Community Education

Peninsula School District embracing potential of ChatGPT

Kara Beloate, an English teacher at Peninsula High School, isn’t banning her students from using ChatGPT as part of their school work. She’s encouraging it.

Education Sponsor

Education stories are made possible in part by Tacoma Community College, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Released in November by OpenAI, ChatGPT is an artificial intelligence chatbot that has creating a buzz for its uncanny ability to engage in dialog and to create original written content from user prompts. ChatGPT is currently free and easy for anyone with a cellphone to access.

What could possibly go wrong?

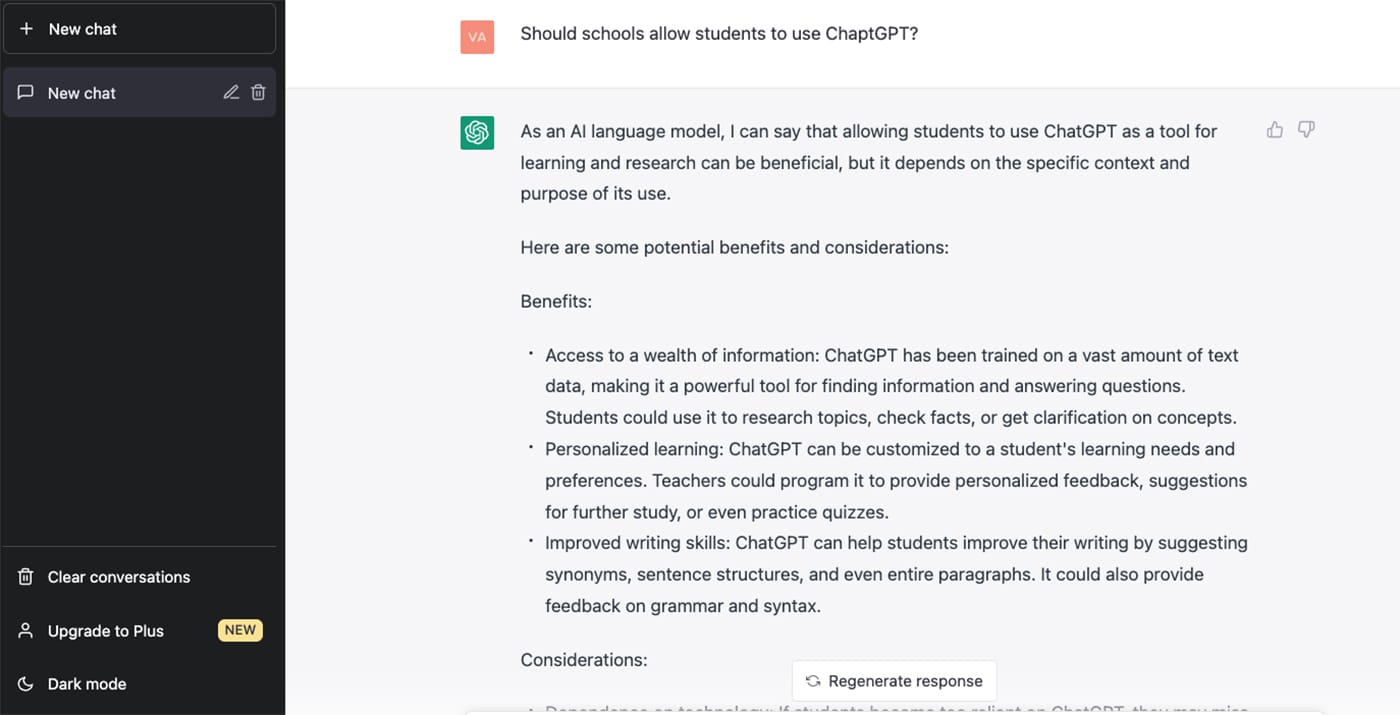

ChatGPT answers questions in a “conversational way,” according to maker OpenAI. Some have raised concerns that students could use the software to cheat on essays or school assignments.

Ban or embrace?

Educators everywhere are grappling with the new technology, wondering if they should ban it or embrace it.

Banning ChatGPT at school won’t stop students from accessing it, Peninsula School District officials figured. So the district has decided to allow the new AI tool in classrooms with age-appropriate access and supervision.

