Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | WWII-era incendiary balloon was a mere inconvenience on the Key Peninsula

Our previous column noted that in a unique event, a Japanese incendiary balloon designed to set the forests of the Pacific Northwest aflame landed on the Key Peninsula in 1945, near the end of World War 2. The topic generated three questions.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Where did the Japanese incendiary balloon land on the Key Peninsula?

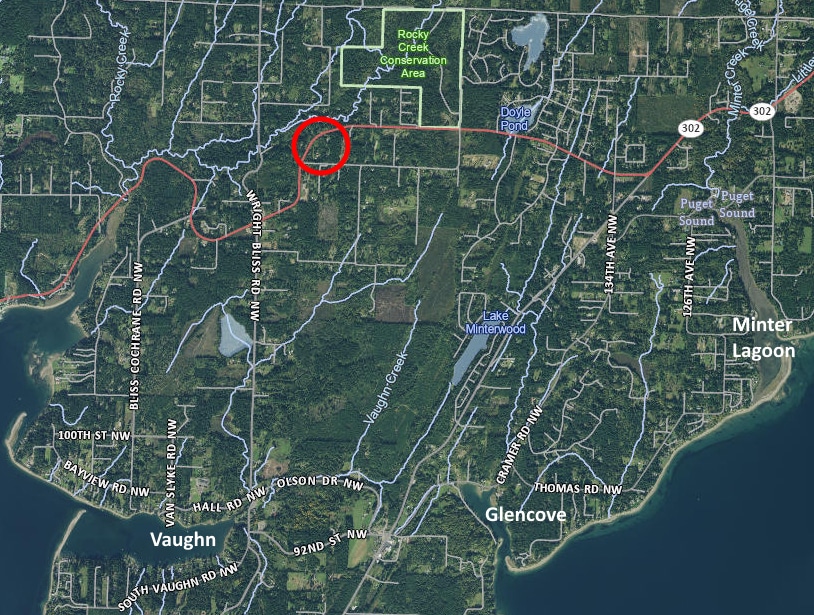

Answer: On the Jaggi property, about a mile and a quarter west of Lake of the Woods (aka Doyle Pond).

A Japanese incendiary balloon, designed to set the forests of the Pacific Northwest on fire, landed on the Key Peninsula in 1945. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Fred Jaggi and his young son Fritz heard something being dragged across the roof of their home. When they went outside to investigate, they found the balloon had cleared the house and ended its transpacific flight tangled in nearby power lines.

The enemy weapon no longer had its explosive charges. But current Crescent Valley resident Gary Lodholm, who was living in Purdy at the time, remembers that it managed to knock out the Peninsula Light Company’s feeder line to Grapeview.

His father, Oak Lodholm, the general manager of the electric utility, was among the crew that responded to the outage. Gary can also recall with some detail the U.S. Army truck that arrived to haul the balloon away — but not before Oak took a small piece of the contraption as a souvenir.

The Key Peninsula’s lone WW2 enemy attack was a failure by every measure. The balloon’s incendiary bombs, dropped who-knows-where, didn’t set any fires. Its anti-personnel bomb, also missing, didn’t kill any people. Every balloon sent by the Japanese had a self-destruct mechanism that was supposed to be triggered after the release of the explosive payloads, and that failed too. The coincidental power outage it caused was nothing more than a minor inconvenience to a few hundred people.

Why was the landing of the balloon not reported in the press?

Answer: At the military’s request, the press didn’t report on the balloons that landed in the United States.

The age-old (and bogus) story of not wanting to panic the public was not at play. The public was aware of the balloons. The reason the military didn’t want newspaper and radio coverage of the landings is because the balloons were causing no meaningful damage. If the Japanese knew that, they might try to do something to make them more effective.

Only one out of an estimated 9,000 balloons launched was even partially successful, killing six civilians in Oregon. None sparked fires of any consequence.

What was the major flaw of the incendiary balloon program?

Answer: Jet stream winds strong enough to carry the balloons from Japan to North America are seasonal, from November through April. Those are the wettest months of the year in the Pacific Northwest, when it’s virtually impossible to start forest fires.

The Japanese incendiary balloon program was a complete failure, having had not the slightest affect on the conduct or outcome of the war.

A quick digression on household voltage

Assuming a non-existent relevance between the previous segment and this one, we now make an awkward segue from a single WW2 power outage to modern electrical service.

Everybody knows that the electrical outlets in the walls of their house provide 110 volts, right? And that major appliances like clothes dryers, stoves, and ovens use 220 volts?

No, not really.

Those are voltages of another era. It’s a prime example of language momentum. Many people still call household voltage 110 because that’s what they’ve heard all their lives. But in spite of what they’ve heard, it’s never been true for most people alive today.

One hundred ten volts is distant history. (Which is why the subject is appropriate for this column, however clumsy the segue from the lead topic may have been.)

