Community Environment

New data, new progress on Donkey Creek contamination

The slow-rolling saga of Gig Harbor’s attempts to find, measure and cleanse toxic chemicals from its streams and harbor waters is picking up velocity, albeit at a stately pace.

The Washington state Department of Ecology and the Gig Harbor Sportsman’s Club have resumed work on a lead pollution clean-up plan after Ecology named environmental engineer Sam Meng the permanent site manager for the Donkey Creek area. The lack of a permanent site manager stalled work on the plan for years.

Studies dating to the early 2000s attribute alarmingly high levels of lead to ammunition used at the Sportsman’s Club shooting range. Meng expects a final plan by “late 2023 or early 2024.’’

Donkey Creek empties into Gig Harbor near the Harbor History museum.

Meanwhile, the Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife found high levels of lead and even higher doses of PCBs (or polychlorinated biphenyls) in caged native bay mussels implanted in the Donkey Creek delta. The delta is where where fresh creek water meets the salt water of Gig Harbor Bay. WDFW released the data earlier this year.

Upshot: The developments may finally lead to action plans to clean up heavy metals and other toxins that threaten the health of salmon in local streams.

Mussels and PCBs

Fish and Wildlife has conducted every-other-year Mussel Watch studies at some 40 sites around Puget Sound, including Gig Harbor, since 2012.

Results announced this year cover 2019-2020, according to Mariko Langness, Fish and Wildlife biologist and lead author of the new report. That’s the most recent years for which data are available.

Langness said Fish and Wildlife detected high levels of pollutants in each of the four biannual tests at Donkey Creek.

“In Gig Harbor, we continue to see higher concentrations at the Donkey Creek site – at or above the 95th percentile of our monitored sites,’’ she wrote in an email to Gig Harbor Now. Scientists have linked long-lived PCB chemicals to some cancers and reproductive problems in humans since the 1970s.

WDFW uses a site in Hood Canal and another in Penn Cove as its benchmarks for measurements, Langness explained, due to the relatively little development and small populations at those sites.

“When compared to a relatively clean reference site in Hood Canal, Donkey Creek PCB concentrations were three to four times higher,’’ Langness observed.

Lead concentrations also high

Lead concentrations at the Donkey Creek site are at or above the 75th percentile, she said.

“Although this study was not designed to evaluate seafood safety,” Larkness said, “seafood contaminant screening levels provide another reference for comparison to help judge the contaminate levels we report.’’

Mussels from Donkey Creek exceeded health screening levels established by Washington Department of Health, Larkness noted.

A mussel cage at the Donkey Creek delta.

As for lead in mussels — or, for that matter, in salmon — Langness said: “There are no WADOH screening levels for lead, which is considered unsafe at any level of consumption.’’

These high levels of contamination were recorded after just three months of exposure. Wild mussels that inhabit polluted sites year-round would have still-higher levels of toxins, putting people who consume them at risk.

Working those mussels

Harbor WildWatch science director Stena Troyer heads Fish and Wildlife’s Mussel Watch program in Gig Harbor and Port Orchard.

Typically, Troyer and one or two volunteers wade out to the Donkey Creek Delta about 8:30 p.m. in winter darkness and at low tide. There they implant dozens of cultivated mussels inside a protective cage, “so they don’t get buried in mud and don’t get eaten.’’

Troyer and colleagues leave the briny bivalves in place for three months, then go back and retrieve them. A lab conducts a toxicology analysis.

It’s serious scientific work, but fun, too. “After we finish up, we go to the Tides Tavern for drinks,” Troyer said. Recruiting volunteers is “a pretty easy ask.”

Troyer was not surprised by the high readings of heavy metals and toxic PCBs in and near Donkey Creek. Causes include run-off of motor oil, pesticides and other toxins from impermeable paved surfaces. Such run-off can include another toxic chemical: PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons).

Large fish and birds of prey are also at risk from such chemical concoctions. A build-up of toxins can even endanger fearsome apex predators like orcas, Troyer said.

As part of Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife’s Mussel Watch program, mussels are planted in the delta of Donkey Creek. Courtesy Harbor WildWatch Courtesy Harbor WildWatch

Creosote

Surging storm water also carries contaminates.

“The site is fairly industrialized,’’ Troyer said of Donkey Creek and the harbor. “Gig Harbor has a lot of roads, and a marina, and creosote pilings.’’

Creosote pilings are treated wood structures used in the Gig Harbor marina and widely dispersed throughout Washington. They have attracted the attention of state regulators. The state Department of Natural Resources casts a cold eye on creosote. Builders used the wood preservative to treat telephone poles, railroad ties, piers, docks and floats.

“Creosote comprises more than 300 chemicals that, together, are very effective at achieving their intended purpose of preventing decay or insect infestation,” according to a DNR factsheet.

“But chemicals in treated wood — such as those on beaches or old dock pilings — can be harmful and even toxic to marine species. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are the chemicals of most concern.’’