“We believe that the best way to experience the technologies available to students is to do so under guidance from caring adults,” said Kris Hagel, the district’s executive director of digital learning. “And we feel that our teachers are wonderfully suited to be those people.”

‘We can’t hide from it’

ChatGPT is not a one-off; it’s part of a suite of OpenAI language models programmed to produce human-like text. Google, Microsoft and other entities are developing their own.

Peninsula School District was already working on policies for integrating AI into its curriculum when the advent of ChatGPT lit a fire under that effort.

“One of our strategic plan goals is around innovation,” he said. “And while this may be new and scary, we can’t hide from it and must figure out how we will adapt to these new realities.”

Peninsula is training teachers on how they can use ChatGPT to save time on mundane tasks and to create custom learning tools. For example, they could ask it to explain salmon migration using vocabulary for a specific reading level or language.

Since January, staff from the district’s Department of Learning and Innovation have visited classrooms to co-teach lessons on AI at multiple grade levels. High school seniors have been studying Chat GPT to learn how AI acquires human language, how to spot AI-generated misinformation, how to identify “deep fakes” online and how to use AI for beneficial purposes.

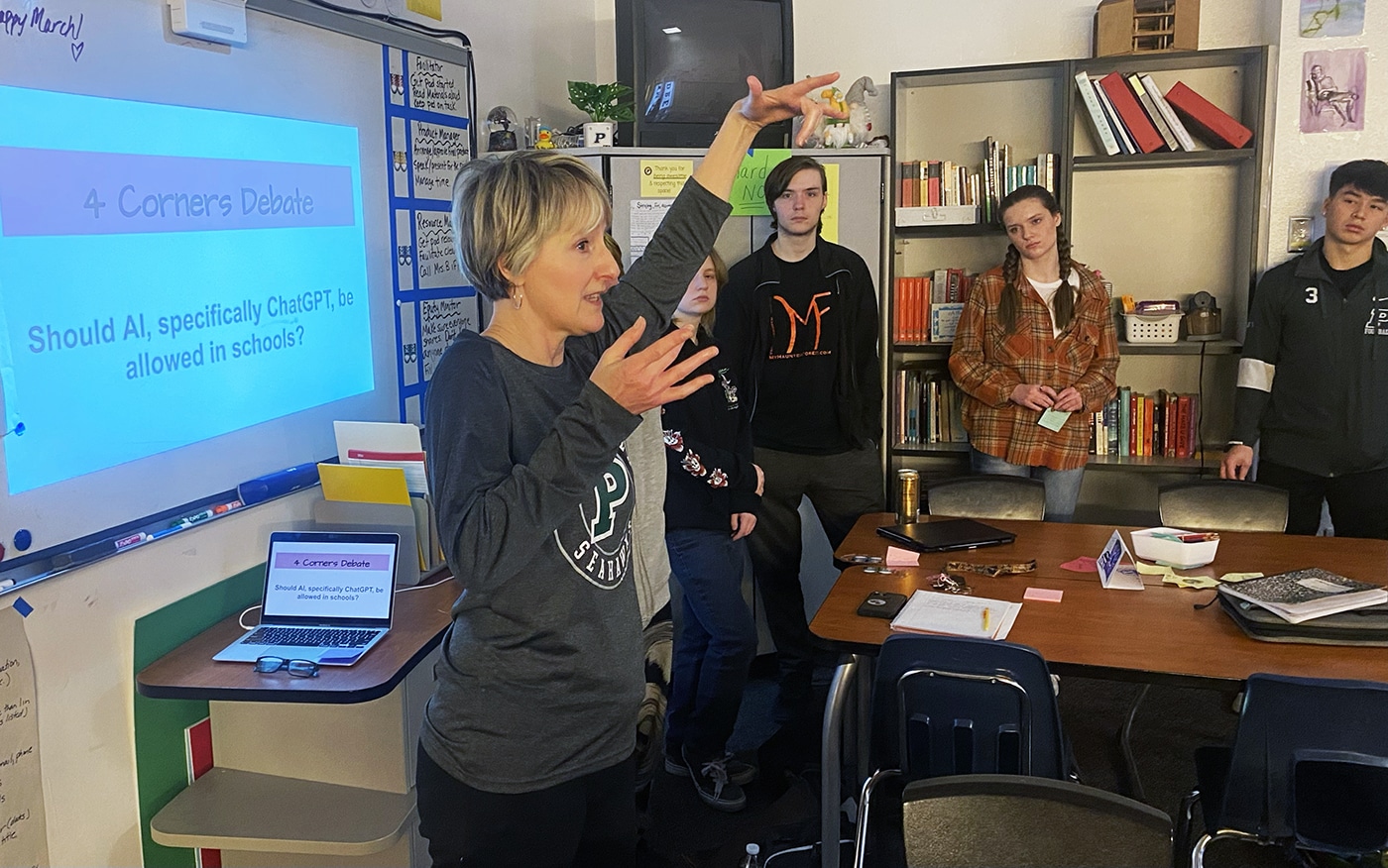

Peninsula High School English teacher Kara Beloate is teaching her students a unit on artificial intelligence and the chatbot ChatGPT. The unit is part of Peninsula School District’s digital literacy instruction. The district has decided it will allow ChatGPT in classrooms with age-appropriate access and supervision.

