Community Environment Government

Owner of huge Crescent Valley forestland threatens logging, selloff to preserve dream of Canterwood-like development

Unpaved peninsula: The Harbor’s hidden forests and fields

Note: Growing up on the Gig Harbor Peninsula used to entail some familiarity with the woods. If you knew the routes, you could cross the peninsula on trails, sticking to fields and forests (and occasionally crossing a country road). That’s much harder today, yet undeveloped land remains in the Gig Harbor area. How else could black bears surprise us so often? Today, we begin an occasional series of articles that looks at these last undeveloped places — where they are, what owners plan for them, and whether they are likely to be preserved as forest and open space.

A California-based real estate investment company that owns 1,012 acres of forest near Gig Harbor city limits is threatening to log the land and sell it off piecemeal to developers.

An executive of Gaines Investment Trust has stated the company will liquidate its holdings — which form much of the eastern slope of Crescent Valley — if zoning changes Pierce County is considering as part of its Comprehensive Plan update become law.

At issue is the “rural density bonus.” That provision in current zoning allows developers to as much as double the number of dwellings they can build on a rural-zoned parcel, provided they leave at least half the land in open space.

The Pierce County Council is considering eliminating this bonus for the comp plan update, which must be passed into law by the end of 2024.

The 1,000-Acre Wood

The flap over this forest — known locally as 1,000-Acre Wood — highlights starkly differing visions for rural Pierce County land between property owners and developers, on one hand, and elected officials and preservationists on the other.

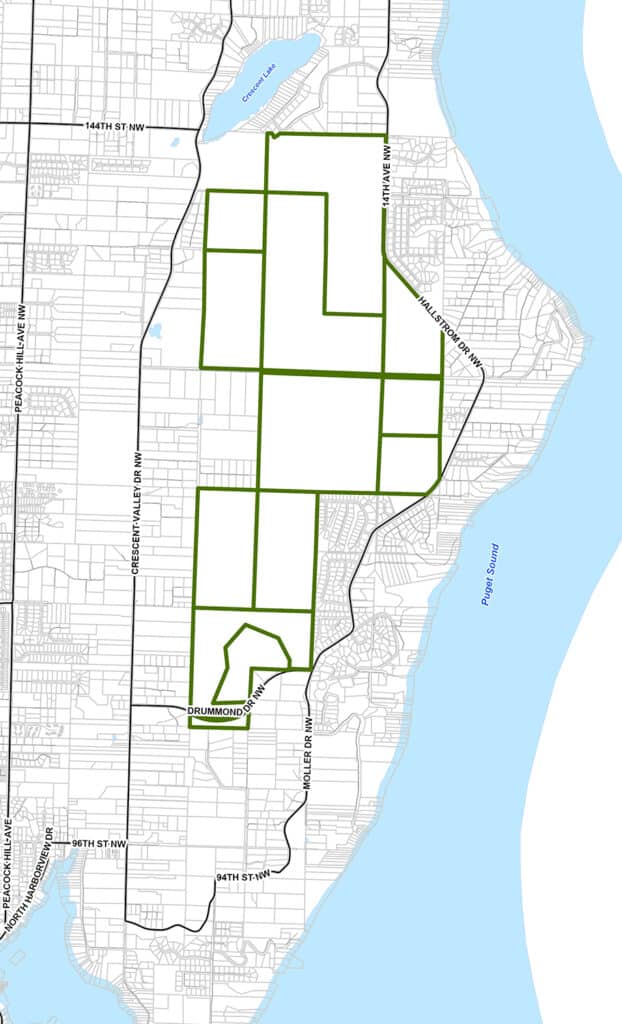

The 1,000-Acre Wood takes up much of the east slope of Crescent Valley, stretching as far north as Crescent Lake to slightly below Drummond Drive in the south. Map created by Tony De Paul, GIS specialist, Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer.

The idea of eliminating the rural density bonus flows from a “High Capacity Transit” vision elaborated by county planners guiding the comp plan update. It is based on “creat(ing) dense neighborhoods within a half mile of bus rapid transit lines” and clamping down on growth outside these areas.

