Community Education Environment Photo galleries

Photos: Low-tide walk at Tacoma DeMolay Sandspit Nature Preserve

On the way to Fox Island’s Tacoma DeMolay Sandspit Nature Preserve on April 1, the weather decided, in appropriate Pacific Northwest style, to fool this reporter.

When I left my house, it was raining and overcast, so, of course, I failed to bring either sunscreen or a hat. By the time I got to the nature preserve to join the low tide walk with Harbor WildWatch’s Rachel Easton and Liz Racine, it was very sunny indeed.

Fortunately, the sun hardly proved a deterrent, either to learning or fun that day.

Easton, Racine, all three reporters — a couple journalists from the Tacoma News Tribune also showed up — and Sarah and Wes (the mother and son who came to the low tide walk) “ooo”-ed and “aaah”-ed over the fascinating, beautiful, and fragile wildlife in the waters around us.

The low tide walk was one of several that Harbor WildWatch will hold over the next several weeks. The walks allow attendees to explore aquatic life in different tidal zones exposed at low tide. Interested attendees can keep an eye on the organization’s Facebook events.

Now, I could tell you whom we saw, and what we did … but I am a photographer, not just a writer, and I happen to prefer to let nature (okay, and some captions) do the talking. So, without further ado: Enjoy this photo essay!

Little enclosed anemones pepper the beach of Fox Island’s Tacoma DeMolay Sandspit Nature Preserve. The anemones fold in on themselves at low tide, and will often pull in bits of broken shells for protection. When the water rises again, they will once again “bloom.” Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Wes, left, and Harbor WildWatch’s operations coordinator, Liz Racine, right, check out some barnacles attach to a rock. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

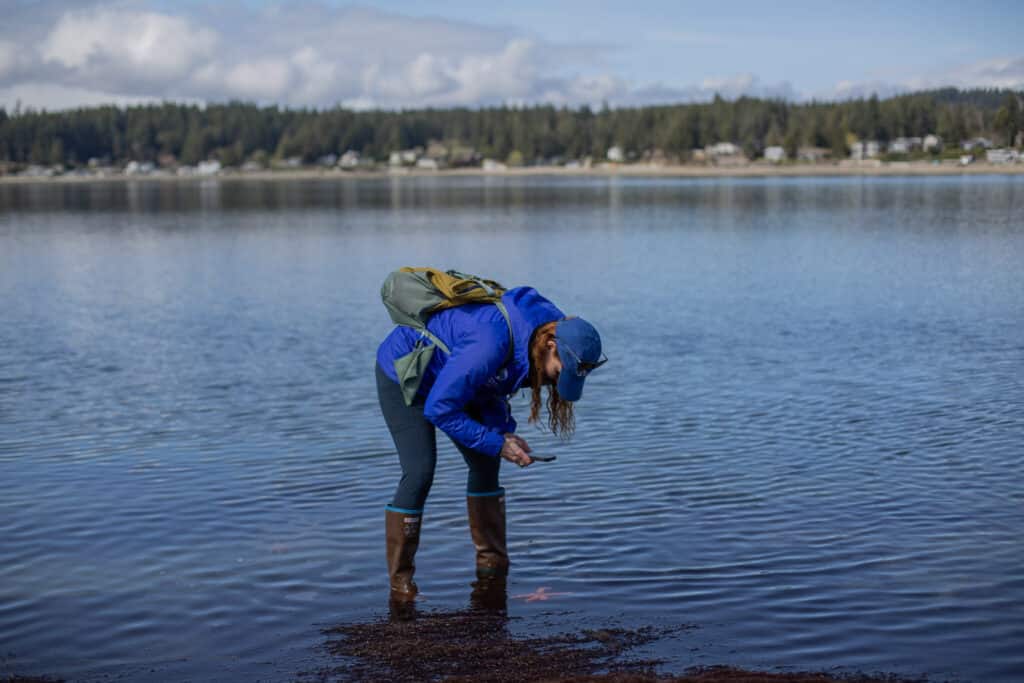

Harbor WildWatch’s education director, Rachel Easton, demonstrates what happens when you bother a horse clam. (Don’t worry, it’s just seawater!) Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

A leather star lies on the wet sand, arms aligned with the water flow lines in the sand around him. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Wes’s shadow is visible on the wet sand of the nature preserve. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Racine holds up a female red rock crab, who is at least as big as her hand. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Racine holds out a sand dollar who is on his way out of this life. He still appears to have spiny little hairs, which will quickly fall away, when he is fully dead. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Racine holds up a leather star. Leather stars have a different texture to their skin than many other sea stars, hence their name. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Wes, right, sniffs the leather star Racine, left, holds out. Racine has just gently rubbed the surface of the star to induce his chemical defense response, which reads to human noses as a black garlic-like odor. The leather star’s chemical defense, rather than a mechanical defense, may be part of the reason leather stars have not been as badly impacted by sea star wasting disease. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

A few leather stars rest beneath the water. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

The tide at the Tacoma DeMolay Sandspit Nature Preserve recedes under a blue sky brushed with clouds. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Sea stars rest amidst kelp in the water. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton demonstrates how a mottle sea star will attach his many little tube feet via tiny suckers to her finger, in order to understand what it is. In addition to their sensory functions, sea stars also use these feet to move and eat. “They remind me of vermicelli noodles,” Easton remarked. “You’ll never eat noodles the same.” Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton takes a picture of the mottled sea star. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Eason holds up a piece of sugar kelp. The kelp is unique in that they have the saccharin molecule, making them a tasty treat for deer and other creatures who have the taste buds to detect sugar. While the kelp is not sugar-sweet, they do have a mildly sweet-umami flavor. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton points out a small hitchhiker known as a scale worm on a pink sea star (whom she calls a “Patrick star,” an homage to the iconic pink sea star character, Patrick, in the long-running children’s television show, “Spongebob Squarepants.”). The relationship between sea stars and scale worms is a commensal one, meaning one party benefits, while the other is neither harmed nor helped. The scale worm gets transportation, protection, room and board, hopping off the sea star and eat whatever the sea star eats. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton holds up a mature northern kelp crab who has lost his right arm. She explained that he is in the process of growing another one in its place. He can regrow missing limbs with any molt — or shell-shedding — as many as he has in his lifetime. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton shows off a long, glorious piece of her favorite kind of kelp, seersucker kelp. The kelp is named for its close resemblance to the fabric of the same name. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton demonstrates the relatively elastic nature of the seaweed colloquially known in English as Turkish towel kelp, so called due to the bumpy surface. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton makes a TikTok video of a graceful decorator crab she has spotted in the water. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton releases the graceful decorator crab back into the water. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

The stealthy graceful decorator crab hides in plain sight. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton demonstrates how stretchy and elastic nori is. This seaweed is the kind we eat in restaurants, she explained. The red seaweed loses their red color when smoked for eating. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Tube worms can be seen sticking out of the sand at low tide. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

A local digs up shellfish for some good eatin’. Later, on the way back up from the beach, he told this reporter that he recently moved back from South Carolina. He was born and raised here, and remembers hunting for shellfish when he was a child. While it is immediately unclear whether he ended up making the chowder he mentioned, this reporter is certain he enjoyed his catch. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

Easton carefully digs a striped nudibranch out of the sand. A 2019 Washington Department of Ecology post about striped nudibranches notes that they are “ferocious” and “[strike] fear into the hearts of tiny invertebrates everywhere!” Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.

The ferocious striped nudibranch pops out his little rhinophores — those are the little antennae-like apparatuses on the top of his wee head — as he makes his way through the water. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick.