Community Environment Health & Wellness

Jennifer Preston: From wanton waste to good taste

When I was young, my family struggled through some tough times and we were on government assistance. I remember standing in line at my mother’s side for yellow bricks of cheese at a government warehouse. I recall accompanying her up and down the grocery store aisles as she painstakingly selected food and household supplies. She thoughtfully considered the size and value of each item and placed the winners in our shopping cart while my oblivious, happy baby brother entertained himself in the cart’s front seat. I was only 6, but somehow knew this was extremely important, though boring, business.

While my mother counted out paper that looked like money, but wasn’t money, I slipped towards the exit to look for change in payphone coin returns or busied myself fiddling with candy dispensers. (What a spectacular day if I found a quarter!) Later I learned what “food stamps” were, why my mother had been extremely selective about what she purchased and how she frugally turned the raw ingredients into delicious, wonderful meals. This early experience taught me several important lessons: to value food, select nutrient dense options and prepare it with little to no waste.

Naturally as an adult, I thought I was good at economizing in the kitchen. Until I traveled overseas. Those trips taught me a lot about waste.

Garden of eatin’

Once I was staying in a remote town and each morning walked to the market on a dirt road lively with dogs and chickens, the trees overhead crawling with massive iguanas. I arrived early because the market sold out of many items — it only took one time going hungry to learn this valuable lesson. Daily essentials, like avocados, garlic, jalapeno and lime, became treasures.

With food in short supply and nine people to feed, I knew how precious our cache was. I’d never scooped an avocado so thoroughly, reamed a lime as effectively, nor minced a single garlic clove so carefully, a size I’d be tempted to throw out at home. Every last scrap was used. The experience made me realize how much we wasted at home. When I returned to the U.S., my outlook and habits changed even more.

Illustration by Jennifer Preston

While our situation required us to take advantage of each edible tidbit so we wouldn’t be hungry, something just as fundamental about being conscientious was happening. Tossing good food because it was a tad overripe, too small to easily chop or had blemishes always made me feel bad, or more precisely, mottainai.

The Japanese word mottainai (pronounced moat-tie-nigh) captures this emotion: A sense of regret when something is wasted without deriving its value (from the words mottai, an air of importance or sanctity, and nai, a lack of something). This word is similar to our proverb, “Waste not, want not,” though the English phrase lacks the association with honoring something sacred.

Let’s cut to the cheese

When food is safe and healthy to eat but thrown in the garbage, it’s called food waste. According to National Geographic, there’s more food in landfills than plastics or paper. In the United States, 130 tons of food are tossed each year. That amounts to about 40% of our edible food destined for the trash. To put that in perspective, Natural Resources Defense Council (NDRC) uses this analogy: “If the United States went grocery shopping, we would leave the store with five bags and drop two in the parking lot. And leave them there.”

In an NPR article, Jean Schwab, a senior analyst in the waste division of the Environmental Protection Agency says: “Food waste is now the No. 1 material that goes into landfills and incinerators.”

Meanwhile, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines not having enough to eat as food insecurity: “A person is food insecure when they lack regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life. This may be due to unavailability of food and/or lack of resources to obtain food.”

Every county in the U.S. experiences food insecurity, and 49 million Americans turned to food banks last year. In Pierce County, almost 100,000 people struggle with this problem, though we regularly dump 40,000 tons of edible food.

Once we address this extravagant waste, we save money, protect our environment and reduce hunger in our communities.

Romaine calm

A stunning 83% of food waste occurs at home and in restaurants. Though some chefs are thoughtful about their ingredients and how to use them efficiently, restaurants still squander tons of food.

How does this happen? Leftovers on the plate and in the kitchen, food rejected by customers and prep work wastefulness – are all thrown out at the end of the day, destined for landfills.

We’ve all experienced being too full to finish a meal and many are familiar with food chains that boast 12 laminated pages of colorful menu photos and dozens of options (most of which taste alike). The more options available, the more ingredients the restaurant must have on hand, which can translate to food waste.

