Community Government

Gig Harbor property tax bills spike

Gig Harbor homeowners received unwelcome news in the mail last week. Their 2023 property tax bills jumped significantly.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Those living in unincorporated areas will pay an average of $8,055 — $795 more than in 2022, an 11% increase. The average city dweller’s payment rose by $490 to $6,258, or 8.5%. Key Peninsula increased at a more modest 4.9%, from $4,908 to $5,148.

The Gig Harbor increases (along with 8.7% for tiny Carbonado) are the largest in Pierce County. The average tax bill countywide is $5,579, a 5.1% increase over last year. A few areas, including Edgewood (-3.8%), Wilkeson (-1.0%) and Sumner (-0.8%) saw declines.

House values up even more than taxes

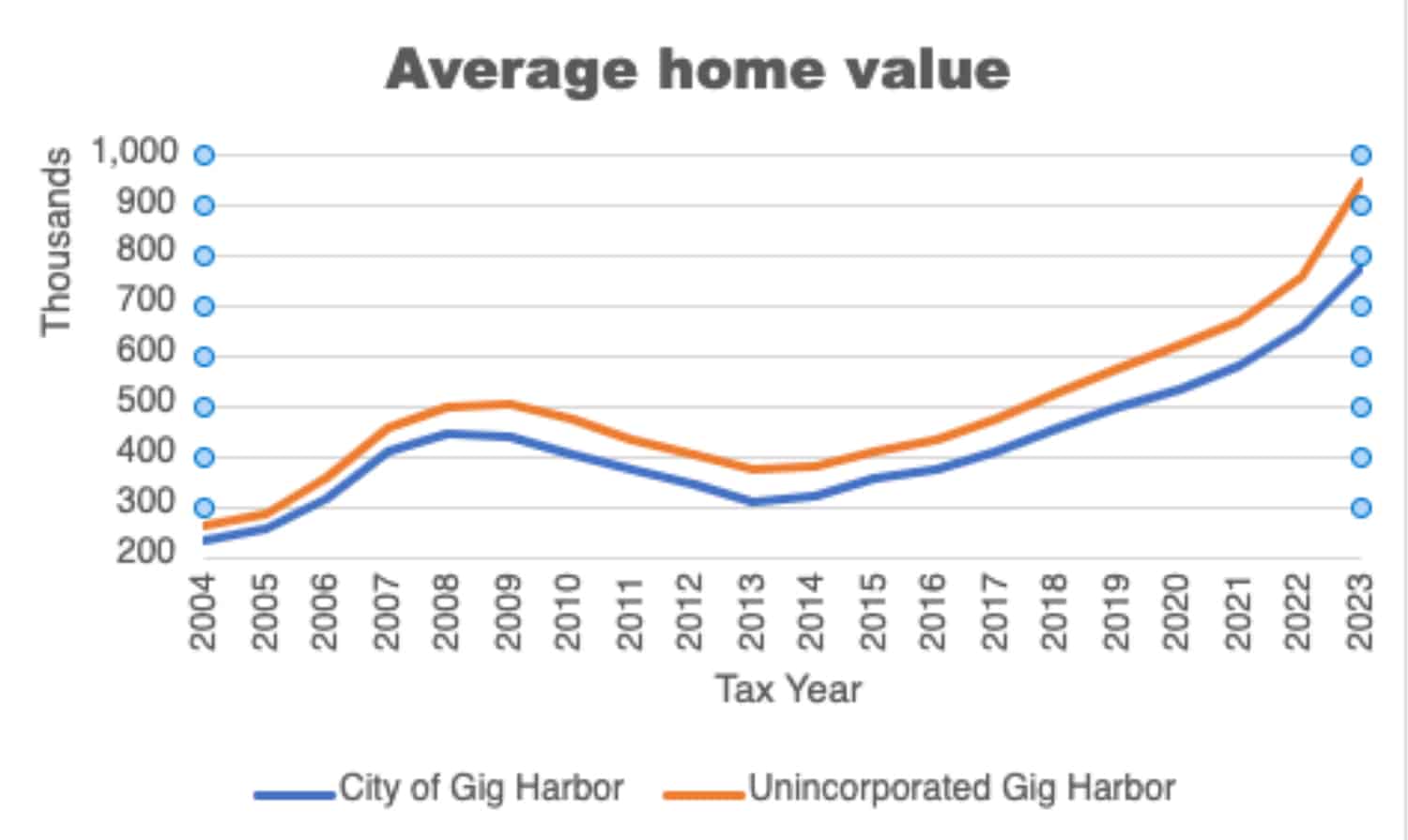

Skyrocketing housing values are responsible for part of the tax hike. In unincorporated Gig Harbor, the average home increased from $738,210 in 2021 to $916,038, the highest in the county. That’s a 24.1% jump in one year.

Next highest was the city of Gig Harbor, where values soared from $648,566 to $781,706, a 20.5% increase. Key Peninsula also spiked by 24.1%, from an average of $498,552 to $608,953.

Fire bond added to tax increase

“Much of the increase for the Gig Harbor area is due to the Fire District 5 general obligation bond and their EMS lid lift both passing in 2022,” said Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer Mike Lonergan. “That was the biggest change over last year’s taxes.”