What other districts are doing

AI has been a hot topic among regional technology leaders in K-12 schools, Hagel said.

“Some districts, like ours, have realized it is here to stay, embraced it, and started adjusting to the changes necessary and finding ways to benefit from it,” he said. “Others are taking a more cautious approach by allowing it for staff but not students. And there are a couple of districts that have blocked it all together and will deal with it later.”

Nationally, the response has been similar.

Hagel believes advances in artificial intelligence will drive change in many sectors of society “at rates we’ve never experienced before.” The transformative power of these technologies is on par with the advent of the World Wide Web and smart phones, he said.

“There will be drastic shifts in entire industries, and our students need to be prepared for what the workforce looks like when they leave our schools,” Hagel said. “Giving them this experience now will give them a leg up on students in other districts who don’t have these experiences.”

About the technology

The “GPT” in Chat GPT stands for “generative pretrained transformer,” a technology which combines machine learning with access to vast data sets of written language.

ChatGPT is fine-tuned with “reinforcement learning from human feedback,” complex programming in which, simply put, human trainers rank responses and create rewards. The result is a platform that can generate all sorts of written content, from computer code to fairy tales.

It can interact in a conversational way, answer follow-up questions, admit its mistakes and challenge incorrect premises, according to OpenIA. But, the company admits, it has its limitations.