For a quick fix, restaurants can offer smaller portions, provide fewer menu options, conserve more food during prep, divert extra to food banks and compost.

Jonathan Bloom, journalist and author of American Wasteland says, “There’s about a half-pound of food waste created per meal served.” On his website and in his talks, he emphasizes sharing our “agricultural abundance” by rescuing unused food from restaurants and supermarkets for homeless shelters, and through gleaning, which is the practice of gathering crops left after harvest rather than plow them under.

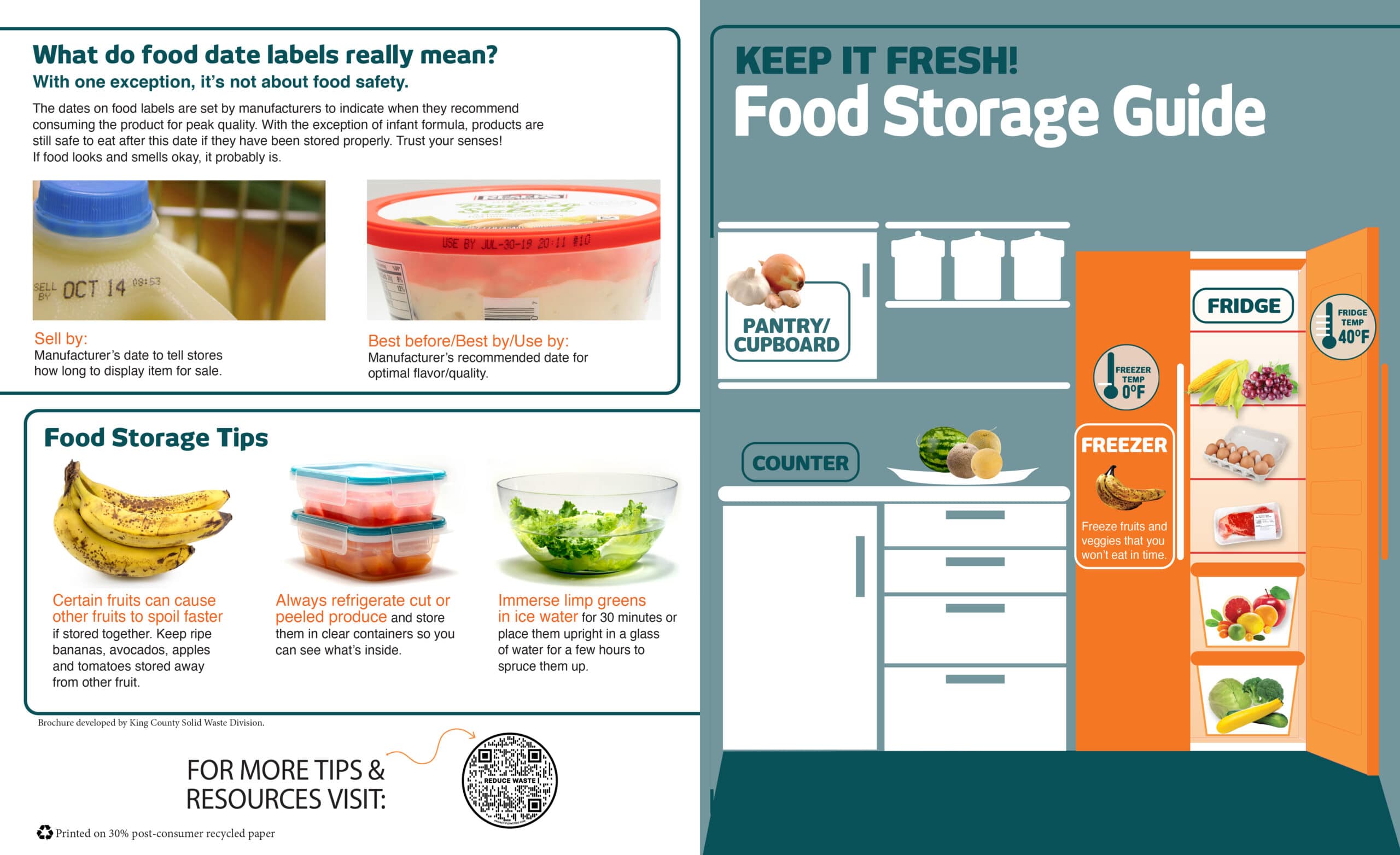

I’m betting many readers have reclaimed good food and “gleaned” in other ways without even knowing it. For instance, I regularly search out deep discounts at supermarkets because an item’s “Sell by” date is close. I collect apples, pears and plums from abandoned orchards and sidewalks, forage for edible mushrooms, berries and “weeds.” I’m betting most of you have stained your fingers purple plucking blackberries each August! It’s fun and feels good, right?

For a closer, behind-the-scenes look at our agricultural abundance and squander, watch Just Eat It, a compelling, award-winning documentary Bloom was featured in that reveals the problem and provides solutions.

High on the hog

The way we produce food is the number one cause of biodiversity loss. And in case we were in doubt, a United Nations report reveals how integral biodiversity is to our survival — responsible for our food, soil, water, weather, and each breath we take. We’re literally eating ourselves to death.

As we churn out food that ends up in the garbage, additional hidden costs continue to climb. There are the products used to create it: water, fertilizer, pesticides. And deliver it: packaging, transport and fuel. On top of this, edible food now rotting in landfills is producing methane, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change and is 80 times more harmful than carbon dioxide because of its capacity to trap heat.

A report by One Planet Network, a global community of policymakers, experts, governments, businesses and international organizations, says that if we continue on this path, and if the population reaches 9.6 billion as projected in 2050, we will need the equivalent of almost three Earth-sized planets to provide the natural resources needed to maintain our current lifestyle.