“Studies show that herring eggs exposed to creosote have a high mortality rate. PAHs are known to increase disease and alter growth and reproductive function in English sole. These chemicals affect juvenile salmonids that migrate through contaminated estuaries by reducing their growth and altering immune function. Herring and other affected species are important parts of the food web for salmon, Orca whales and birds.’’

Moreover, the Natural Resources factsheet cautions, “Creosote can also pose a threat to human health through exposure to creosote vapors on a hot day or through direct contact when playing around, sitting on or burning the treated wood.’’

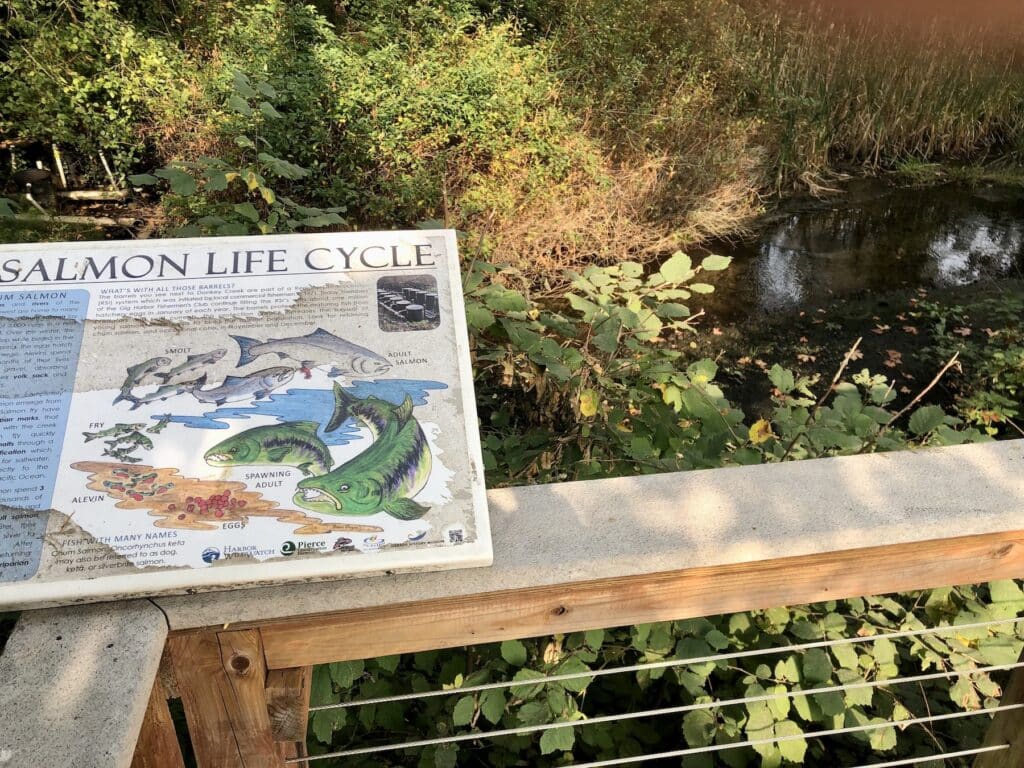

A viewing platform overlooking Donkey Creek at Donkey Creek Park.

Working on a lead plan

Since 2004, the Department of Natural Resources has led a statewide Creosote Removal Program from state-owned aquatic lands. Helping to fund the initiative are, among others, the Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Department of Ecology.

Which brings us back to Ecology’s renewed effort to craft, with the Gig Harbor Sportsman’s Club, a clean-up plan for toxic lead in Gig Harbor creeks and harbor waters.

Ecology’s Meng confirmed that talks with the Sportsman’s Club have resumed.

Meng works with two representatives of the Sportsman’s Club: Mark J. Davis, a Gig Harbor attorney, and Phil Cordell, a senior geologist with Farallon Consulting.

Cordell did not reply to multiple Gig Harbor Now requests for comment.

Davis said he meets regularly with Meng and other Ecology staffers at the Sportsman’s Club property. “We work with anybody they send out,’’ he says. “We’re walking around with them.’’

Davis said he submitted a first-draft remedial study on behalf of the Sportsman’s Club in January. The club is waiting for Ecology’s comments.

A cordial process

Donkey Creek is one of eight sites Meng oversees.

“Currently, we’re still at the remedial investigation stage, where we collect data and information necessary to define the extent of contamination and to characterize the size. The data and information are summarized in a remedial investigation report. The report has just been amended to incorporate additional soil and sediment data collected during 2021 and 2022, and resubmitted to Ecology for review.’’

The Gig Harbor Sportsman’s Club

Meng continues: “I’m conducting my review to determine if the data and information are sufficient so that the site can move to the next-stage feasibility study. The purpose of the feasibility study is to develop and evaluate alternative cleanup actions.’’

Meng estimates a plan could be in place “late this year or early 2024.’’

Davis thinks it could be “a matter of years.’’

Farralon Consulting will have a key role to play in the nitty-gritty of a clean-up, Davis notes. “I’m not an expert on what works and what doesn’t.’’

Regardless, Davis attests, “We’re working with Ecology. We want to make sure it’s done right.’’