Gaines Investment Trust’s Crescent Valley property is not close to mass transit. But when company officials dream of the forestland’s future, they envision something akin to Canterwood, the luxe 752-acre gated development of million-dollar-plus homes and resort-style living, about a mile west of 1,000-Acre Wood.

“Our dream for the property is and always has been something like Canterwood, with or without a golf course,” reads a comment Gaines executive Gary Bissonette posted in April on a county webpage linked to the comp plan update. “We envision very high-end homes and retirement housing set in a beautiful, wooded setting along with some neighborhood retail to serve the residents of the surrounding area.”

Don Gaines, founder and majority owner of the family-run company, said in an interview that he envisions “probably two- to five-acre lots with as many trees spread around as possible” when the property is developed. A few residences might sit on lots of 100 acres or more. The development might include 50 acres of senior housing, he said.

Rural zoning

That’s a tall order, especially without the rural density bonus. The property lies in unincorporated Pierce County, outside the city of Gig Harbor’s Urban Growth area (UGA). The state’s Growth Management Act concentrates new residences and businesses in cities and in their UGAs. All of 1,000-Acre Wood is designated rural, in zones that permit one dwelling per 10 acres (though this can be boosted to as many as two houses per 10 acres using the rural density bonus). Current zoning does not allow development of new retail.

Along with those zoning challenges, any development at 1,000-Acre Wood would – unlike Canterwood – be far from the Highway 16. Rural roads would struggle to support the traffic generated by a large new community.

To serve the property, Gaines thinks a new road should bisect the land, from Crescent Valley Drive to Hallstrom Drive, so that people on the east side of the valley can connect more easily with amenities like Costco in Gig Harbor North.

How could any of this be accomplished today, with the regulatory tide seemingly against denser development in rural areas?

“As to the future of the Gig Harbor property, and the ‘how to’ deal with zoning and bureaucracy, we don’t have any canned answers,” he said.

A sign on a the Hallstrom Drive NW entrance to the 1,000 Acre Wood property. Photo by Ted Kenney

“The size of the property is important to note; with a property this size, there should be out-of-the-box thinking as to usage when the time comes for development. When that will be is dependent on our assessment of demand for what we envision coupled with what we have on our plate at the time.”

Envisioning an enclave

Gaines said his company wants to build an “enclave of beautiful, environmentally sensitive homes.” Given the size of their land, they “can have a development bigger than Canterwood, bigger lots,” with parts of the resulting community being “like a nature preserve.”

“As to what the trend will be in rural zoning… I have no idea. I think this property needs to be looked at quite differently than any other,” he said.

Many longtime Gig Harbor residents have never heard of 1,000-Acre Wood and would be skeptical that a tract of privately-owned, undeveloped timberland even half that size exists within a 30-minute drive from their pretty-well-built-out city.

But it’s more like a five-minute drive from the old Masonic lodge building at Crescent Creek Park, inside the city’s northern boundary, to a trailhead on Drummond Drive at the southern edge of 1,000-Acre Wood. The property is still a commercial forest, as it was in 1998 when Gaines Investment Trust bought most of the land from timber giant Pope Resources (now Rayonier).

Another gate is on Hallstrom Drive, at the property’s eastern boundary. A sign there declares the land a “Certified Tree Farm” (the most recent logging took place in 2014). To the north, a trailhead on county land near Crescent Lake gives recreationalists access to 1,000-Acre Wood’s network of roads and trails.

Current recreational uses

The forest isn’t a complete secret. The owner allows hiking, bicycling and horse-riding within 1,000-Acre Wood, earning praise from the local community for doing so. Some of the trails have made it into the popular AllTrails.com app and website. The listing for one of them, the 4.3-mile Spadoni and Crescent Lake Loop, describes the surroundings as “a nice forest with varying microclimates, from lush to dense areas.”