So, why is this happening when production is so costly and millions of people start or end their day hungry?

Culture. Our culture does not encourage food conservation or resourcefulness. Instead it makes being wasteful difficult to resist.

Here are a few key drivers behind food waste—

- Unfortunately, abundance alters our mindset and influences us to not value food because we have so much of it.

- Blemished food is passed over, much of it thrown away by growers before it even reaches the supermarket. According to Science Direct, “Consumers primarily judge fruit quality based on appearance, and even a moderate amount of bruising can reduce consumer acceptance.”

- Low cost. Food is cheap in much of the developed world, sending the subconscious message that it lacks worth.

- Knowledge deficit. Many of us have not been taught how to properly store and maximize food use.

This is a big problem with an easy fix. It requires a paradigm shift and it begins with us, on the individual level.

Humble ingredients, delicious results

Some restaurants are leading the way with innovative ideas. For example, Chef Dan Barber’s pop-up restaurant, WastED, which debuted in March 2015 for three weeks at his Blue Hill Restaurant in Greenwich Village, New York. The challenge: transform what others throw out into delicious, gourmet dishes at $15 a plate. He successfully showed how to create meals made from scraps and completed the frugal vibe with cozy table arrangements using leafy turnip tops in water dishes and candles made from beef tallow.

Barber is a graduate of the French Culinary Institute and author of the book Third Plate: Field Notes on the Future of Food. He owns Blue Hill in Manhattan and Blue Hill at Stone Barns in Pocantico Hills, New York. He proves that this venture isn’t about suffering and doing without. It’s about having fun, being resourceful and creative.

Upcycled food, or products made with ingredients that otherwise might have been thrown away, is beginning to appear on grocery store shelves. Photo by Jennifer Preston

Catalysts of creativity

Many famous recipes came about as home cooks and chefs discovered creative ways to use leftovers, like turning stale bread into panzanella, old rooster into coq au vin or scraps into paella, traced to the royal banquets of Moor kings, where clever servers brought home leftovers and mixed them up with rice.

