Community Education

‘Digital citizenship’ a key part of the curriculum at Peninsula schools

Time was, the job of an IT director was all about making sure students had enough devices and that everyone could get online.

These days, Kris Hagel, director of digital learning at Peninsula School District, spends his time supporting teachers instructing students about “digital citizenship,” informing parents of ways to monitor and evaluate their child’s screen time, and worrying about cybersecurity attacks on student and staff data.

The digital landscape is changing rapidly in an age of misinformation, disinformation and outright malinformation, gradients that range from inadvertent sharing of erroneous material to outright targeting of individuals or organizations. Hagel, in a recent report to the school board, cited the Russian campaign to spread lies about its invasion of Ukraine as an example of the instability of information on the internet.

And yet, the digital world remains a trove of resources for education, research, innovation and, yes, social connections that students hold so dear.

Efforts to advance digital citizenship are not new, but Hagel said they have never been more pressing.

“For years, we’ve talked about kids being digital natives,” he said. “They can pick up a phone. They understand how it works. They can push buttons. But do they really understand what they’re doing and the consequences of some of those things that they’re doing?”

“Digital citizenship” — which can apply to everything from fighting misinformation to cybersecurity to artificial intelligence — is an increasingly critical topic in Peninsula School District and other schools.

Standards for educational technology

Since 2018, K-12 districts in Washington state have subscribed to educational technology learning standards that call for schools to “integrate technology literacy and fluency” in their curriculum.

Peninsula, like many districts, borrows from curricula developed by the nonprofit Common Sense Media, best known as a tool for parents with its reviews of movies and video games.

Hagel described a second-grade teacher’s recent lesson in which students learned about their digital footprint.

Student Annalis Parker, speaking at the March 24 board meeting where Hagel made his pitch, talked about high school classes in which teachers introduced concepts about misinformation.

“We actually did a unit in English about fake news,” said Parker, who is ASB president of Peninsula High School and a student representative to the board. “And we watched TED talks on how to recognize this.”

In civics, they watched “The Social Dilemma,” a Netflix documentary about the human impact of social networking.

Parker said she recognizes the importance of “staying educated.”

“So, I just appreciate what the schools are doing to help us learn,” she said.

Six focus areas of digital citizenship

Common Sense Media identifies six focus areas in its lesson plans, adaptable for students in kindergarten through high school: media balance and wellbeing (aka screen time); digital footprint and online identity; digital drama, cyberbullying and hate speech; relationship communication; news and media literacy; and online privacy and security.

The last item, cybersecurity, looms huge on the horizon for K-12 schools. Hagel is hesitant to discuss the district’s vulnerabilities.

“What I would say is the FBI has come out this year and said that school districts are one of, if not the biggest targets on the internet right now,” he said. “But I can tell you that we’re partnering with the federal government and Homeland Security through some of their programs to tighten up our security posture here in the district.”

The big new thing

Hagel adds to the focus list artificial intelligence. Students with increasing ease can access online AI tools with potential outcomes — like everything tech-related — for good or ill. There are apps that will write a term paper for them. On the flip side, they could use an AI program to create new types of art or music.

How should educators harness artificial intelligence? That’s something Hagel and his peers nationwide are talking about.

With educational technology, there’s so much ground to cover. The reality is there’s just not enough time to do it all, Hagel says, or even give teachers training to stay up to speed.

“Teachers have a lot on their plates, and trying to find time to fit in more things is just a humongous task that we’re really struggling with,” Hagel said. “You know, we need to respect teachers and their time, and we also need to get them this information, as well. And, so, we’re struggling on how to do that.”

The district is working with the teachers’ union on ideas and solutions.

Weeding through sources

Stacey Marten, library and information specialist at Gig Harbor High School, remembers the golden age of online education, when the proliferation of digital research tools, lesson plans, educational websites and textbooks was gathering momentum.

A former social studies teacher, Marten decided in 2012 to get her library certification so she could direct teachers (and students) to the great online stream of knowledge and enlightenment.

Since then, however, specious sources and questionable information have clotted the system.

“Now you’ve got to kind of weed through,” she said.

Students present research based on “fake” sources that snag search engines.

“Or you have those weird little web addresses that send you someplace other than the one that you’re looking for. You know, there’s all kinds of traps,” Marten said.

Phone zombies

Over the past eight years that she’s been at Gig Harbor High, she’s also noticed cell phones commanding more and more of students’ attention.

“Now, you can watch kids just walking around with their heads down. They’ll run into each other or they’ll run into something,” she said.

The pandemic accelerated online trends. Students stuck at home spent more time texting, playing games, and creating or consuming content.