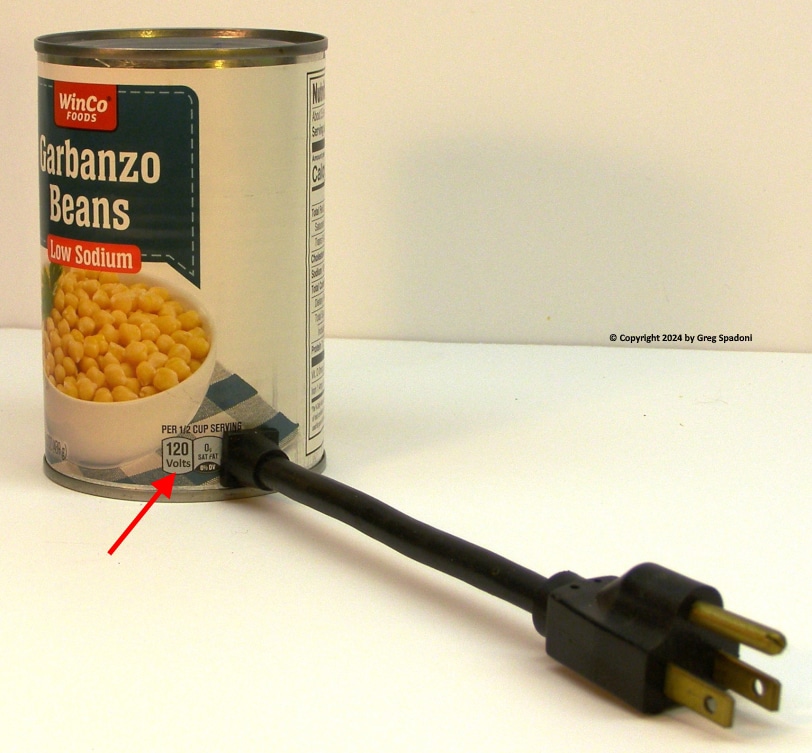

The standard household voltage in the U.S. today is stated as 120, but is usually a bit more than that. And in case anyone’s not sure, that’s AC, not DC.

Household wall outlet voltage is generally 120 volts or a little more, and has been for many decades. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Household voltage used to be 110 volts, back in Thomas Edison’s day. That’s where the number came from. But it was raised incrementally over a period of years, long before most of us were born.

It was increased simply because more electrical power can be transmitted on the same wire by using a higher voltage. If 110 volts was still the standard, transmission lines would have to be thicker than they are today to carry the same load, and as a result, more expensive. It all has to do with super cool science that makes for incredibly boring reading in a local history column. That’s why we’re only skimming the highlights.

While the stated standard household voltage today is 120 for wall sockets and 240 for major appliances, it can, and does, vary. When problems with the power distribution grid arise, sometimes the only way to keep affected neighborhoods online is to temporarily lower the voltage to everybody in that area.

It happens on rare occasions, although most people don’t notice a drop of maybe ten volts. But microwave ovens notice, and that’s what’s always brought it to my attention. Certain dishes that take a specific amount of time on a specific power setting aren’t done on time when the line voltage isn’t up to where it’s supposed to be.

It’s just plain un-American when dinner is five minutes late.

Even America’s favorite self-cooking cans of chick peas, fondly and informally known for generations as One-Ten Garbanzos, have been 120 volts for many decades. (And zero saturated fat!) Photo by Greg Spadoni.

It would be OK tonight, though. It just so happens that in a store this morning, I heard the seductive whisper of Peanut M&M’s calling to me. Surrendering to temptation, I grabbed the last three bags. I can eat those if dinner’s not on time this evening.

And now that I think about it, those just might be dinner tonight. Why bother to cook when you already have three bags of the world’s most perfect food?

It’s extra satisfying that the world’s most perfect food doesn’t even need cooking. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Caught flat footed

Being charged with the simple task of coming up with one, single, usually simple, local history question every other week is not exactly a daunting challenge. Yet here I am, questionless as this week’s deadline has arrived. I have no one but myself to blame, and offer no excuses except to claim that my dog ate my homework, though that’s not likely to fool anybody. I can only … wait a minute — there’s a late dispatch coming across the Teletype …

Stand By.

… Just received from the Gig Harbor Now and Then Ridiculous But True Department, it is indeed a question of local history, and a good one, too. It reads:

What was the name of the ice delivery man in Gig Harbor in 1931?

Due to the blatant hint given by the source of the question, it’s not a difficult one. It shouldn’t take more than a few simple, obvious guesses to come up with the correct answer.

In fact, it’s so easy that I’m going to try to come up with the answer myself. If I do, it will be prominently featured in this column on Feb. 26. If I don’t, I’ll come up with some lame excuse. I’ve got plenty of those.

If you’d like to share a guess answer to this week’s question on the Gig Harbor Now Facebook page, be our guest. Maybe just before dinner? You could easily do it during the time it takes a can of One-Ten Garbanzos to cook.

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.