I’ve love to see local restaurants experiment with creative solutions for food waste. Here are some of ideas for our communitt:

- Have a friendly cook off using only edible food that would have been thrown out

- Introduce a single menu item using food waste or host a food waste night

- Reduce the number of menu offerings

- Reduce portion sizes

- Remove the Kids’ Menu rule “For 12 and under only” and allow adults to order from it

- Create a “Light Appetite” menu

- Deliver extra food to food banks

- Only serve in-season foods

You butter believe it

You may be wondering how we dealt with food waste in the past. First, we’ve never had such a surplus! The way food is produced today and the global economy has given us more options than ever. Food is constantly grown all over the country and world, transported across oceans and delivered at our feet.

They also ate seasonally — what was available at the moment. No bananas in January. Or in Washington, ever. Do we stop to consider the luxury of eating pineapple in the winter here?

Secondly, people used to live in smaller towns and villages without electrical appliances. They had root cellars, canned and creative ways to preserve meats, but without refrigeration, most food quickly spoiled. This meant they shopped throughout the week for fresh and locally sourced food. We have the The Gig Harbor Farmer’s Market from 1 to 6 p.m. Thursdays through Sept. 14 at Skansie Brothers Park. Among handmade jewelry, household décor, and local business booths, you can find a few vendors with local produce available.

Lastly, eating in restaurants is relatively new for human civilization, becoming popular in the mid-20th century for middle class citizens. Now, sit-down dining is ubiquitous, offering every type of food imaginable, while the fast-food industry continues to grow, fueled by our hyper-busy North American lifestyle.

Lettuce rejoice

The change required may sound daunting, but when individuals take small steps, a culture shift occurs. And then it spreads. As consumers, we direct the market and lead the way with our shopping and eating habits.

Values and perceptions are constantly changing. In the 1960s, sliced white bread was a sign of affluence. Now, we don’t give it a second thought, or more likely, we avoid it all together.

As Chef Barber of wastED points out, 70 years ago lobster was considered trash food and fed to prisoners. A law was passed forbidding lobster meat to be served to prisoners more than once a week, because it was considered inhumane!

We don’t just have to look at history to realize we have options. Different cultures today practice alternative habits. For example, many Europeans have smaller fridges and freezers because they shop more often, buying fresh ingredients. This single routine produces a lot less waste.