Voters approved Gig Harbor Fire & Medic One’s 20-year, $80 million capital bond in August. Proceeds will allow the department to replace Station 51 on Kimball Drive, improve stations 53 (Fox Island), 57 (Crescent Valley), 58 (Swede Hill) and 59 (Artondale), and build a live-fire training facility.

At 23.8 cents per $1,000 of assessed value, it will cost the owner of the average $916,038 home in unincorporated Gig Harbor $219, and $186 for an average $781,706 home in the city limits.

Property owners continue to pay for Peninsula School District’s 20-year, $198.6 million capital facilities bond, passed in February 2019, that was used to build two new elementary schools and replace two others. The cost to taxpayers is 79 cents per $1,000 of value — or this year about $724 for an average house in unincorporated Gig Harbor and $618 in the city.

Bonds are not subject to the state’s 1% limit. Property owners pay the same rate per $1,000 during the bond’s life, which results in higher taxes each year as their home values increase.

Levy lid lifts bypass 1% limit

Gig Harbor Fire’s six-year emergency medical services levy lid lift that passed in November is a renewal of a previous one. Lid lifts contribute to property tax increases by allowing taxing districts to exceed the state’s 1% limit and collect the full rate approved by voters. In this case, the rate remains at 50 cents per $1,000 of property value, but the district collects more each year as home values rise.

Voters also passed a levy lid lift to allow the fire department to collect its full $1.50 for firefighting. It expires this year and Chief Dennis Doan has said the district will seek a renewal.

Peninsula Metropolitan Parks District passed a lid lift allowing it to levy the full 75 cents per $1,000 of value from 2018 through 2023.

School districts have their own formula that allows them to levy up to $2.50 per $1,000. Peninsula is currently capturing $1.72 per $1,000 overall, Lonergan said.

Two school levies passed earlier this month won’t affect property taxes until next year. The three-year Replacement Educational Programs and Operations Levy will collect $1.13 per $1,000 of assessed value in 2024, $1.12 in 2025 and $1.10 in 2026. The Safety, Security and Technology Levy rate will be a flat 25 cents per $1,000 over six years.

