Business Community Environment

Neighbors press city about The Reserve, a development planned above Crescent Valley

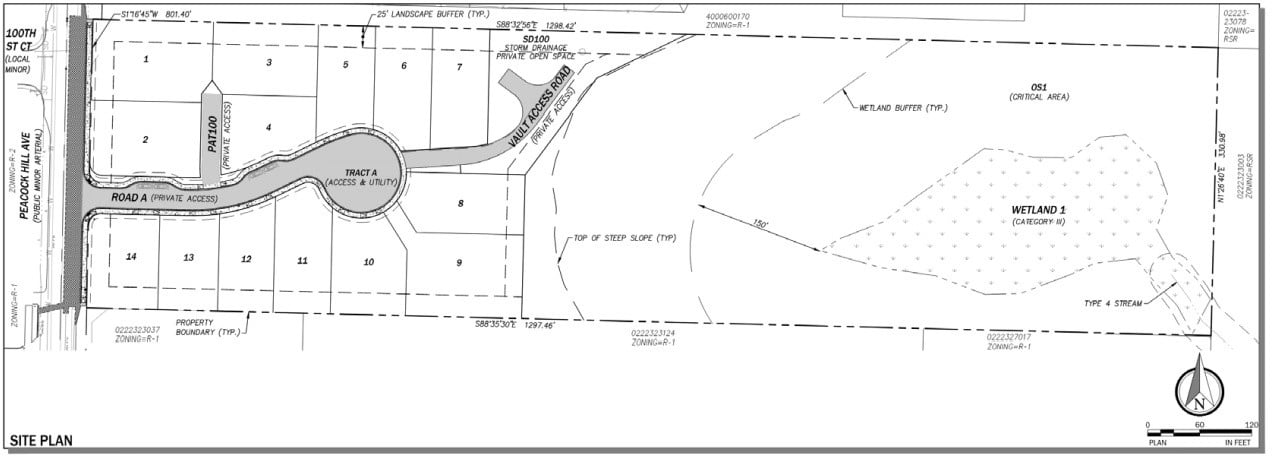

The land slated to become The Reserve, a planned subdivision in Gig Harbor extending from Peacock Hill Avenue eastward down the hill toward Crescent Valley, is hardly a slam-dunk for development.

The long, narrow 9.88-acre site slopes noticeably on its western half, where developers plan to build 14 homes. It then drops sharply to an area with a wetland and stream, making the eastern half undevelopable for housing.

This sign marks the location of The Reserve, a planned 14-home development on Peacock Hill Avenue. Photo by Ted Kenney

Development details

The site will need more than 18,000 cubic yards of fill dirt to level out the topography. Plans call for houses to step down The Reserve’s private road in terraces, each lot shored up by a retaining wall.

Some homes will have daylight basements and others will feature garages tucked under their living space. Both designs attempt to accommodate the slope and tight lot sizes. The city granted The Reserve multiple variances from public works standards, all necessitated by the land’s small size, narrowness and challenging terrain.

“The topography and the grading and the retaining walls” make The Reserve difficult and “really expensive” to create, said Ryan McGowan, owner of RM Homes, the developer.

The 9.88-acre property where 14 homes are planned runs east from Peacock Hill Avenue.

Some neighbors oppose The Reserve

Some neighbors believe those same challenges, along with The Reserve’s location upslope from the pristine Crescent Valley watershed, mean that the subdivision shouldn’t be built at all. These nearby property owners are unhappy that the city of Gig Harbor provided the variances, and that the Gig Harbor Hearing Examiner granted preliminary plat approval last summer, over their objections. (Actually it was a re-approval; the hearing examiner OK’d the same project in 2017, but that approval expired after the previous developer did not move forward within the required time.)

In an added twist, the news broke locally in late summer that in June the state Department of Ecology fined RM Homes $56,000 for construction-related water quality violations at Hillstad, another Gig Harbor project. The DOE said it found 15 separate violations, and only issued the fine after trying to work with the developer over several months to correct the problems.

RM Homes disputes the allegations and appealed the violations and fine.

The city of Gig Harbor knew about DOE’s investigation of Hillstad’s water quality issues before the state levied the fines, and prior to the July 18 hearing examiner session regarding The Reserve. A city inspector reportedly informed Ecology about Hillstad’s water quality problems. The neighbors, however, say they knew nothing about the violations in the period leading up to and including the hearing on The Reserve.

City not allowed to consider violations elsewhere

Could knowledge of the DOE violations at Hillstad have helped neighbors make a better case against The Reserve? Tony DeMarco, who lives in the Scandia Heights development just north of The Reserve’s site, wishes they’d been able to try. He argued that the violations should have dampened the city’s willingness to work with RM Homes.

“It seems the current process is based on the educated opinions of the City Planning staff” and their recommendations to the hearing examiner. He said the city could have moderated what to him appeared to be enthusiasm for the project to move forward.

Location of The Reserve, a 14-home development off Peacock Hill Avenue.

The city said it is not allowed to let an issue like RM Homes’ alleged water-quality violations and $56,000 fine at Hillstad influence its actions affecting the developer’s preliminary plat approval application for The Reserve, or its decisions to grant or withhold variances.

‘Not a special privilege’

“Let me be clear, the city is not ‘working with’ RM Homes to gain approval for the new development,” City Administrator Katrina Knutson said in an email to Gig Harbor Now.

“The city … reviews projects submitted, in the order received, and pursuant to the adopted regulations,” she said. “City staff are reviewing the project to ensure consistency with all municipal, state and federal laws. State and Federal law prohibit the city from refusing to review projects from a legal/valid applicant.”