“Coming out of the pandemic, we’re seeing behaviors that our younger kids are doing. Things that we used to see in middle school are now occurring in elementary school,” Hagel said. “I think a fairly common assumption right now is that kids had more time on devices. Kids had more free time to explore than they typically would during the pandemic, to explore things online.”

Seeking connection

Parker said for her and her peers, online communication during the pandemic helped fill a craving to connect with others. It also created a private space for teens. That’s not necessarily a bad thing.

“So, it becomes a hard balance, you know, of having your parent check your phone and you feel like that’s somehow violated” your privacy, she said. “We just want that connection with people. But because especially over these past two years, we’ve just strictly been subjected to being in our rooms on a computer over Zoom, so, there is that lack of ability to socialize.”

Parker agrees that digital citizenship should be part of K-12 education. She said students have a role to play in creating a healthy culture around technology use.

“I think there’s no way to change the way the technology will be used unless it starts with the generation where it’s affecting the most, because we know the most about it,” she said.

Starting conversations with kids

The goal is for digital citizenship to be woven throughout the instructional day. That’s not always happening, Marten said. “I would say it’s never been consistent.”

Teachers can use her as a resource on media literacy but not all do.

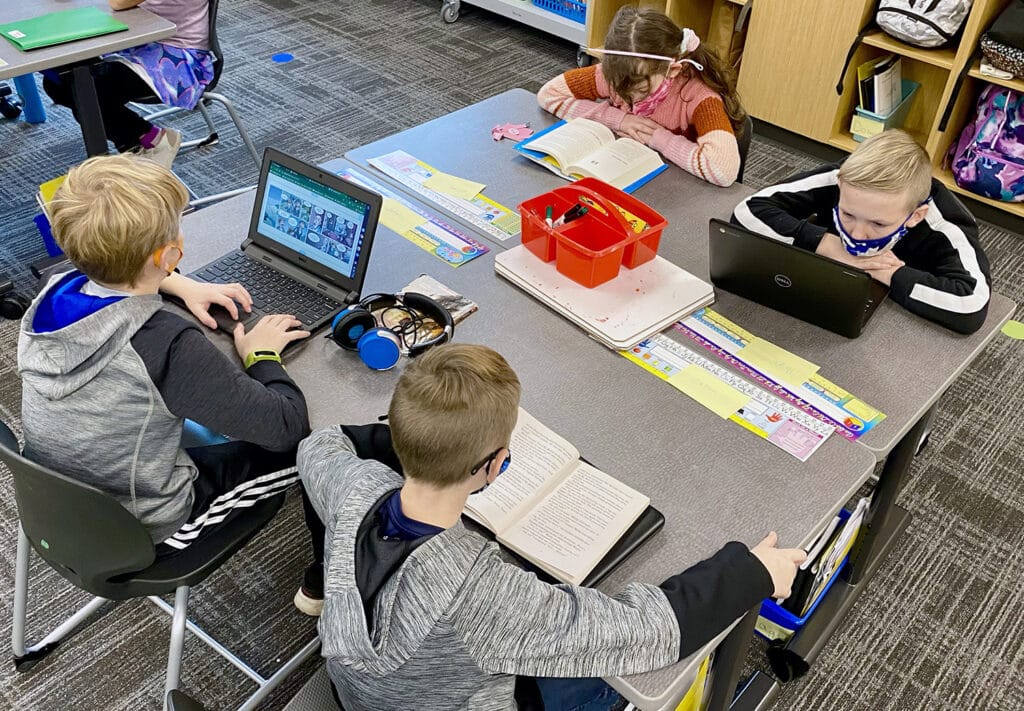

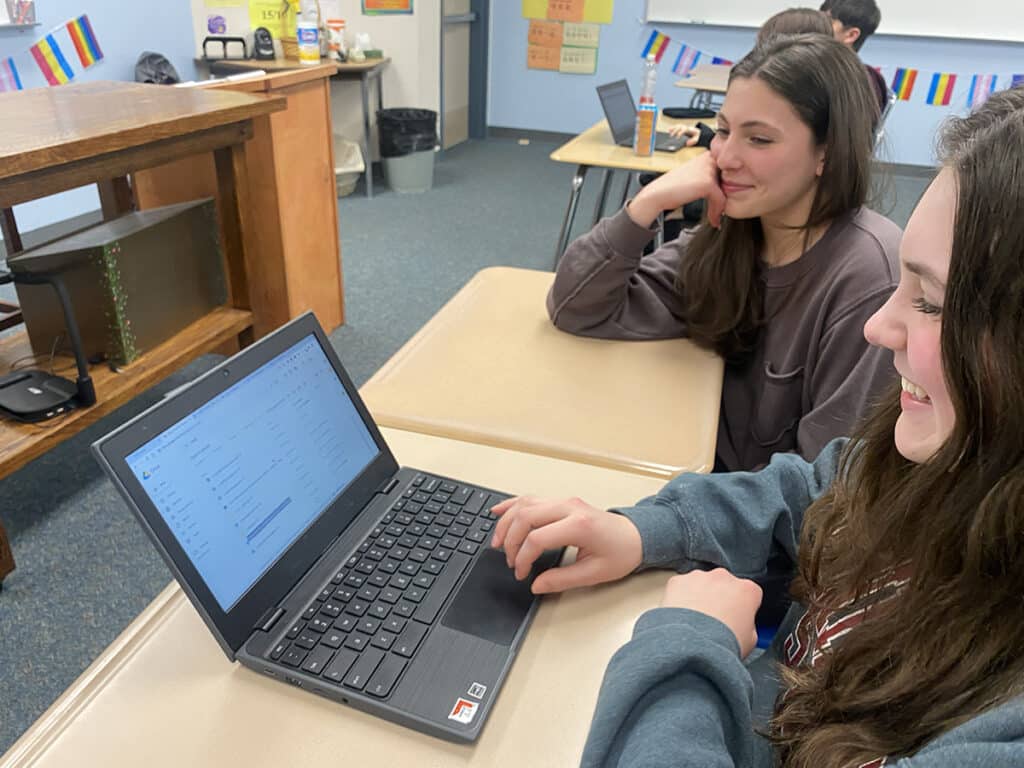

Most subjects in school involve use of online tools or research. Peninsula School District’s efforts to educate students about “digital citizenship” are a key component.

“It’s not necessarily like a curricular unit,” she said. “However, if they do research for a particular unit, they will ask me to come in and provide information, like, on research and making sure that the articles that they’re finding come from databases, have authoritative figures behind them who have credibility, things like that.”

Certain classes, like math, don’t easily lend themselves to conversations about media literacy, digital footprints and online safety. So, the exposure students get to those topics varies.

Tides Time

At Gig Harbor High, a new initiative called Tides Time is proving effective in getting those conversations started.

During the pandemic, teachers met with small groups of students regularly to address “social emotional learning” issues. Each group stays with the same teacher throughout their time at the high school, basically an advisory group. Among general discussions about students’ mental health and other issues, topics related to online learning and networking became highly relevant.