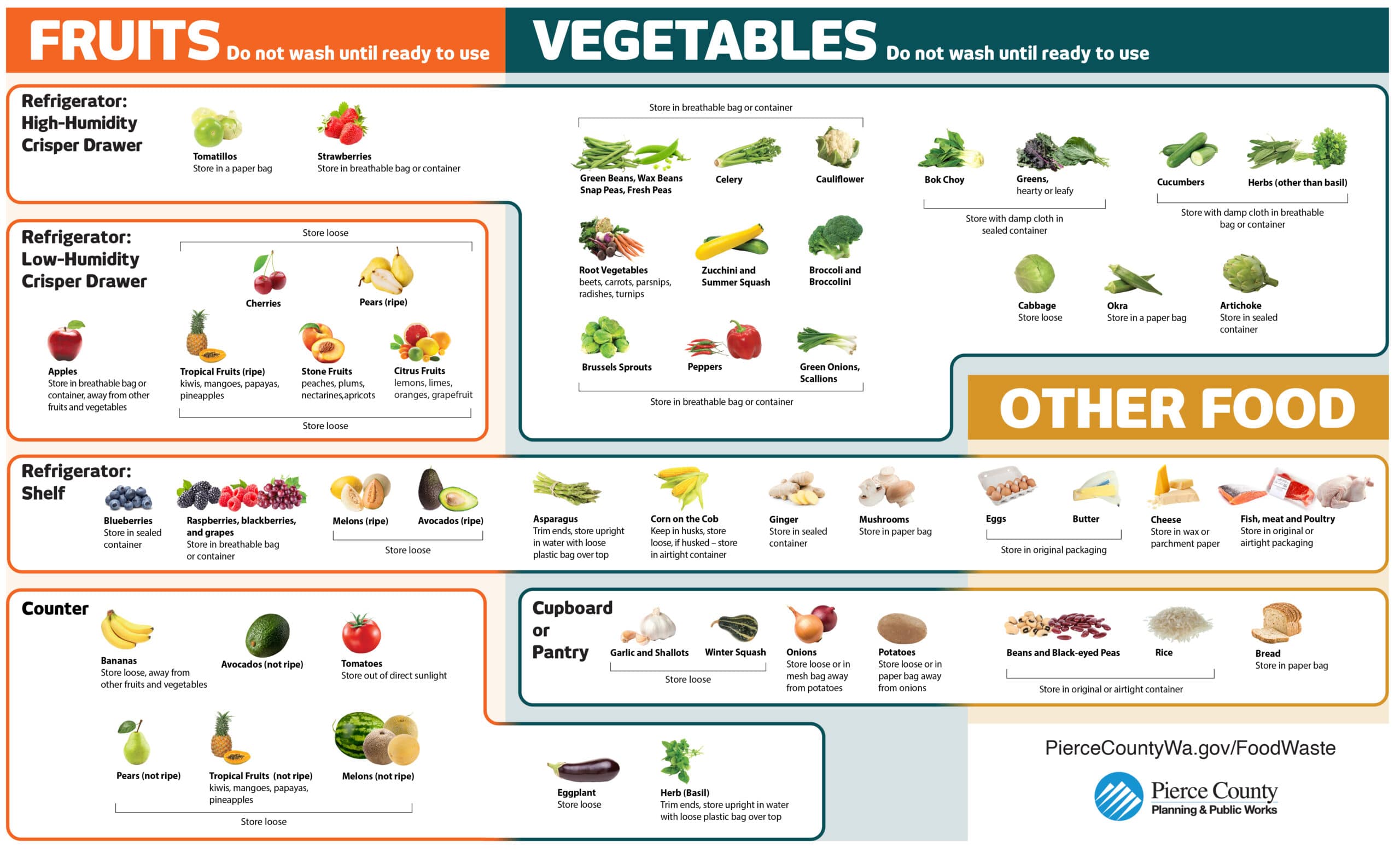

Pierce County Planning and Public Works

Beyond banana bread

Proper storage is key to less food waste. Those plastic bags from the grocer trap ethylene gas, which hastens decay for some fruit and veggies. (See the infographic for more details.) Even with perfect storage, food still ages and the fridge fills with Tupperware.

People have been salvaging food and reinventing it for a long time. Now called “Upcycled Food” by manufacturers, the products are made with ingredients that would have otherwise ended up in landfills. These items are finding their way into supermarkets, from blemished bananas turned into banana chips to rescued grains that add nutrients and flavor to bread.

Kroger Co.’s Simple Truth brand just partnered with UP Inc. in Berkeley, CA. to offer upcycled multigrain breads. They’re being rolled out in a limited number of Fred Meyers and Gig Harbor’s location is one of them. The timing is ripe since 57% of shoppers say they intend to buy more upcycled food, according to UP Inc founder Dan Kurzrock.

Pierce County Planning and Public Works

Leek the news

September 29th is the International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste (IDAFLW). It’s a clunky phrase with a simple message. Acknowledging food waste and changing habits result in reduced air pollution, shipping, packaging, traffic, methane, pesticides and less reliance on foreign products. It encourages eating seasonally and locally, which supports nearby farms, and helps keep natural habitats intact, which supports biodiversity. Which in turn, supports humans.

My next article will discuss how to refocus on food frugality and offer creative tips to reduce and reuse leftovers.

Local food banks

Gig Harbor Peninsula FISH Food Bank

4425 Burnham Drive, Gig Harbor, WA 98332

Phone: 253-858-6179

Key Peninsula Community Services- Food Bank Program

17015 9th Street Court KP North, Lakebay, WA 98349

Phone: 253-884-4440

9127 154th Ave Ct NW Lakebay, WA 98349

(253) 857-7401

621 Tacoma Avenue South, Tacoma, WA 98402

Phone: 253-627-1186

2610 Sunset Drive West, University Place, WA 98466

Phone: 253-460-3134

Jennifer Preston Chushcoff of Gig Harbor is a writer, designer, former Master Gardener and self-described “eco-advocate.”