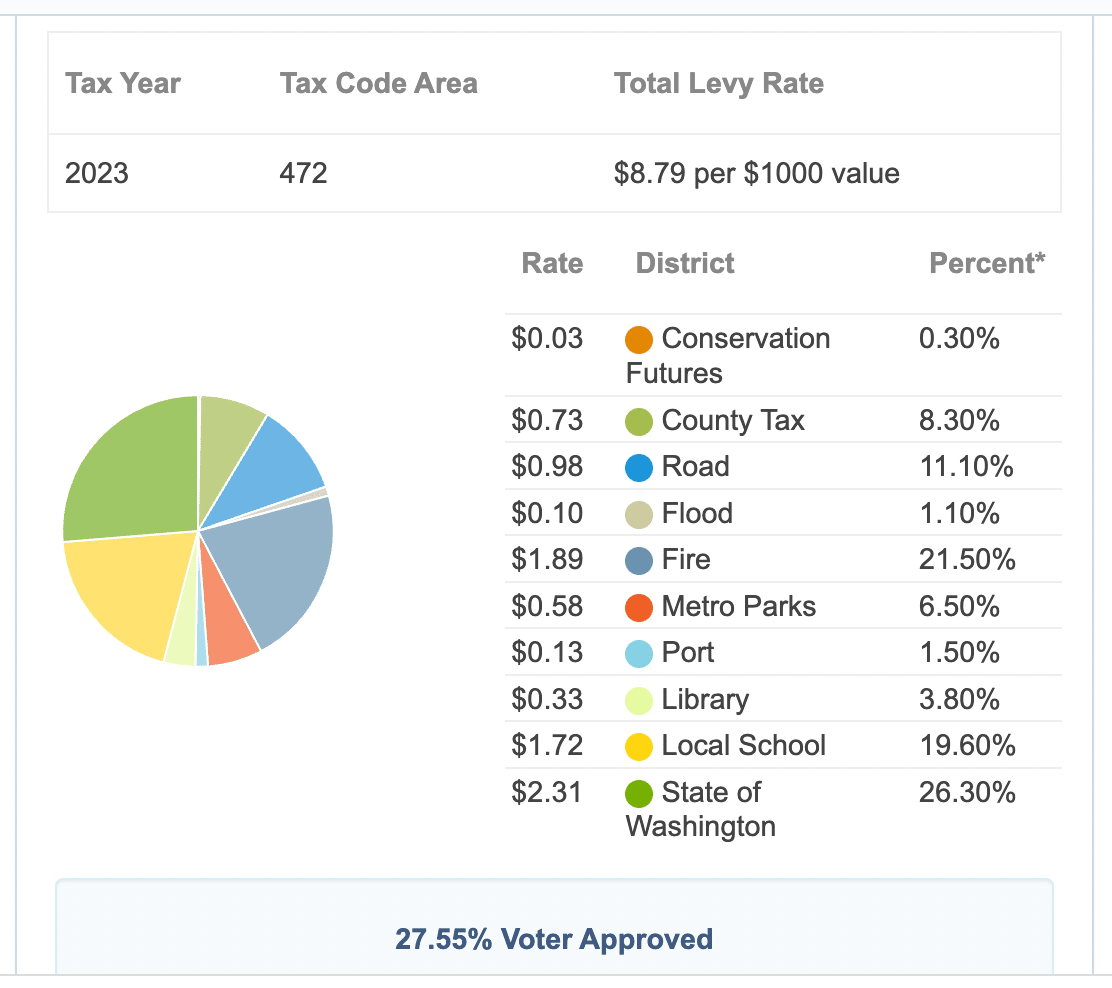

The total levy rate for unincorporated Gig Harbor is $8.79 per $1,000 value. It primarily comprises state schools (26.3%), fire (21.5%), local schools (19.6%), county roads (11.1%), county operations (8.3%) and parks (6.5%). About 27.6% was approved by voters. Those within city limits pay a municipal tax but don’t contribute to PenMet Parks.

Not enough houses for demand

Home values spiked because of an insufficient supply fanned by factors unique to the time.

“That’s true throughout the county, region and United States,” said Michael Robinson of Windermere Professional Partners in Gig Harbor. “We don’t have enough housing to meet the demand.”

On May 2, 2022, 120 Gig Harbor area properties were pending (demand) while 57 were active (supply), said Robinson, scrolling back through data to a frenzied period.

“Demand is outstripping supply,” he said. “There were 2.11 buyers for every home for sale. So when you have that kind of environment, prices are going to go up.”

The shortage led to price wars for homes, with offers exceeding list price, cash purchases and waiving of home inspections. As of last Monday, the market had cooled to 72 houses pending and 90 for sale.

So why isn’t there enough housing?

“Because the cost of entitlements and land are so high that you can’t build affordably,” said Robinson, who has been selling homes since 1994. “Something north of 27 cents of every dollar in a new house is for taxes, permits and entitlements. It’s just really hard to build.”

“We need zoning to allow higher-density housing. We need more places for people to lay their heads and own it, and it needs to be affordable. Then we can balance out the supply-and-demand issue. But nobody wants that in their backyard.”

Interest rate fears fueled buying spree

A fear of imminent interest rate hikes to tame inflation exacerbated the housing shortage. Though the average rate since 1971 is 7.75%, and peaked in 1980 at 19%, most potential home buyers assumed they would remain at sub-4% levels. And they likely would have had the federal government not stimulated the economy after the COVID pandemic.

“As inflation moved out of control and they started to comment on moving interest rates up, buyers who were sitting on the fence at the end of 2021 decided they needed to get into something in 2022,” said Paige Schulte, founder of Neighborhood Experts Real Estate in Gig Harbor. “It was just the time to get a house at a 4% interest rate. There weren’t 2s or 3s anymore. It was a run on interest rates for an affordable mortgage, not necessarily the price of the home.

“They were willing to pay exponentially more for that interest rate. The extra price of $10,000 to $20,000 financed at a lower interest rate was worth it.”

Property taxes on the average home in the city of Gig Harbor increased by 8.5%. Ed Friedrich / Gig Harbor Now

Also, Gig Harbor pushes the edge of where Seattle tech workers, pilots and military officers will commute.

“This is where they all put down roots, because of our schools, because of our amenities, because it’s beautiful,” Schulte said.

Millennials become buyers

Millennials were stereotyped as a renting generation, but as they entered prime home-buying age — they’re now 27 to 42 years old — that changed.

“It turned out that was completely wrong,” Robinson said of what is now the country’s largest generation. “Home ownership is part of American life. When you get married and have children, you think about a house differently.”

And COVID enabled more of them to work remotely.

“People don’t have to live near where they work,” said Robinson. “If I have to commute to Seattle but only have to do it twice a week, I’ll buy in Pierce County, and Gig Harbor is beautiful.”

Interest rates, millennials and remote work all boosted demand, which raised values.

State law requires the county assessor-treasurer’s office to value property at 100% of the true and fair market value. That is defined as the price a willing buyer will pay a willing seller. They are based on recent similar sales, and can be appealed.

Though it might seem that property values rise every year, that’s not always the case. During the late 2000s, banks were making loans people couldn’t afford, resulting in foreclosures and many homes on the market. The average home value in Gig Harbor city limits dropped from $445,559 in 2008 to $311,003 in 2013. It shot up 149% since then, however, and 155% outside the city.

The fear of rising interest rates sparked a house-buying frenzy that raised prices. Ed Friedrich / Gig Harbor Now

Taxes are collected on a combination of residential and commercial properties, vacant land and personal property such as store equipment. The share shifted this year as commercial properties were slow to recover from COVID. Workers haven’t returned to the office, resulting in vacancies, loss of building value and even conversion to living spaces.

“An additional factor (in property tax increases) is that most commercial properties did not increase in value nearly as much as residential, so there was a shift toward residential paying a larger share of the tax,” Lonergan said.

A bill allowing taxing districts to raise rates up to 3% annually instead of 1% recently passed the House Finance Committee. If approved, it would go into effect beginning next year.