it’s a misadventure imprinted on memory.

It all falls apart

Mary Harvey Ancich still remembers standing on the deck of the Walrus more than 60 years ago, trying to get a better view as the 33½-foot converted military landing craft chugged across the calm waters of Carr Inlet. The late-afternoon sun warmed the crowded boat’s passengers, still spirited on the voyage home from an overnighter on the Key Peninsula.

The Walrus at dock. Photo provided by family of J. Gordon “Gordie” Hamilton, former CYO director of

summer camping.

“We were 14 years old, with friends, on an adventure in the Walrus! So, we were full of energy and anticipating our return to camp,” recalled Ancich, now a retired school secretary living in Seattle.

That’s when she glanced toward the open engine room and saw water gushing in where a piece of the craft’s armor plating — its outer wall — had snapped off. In an account published later, J. Gordon Hamilton, the CYO’s director of summer camping, explained: “due to the force of the water, because the ship was underway, the remaining portion of the armor plate on the port side gave way, taking with it the under planking structure of the ship.”

In other words, at 4:45 p.m. on Aug. 12, 1963, the good ship Walrus fell apart around them.

Walrus goes down fast

It’s estimated that the ship disappeared completely within 60 seconds. What happened in that minute helped keep that voyage home from Penrose Point State Park from becoming a tragedy.

For the campers and probably also for their counselors, the absence of true “adults” on the outing was an aspect that made it all the sweeter. Of the 26 people onboard, Ancich and 19 others were young teen girls attending Camp Blanchet, looking forward to starting high school in a few weeks. All but four hailed from Seattle. Four other women — none older than 20 years — were counselors, and two young men, ages 23 and 18, served as pilot and engineer.

Now was the time for the youthful leaders to prove their mettle. Cool-headed counselors and crew found the lifejackets (there were enough for every camper, but not for every person in the boat). One of the crewmen salvaged a 60-foot anchor rope tied to a ring buoy that would prove useful once in the water, for keeping the group together.

The front page of The News Tribune newspaper of Tacoma on Aug. 13, 1963.

“The water was very cold,” Ancich remembered. “I don’t panic and I don’t recall any pandemonium. I do recall that all the campers had entered the water except for two of the campers who couldn’t swim. They were afraid of going in the water, so the counselors ended up jumping in with them.”

Hail Mary

Everyone went into Puget Sound fully clothed and began the chilly swim to Deadman’s Island (now Cutts Island State Park), a half mile to the north.

“I recall holding onto the rope and saying the rosary as soon as we started our swim to the island. Then we switched to singing,” Ancich said.

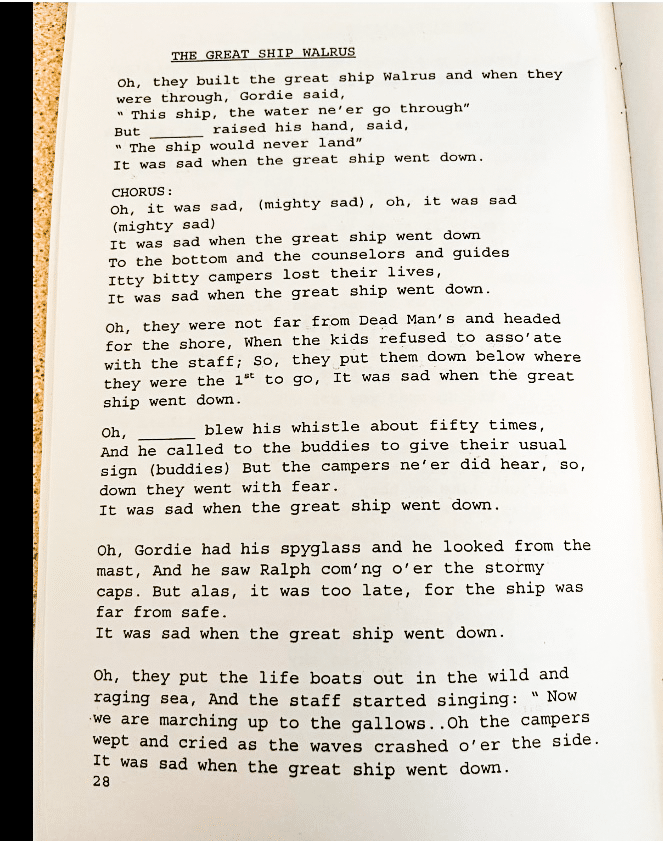

The group didn’t sing just any songs — they sang camp songs, “including the one about the Walrus (which sinks in the third verse of the song, though nobody ever really expected it to happen),” according to The News Tribune’s article about the incident, which ran under a front-page banner headline.

When they made it to the small island, Ancich lay on the warm rocks, trying to stop shivering. Hamilton, the CYO camp director, reported somewhat proudly a few days later in the Catholic Northwest Progress that upon exiting the water, the girls began praying aloud. “The ‘Hail Mary’ rang out 30 times before they remembered to say an ‘Our Father’,” he wrote.

Boat brigade brings campers home

Deadman’s Island lies close enough to the Rosedale shore that hollering carries across the water – especially the combined effort of 26 young, distressed voices. After prayer, yelling for rescue commenced. John King, a mainland resident, heard them and rowed out to Deadman’s.

Finding the castaways, he returned home, notified the U.S. Coast Guard, then rounded up neighbors to bring a boat and shuttle the campers, counselors and crew off the island, according to published accounts. Phone calls summoned Camp Blanchet personnel to come and get the survivors of the Walrus.

“Since we were returning from an overnight trip, we had our sleeping bags and all the gear we needed to spend the night (pillow, comb, toothbrush, change of clothes, jacket, jammies etc.) All of these items were rolled up in our sleeping bags, since backpacks were not a thing yet,” Ancich recalled.

“When we returned to camp, none of us had our sleeping bags, which we used for bedding on our bunks. Word got out that we needed bedding so neighbors near Camp Blanchet donated blankets and sleeping bags to us,” she said.

The lyrics of “The Great Ship Walrus.” It is unclear if these lyrics were written before the boat sank or updated after.

Front page news

Ancich and two other girls were the last to get bedding and were sitting by the fireplace in the Camp Blanchet lodge when the newspaper reporter showed up. That is how they got their picture on the front page of the next day’s Tacoma paper.

In the aftermath of the sinking, the Coast Guard praised the Walrus’ occupants for doing “a fine job of averting disaster” when the ship went down. But Cmdr. Albert G. Jones of Seattle noted that any camp boat carrying paying campers was considered a “vessel for hire,” and that the Walrus lacked the inspections required to operate such a craft, according to news accounts.

Referring to all facilities in the area that ferried campers about, “It would behoove them to see about having the boats inspected and also seeing about getting licensed operators,” Jones said.

Ancich does not recall calling her parents in Seattle to tell them about her brush with disaster. “I’m not even sure they knew about the event until they picked me up from the camp bus at the O’Dea (High School, in Seattle) parking lot at the end of the camp session about three days later,” she said.

“I was one of six kids in my family. It was a different time growing up. My family would not have even thought to come and get me,” she said. “For them, I was in good hands at Camp Blanchet.”

(Never heard of Camp Blanchet on Raft Island? The Catholic Youth Organization operated it from 1950 through 1979. The site is still a camp, but now it’s owned by the Greek Orthodox Church. Learn about what’s new at All Saints Camp and Retreat Center.)