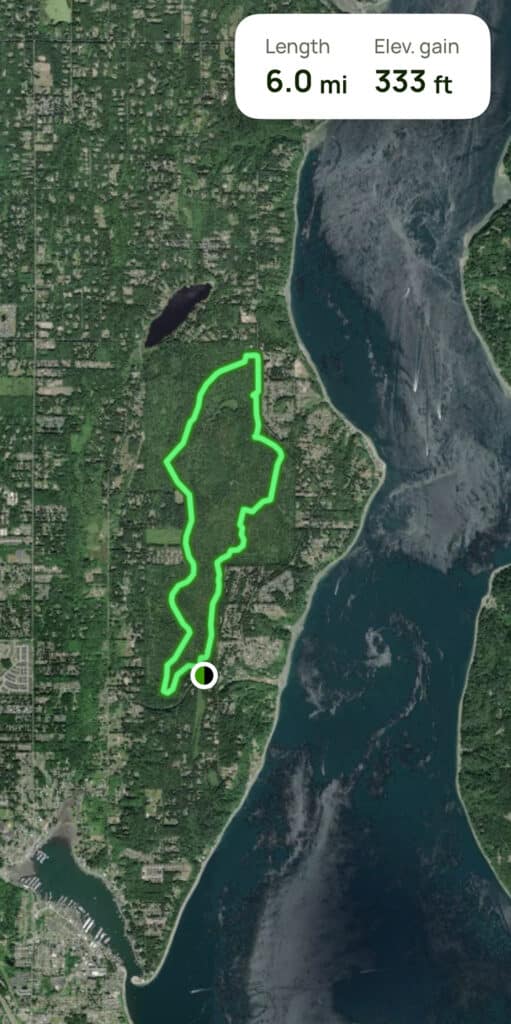

Probably the longest hike in 1,000-Acre Wood is this 6-mile loop starting from a trailhead on Drummond Drive. Photo from AllTrails.com.”

Joe Korbuszewski, a Tacoma-based gravel-biking enthusiast, bike repair entrepreneur and blogger, has visited 1,000-Acre Wood dozens of times. He discovered it in 2019 on Google Maps, where it shows up as an unnamed forested space.

“I know quite a few cyclists who ride there, and there are pretty much always hikers, trail-runners, and dog walkers when I visit, but I’ve also spoken to people that live in Gig Harbor who have no idea what I’m talking about when I mention it,” he said.

“I think that because it’s not a park, and it doesn’t really show up as one, it’s lesser known (given its size) than other places. Unless you drive by one of the entrances, or someone shows it to you, you’d have no idea you could even go in there.”

Bicycling through the 1,000 Acre Wood. Photo by Joe Korbuszewski of Washington Gravel.

Previous threat of legal action

Local environmentalists know 1,000-Acre Wood as a vital part of a prized local ecosystem. The land is not inside the Crescent Valley Biodiversity Management Area (BMA), one of 16 biologically rich areas and connecting corridors singled out by Pierce County for environmental stewardship. But Gaines Investment Trust’s massive patch of forestland, with its tree canopy, understory and scattered wetlands, helps the entire valley to support healthy populations of birds, fish, mammals and other creatures.

An earlier attempt to safeguard 1,000-Acre Wood’s biodiversity through regulation sparked threats from its owner. In 2009, the citizens’ group Crescent Valley Alliance pushed to expand the biodiversity management area boundaries to include the property. The change would have imposed low-impact development (LID) land use techniques on portions of the property not already subject to them.

“We vehemently object to any change that would impair our ability to develop the property pursuant to the zoning that was in effect when we purchased it,” Don Gaines wrote in a letter to the Pierce County Council and county executive at the time.

“If you force me to hire the best land use attorneys – I will. If you force me to fence my property off from people who now enjoy it – I will. If I have to do that I will have every trespasser arrested and prosecuted. No one will set foot on our property without our consent ever again.”

Should the proposed changes move forward, “please be prepared for a lawsuit that will cost the county and the Crescent Valley Alliance more money in legal fees, actual and punitive damages, than anyone ever thought possible,” Gaines wrote in 2009.

County backed down

The county dropped the plan to place 1,000-Acre Wood in the Crescent Valley BMA, said Lucinda Wingard, a Crescent Valley resident and Alliance member.

Wingard said she received a similar letter at the time. She characterized it as threatening a “S.L.A.P.P. suit” or Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation — a lawsuit intended to silence critics by burdening them with legal costs until they abandon their criticism or opposition.

Asked today whether the letter was an overreaction, or an attempt to scare his neighbors away from engaging in the political process, Gaines said: “As I recall, at that time we consulted with local counsel as we do whenever we feel our interests need to be protected. Since then, trees have grown, nature has flourished and people have enjoyed the property. I would say that there couldn’t be a more favorable set of circumstances for our neighbors.”