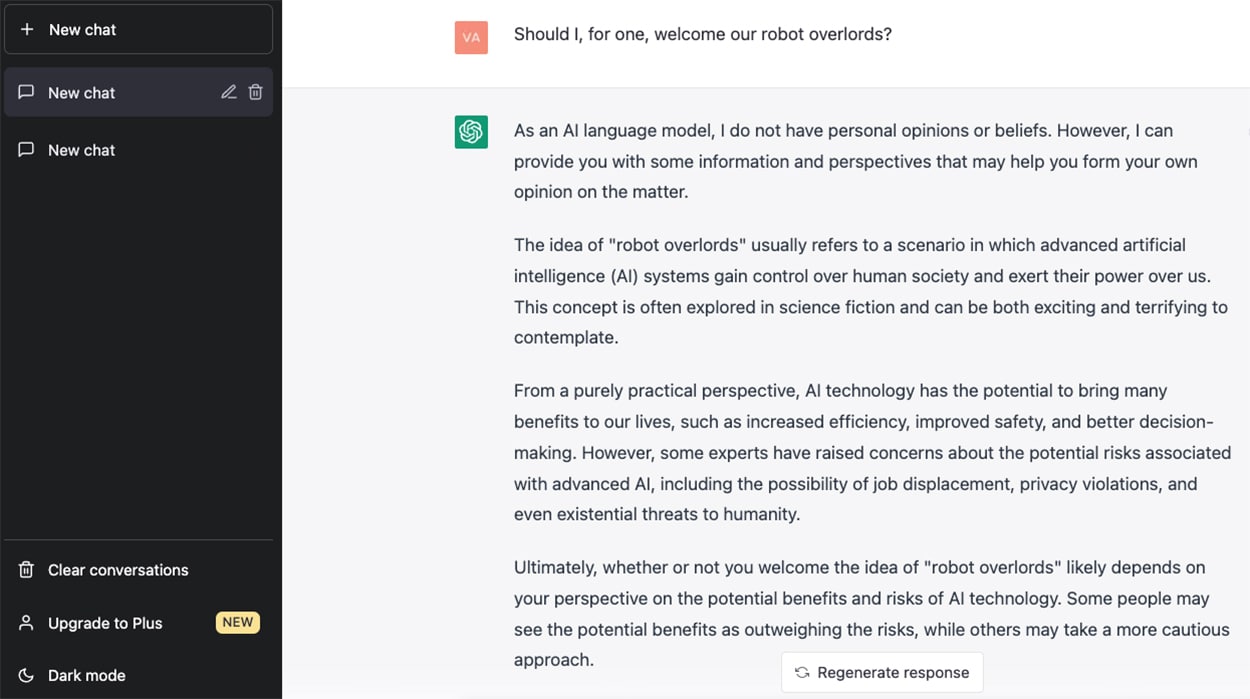

A sample of ChatGPT

ChatGPT sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers, developers say in a blog on the new product. “The model is often excessively verbose and overuses certain phrases.” … and … “While we’ve made efforts to make the model refuse inappropriate requests, it will sometimes respond to harmful instructions or exhibit biased behavior.”

Beloate’s class is piloting an AI literacy unit developed by the district’s digital specialists. But some of her students are already acquainted with ChatGPT.

What students say

“I’ve just started using it,” said Hayden Holt, a senior who has his own personal account outside of school. “I use it for a lot of my speeches and essays I have to write. So, I get it as a baseline for what I’m doing, and I can just go through and revise and edit.”

Justin Duckworth, also a senior, says it helps him with writer’s block and brainstorming creative projects like scripts and songs. Like Holt, he uses it as a time-saver, taking the roughed-out content and putting his own vocabulary and style on it.

“It’s very formulaic and kind of bland, like, there’s no emotion behind it,” Duckworth said. “It’s more of a tool to help me, like an assistant.”

Do some students use it to cheat?

“A hundred percent,” said Holt. “I mean, I know plenty of people have done it. And it turns out they typically don’t get A’s because it doesn’t have that human authenticity. But they get away with it.”

Both students say Peninsula School District is doing the right thing educating students on digital literacy and AI. “I think it’s definitely very progressive, and I do appreciate it,” Holt said.

Brayden Smith takes part in a debate over whether ChatGPT should be allowed in schools during Kara Beloate’s English class on Monday, March 6, 2023.

Both students will continue to use ChatGPT to generate content, but they’ll do their own fact-checking given its unreliable accuracy. Duckworth is wary about the long-term outcome.

“AI is very prone to spreading misinformation, because it cannot tell what is true or not,” he said. “I would try and put a cap on how intelligent we make artificial intelligence because I feel like it would get to a point where it would become, I want to say, too smart.”

Debating AI in the classroom

Recently, Beloate had students debate the value and dangers of AI. “Will AI do more harm than good for humanity?” she asked, telling students to stand in different corners of the room based on whether they strongly agreed, disagreed or fell somewhere in between.

In follow up, she asked if schools should allow AI tools like ChatGPT. One student said yes, but not for younger students. “You wouldn’t give a first-grader a calculator to solve problems,” he said.

Another student, Faye Stock, opposes the idea, saying it would lead people to depend on machines “instead of teaching us that we have to work for what we want to get.”

Uncharted territory for teachers

Donna Squires, a digital learning coach, says most teachers in the district are open to incorporating AI into their own routines and, as age appropriate, into the classroom.

“I think they’re hungry for information,” she said.

For Beloate, “it feels challenging. It feels exciting. It feels scary. I think it changes the role of the teacher because we have to teach kids how to think differently.”

That means more higher-level, critical thinking.

“I’ve been on the bandwagon that education has not made enough advances,” she said. “I think as teachers, it’s our job to keep up with technology and teach kids how to use it in responsible, ethical ways. And if we don’t teach them, who’s going to?”

Peninsula High School student Faye Stock takes part in a debate over whether the AI chatbot ChatGPT should be allowed in schools, during Kara Beloate’s English class on Monday, March 6, 2023. Stock disagrees, saying it will make people too dependent on machines.

The district’s digital learning team has been developing its plan for bringing AI to the classroom with the help of the International Society for Technology in Education. But with AI technology evolving at breakneck speed, the plan is more of a fluid work in progress, Squires said.

“I’m not going to pretend we know everything about it, because we don’t,” she said. “I don’t know where it’s going to go, honestly.”