“We carved out a time and it started as two days a week. And because we were online at the time, it was on Zoom,” Marten said. “But that has provided us an avenue to be consistent throughout the school in teaching some digital citizenship lessons.”

The advisory groups that have continued meeting, now in person, adapted lesson plans from Common Sense Media.

Computer science and math teacher Sam Tilly leads a freshmen Tides Time group. A recent session centered on how to spot a digitally altered video and how information deleted from social media may surface again.

“There’s been pretty good discussions on that,” Tilly said.

Marten thinks Tides Time is the perfect way to get information on digital citizenship out there, at least for now. The teaching staff plans to increase the content next year.

“So, we’ll find our way and we’ll keep incorporating more as we figure it out,” she said.

Partnership with parents

Hagel spoke in March to the district’s Parent Council on efforts to promote digital citizenship.

Among useful resources for parents, he mentioned Securly, the program Peninsula School District uses to control students’ Internet access on district-owned devices. Securly is available to parents, as well. They can use it to see what their students have been accessing, and to set filters and time limits.

As for the eternal question of “how much screen time is too much?” Hagel cites author danah boyd, author of “It’s Complicated: The Lives of Networked Teens.” Boyd says it’s not the media they’re addicted to, it’s one another.

And there are different types of screen time. Mindlessly scrolling alone in your bedroom is not the same as creating or connecting meaningfully online.

“I guess it just brings to light how concerning it all can be as a parent and as a teacher,” said parent Karmen Furer of Hagel’s presentation that covered all the bases, from media balance to cybersecurity. “And I think our teachers and educators do a really good job of trying to communicate that with the kids.”

How young is too young?

That said, Furer acknowledges the often-tough role parents play. Furer’s middle-school daughter is not allowed to used social media, unlike some of her peers. She has a cell phone to text and communicate with her family on pick-up times and such.

“I’m nervous to let my middle-schooler have unsupervised access,” Furer said. “But I think it’s hard because I feel like a lot of her peers do. So, what’s that balance of being too controlling versus letting her figure out her own way?”

Furer appreciates the support from her kids’ schools and realizes it’s a two-way street.

“I think that, you know, parents, we need to partner with our teachers and our district to make sure that we just can kind of be a united front, and supporting our kids and navigating through this world because it is very different,” she said.

The district this fall plans more parent forums on the topic of digital citizenship.