Ronald Ulmen, Jr. a Gig Harbor-based land use lawyer, noted that a variance is not something a municipality can approve or deny based on how it feels about working with a developer.

“It’s not a special privilege,” he said, but instead is a tool that the city must grant to a developer, if its criteria are met.

Protecting Crescent Creek

It’s easy to dismiss opponents of growth as NIMBYs, but easier to sympathize when immersed in the environment of John McMillan’s backyard.

Just a few minutes north of bustling Anthony’s Restaurant on the Gig Harbor waterfront, McMillan’s 4.2 mostly undeveloped acres are darkly wooded. Walking them feels like being in a rainforest, with an understory of salal, huckleberry and Oregon grape, and a stream that goes on to merge with Crescent Creek less than 1,000 feet away.

A high point on McMillan’s perimeter trail provides a view over the property line and into the ravine at the eastern end of The Reserve. Here a wetland feeds McMillan’s stream, which is home to roughskin newts, long-toed salamanders, Pacific treefrogs and red-legged frogs, as well as the signal crayfish, which is the only crayfish native to Washington state.

A wetlands near The Reserve’s property provides habitat for signal crayfish, the only crayfish native to Washington state. Photo by John McMillan

Crescent Valley’s pristine environment and abundant open space are reasons Pierce County deems it one of 16 Biodiversity Management Areas (BMAs), or “biologically-rich areas and connecting corridors” that should be prioritized for preservation under mechanisms like the county’s Conservation Futures Program. The Crescent Valley Alliance (CVA), authors of a stewardship plan for the area that was adopted into the county’s Comprehensive Plan in 2009, calls Crescent Valley “one of the unique places (in Pierce County) that sustain healthy populations of fish, mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians.”

Annexation and jurisdiction

The Reserve’s site is where this unique habitat and wildlife corridor meet urban growth. In the CVA’s stewardship plan, that land is shown within the Crescent Valley Biodiversity Management Area.

But in 2006, it was annexed to the city of Gig Harbor and placed under single-family residential zoning. Before that, it was in Gig Harbor’s Urban Growth Area, or the area outside the city boundaries designated for future urban growth.

That annexation turned The Reserve’s site into a finger of incorporated Gig Harbor extending eastward from the city’s border along Peacock Hill Avenue, surrounded on three sides by unincorporated Pierce County. That fact isn’t lost on Joe Norberg, a Crescent Valley resident who opposes The Reserve.

A year-round tributary of Crescernt Creek runs through the northeast corner of John McMillan’s property, adjacent to the planned Reserve development. Photo courtesy John McMillan

He believes Gig Harbor officials would be more responsive to opponents of the project if they were also constituents.

“This entire project will be hanging over a pristine ravine that is part of the Crescent Valley Watershed, at the base of which lies Crescent Creek which is a salmon-bearing habitat,” McMillan, a founding member of the Crescent Valley Alliance, wrote in a letter to the hearing examiner opposing The Reserve.

Noting that The Reserve is within the Biodiversity Management Area, he went on to write: “It would be commendable for the city to practice the same good stewardship (as the county) on a municipal level and deny this application as proposed.”

City answers some questions …

In the period leading up to the July 18 hearing, the city responded to some of the neighbors’ concerns. For example, when asked by McMillan in writing: “Who is tasked with monitoring the quality of water coming out of (The Reserve’s stormwater detention) vault and into the ravine?” A city planner responded in writing that “The owner (future Homeowner’s Association) is required to ensure safe and compliant maintenance and operation of the stormwater system per the Stormwater Maintenance Agreement which includes a source control manual and standards for water quality.”

In an email conversation with Gig Harbor Now, City Administrator Knutson further explained that HOAs that own private stormwater facilities are required have an inspection performed once per year by a qualified third party or by city staff. The owners must perform needed maintenance, then report to the city the results of their inspection and provide proof of maintenance.

Failure to follow these steps can result in escalating enforcement including violations and fines of $100 per day.

“In the event of imminent threat to public health, welfare, or water quality, the Stormwater Maintenance Agreement gives the city unrestricted authority to access the stormwater facilities for the purposes of maintenance, repair, and/or retrofit. All costs incurred by the city would need to be reimbursed to the city,” Knutson wrote.

… but neighbors want more answers

Neighbors say their big-picture questions and “what-if” scenarios received scant response.

For example, to handle runoff and prevent discharge of sediments and harmful chemicals, The Reserve will have a complex and expensive stormwater management facility. This will incorporate a large concrete detention vault.

It is designed to store and filter runoff, then release clean water at a rate that mimics the site’s pre-development flow, to prevent outflow from The Reserve from damaging Crescent Creek and its associated streams and wetlands.

The view from a trail on John McMillan’s property into The Reserve property. Photo by Ted Kenney

The project’s Preliminary Drainage Control Plan, available from the city’s planning webpage for The Reserve’s preliminary plat application, explains the technology, but in dense technical language. It does not contain easily discernible answers to questions like: “In an era of increasingly extreme weather, will the stormwater system stand up to a 50-year storm? Or two back-to-back 20-year storms?” and “If a tanker truck of pesticide spills in The Reserve, will the filtration system send out real-time alerts when it has reached capacity?”

When asked these questions and some others, Knutson said city staff are “still reviewing” the Preliminary Drainage Control Plan’s contents. She said CPH Consultants, the Kirkland-based engineering firm that authored the Preliminary Drainage Control Plan, was better-equipped to answer the questions.

CPH Consultants turned down a request to answer questions (including those mentioned above) about the stormwater management in The Reserve. Knutson said Gig Harbor staff are “currently swamped with other priorities” but could answer the questions if given one week from the date they were submitted.

“Of course we desire to transparently communicate with our residents,” she wrote.