Fast-forward 15 years and Gaines Investment Trust takes an equally hard line in its statements about potentially losing the rural density bonus.

“If the proposal passes to remove bonus density, that will initiate a drastic change in our plans and attitude for our 1,000 acres,” company exec Bissonette wrote in his public comment in April.

“Our Canterwood dream would be over. We would probably log the asset and sell the land to developers to recoup our lost profits,” he wrote. The company would restrict access “for obvious safety reasons and 1000 acres of nature would be destroyed in a heartbeat.”

Hopes for a park or conservancy sale

Robyn Denson, Pierce County councilmember for Gig Harbor, responded to Bissonette by letter shortly after he made his comment. She attempted to smooth his feathers and broached the idea (often suggested by the preservation-minded) that 1,000-Acre Wood could be acquired and remain undeveloped through transformation into a park or land conservancy.

“Your 1,000 acre property is wonderful and is such a treasure for the community!” Denson wrote. “I know many who really appreciate your generosity in allowing access for walkers, bikers, etc.”

“You laid out very clearly your position and experience as a developer and I don’t for a minute question your capability of developing this site.”

“That being understood, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that if you and your family would ever be interested in selling this property to a group for a park, I know several organizations who would be interested. I mention this as there is a particularly suitable grant opportunity coming up in 2025 (only comes up every other year) that would be able to assist a non-profit in paying assessed value for the property and I know these discussions can take some time,” Denson wrote.

Bissonette didn’t reply to the letter, Denson said. Outreach to the property owner by Great Peninsula Conservancy regarding possible preservation of the 1,012 acres has also gone unanswered, said Erik Steffens, the group’s conservation director.

Don Gaines is not interested in working with preservationists now. “What benefit do we get doing that?” he asked. There will be opportunities to talk about conservation “when the property gets developed,” he said.

Rural density bonus

Gaines Investment Trust is not alone among Gig Harbor landowners and developers hoping the county will keep the rural density bonus. County planners and politicians pushing for its elimination “don’t understand what they’re doing,” said Jim Peschek, a developer working on several projects that rely on the rural density bonus.

Obtaining such a bonus involves mapping the property to identify wetlands, steep slopes and other critical areas. Those are then locked into preservation for perpetuity, Peschek said. He points to one of his projects, The Reserve on Fox Island, as an example of how using this bonus is “actually a better way to protect the environment” than focusing development on 10-acre lots separately.

The Fox Island development groups 12 building lots together. They share a 50-acre parcel with “over 35 acres of dedicated wildlife habitat” that includes stands of Oregon white oak, he said. With the density bonus, “you really have to cluster your (building) lots closer together,” resulting in larger contiguous areas that remain untouched, he said.

Peschek’s company, Gig Harbor-based Bask Enterprises, also built houses at Paddock Wood Farm, which he described as an equestrian-themed community containing 13 building lots on 88 acres on a hill above the Artondale Valley. The rural density bonus enabled the developer and builders to make desirable housing while preserving “stream corridors [and] massive amounts of open space,” he said.

Peschek, who serves on the Gig Harbor Peninsula Land Use Advisory Commission (LUAC), noted that eliminating density also reduces the tax base supporting schools, emergency response, and other public services.

Considering environmental impacts

Asked whether she is for or against keeping the rural density bonus, Councilmember Denson avoided taking a side. “Too much development” is a complaint she hears frequently from Gig Harbor and Key Peninsula residents, and eliminating the rural density bonus would slow down development, she said.

The creation of dedicated open space is a “positive note about rural bonus densities,” Denson said. “However, the county does not have the capacity to monitor whether this open space is actually preserved over time and I have heard from constituents frustrated to see designated open space in their community logged, paved-over, etc.”

Denson noted that the environmental impact of eliminating the rural density bonus is now under consideration by the county’s Department of Planning and Public Works and that “the impact of this proposed change is still being studied by a consultant. I will make my final decision” once all the information is available, this fall.

Thanks to Spencer Bowman of the Tacoma Public Library’s Northwest Room for help researching historical materials for this story.