Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then: The search for a needle (or a stabilizer) in a haystack (or Burley)

Our previous question of local history concerned a cash reward offered for the return of a critical piece missing from a Boeing B-17 bomber that crashed in Burley in March 1943.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

How long did the kids of the Burley/Glenwood/Purdy area search for the bomber’s missing part?

Answer: All through the summer of 1943.

During a conversation I had with Charlie Sehmel in 2018, he mentioned that he grew up in the Glenwood area (near Burley) in the 1930s and ’40s. Having thoroughly researched the crash of the B-17F, and always open to new information on local history, I asked him if he remembered the incident. Yes! I had now found a third witness to either the crash itself or the immediate aftermath.

Among other interesting details, he said that Boeing offered a reward for the return of the missing horizontal stabilizer. He and his friends, filled with enthusiasm, would get on their bicycles and ride to various places in the area to search for it. They did that all summer, he told me.

In response, I had something to tell him: Boeing had found the missing assembly within three weeks of the crash. That fact is documented in the official U.S. Army Air Forces accident report, complete with a dated photo of the recovered part. Apparently, Boeing didn’t bother to tell the public … or was it the parents who never bothered to tell their children? After all, it did give them something to do.

This perfectly restored B-17F, identical to the one that crashed in Burley, can be seen at the Museum of Flight in Seattle. Photo courtesy of The Museum of Flight.

Boeing made fixes

Recovery and study of the mangled left horizontal stabilizer (left rear wing) allowed Boeing to come up with an improved manufacturing method to prevent the failure suffered by the bomber in Burley from happening to all future B-17s. The company’s engineers also devised a retrofit kit to repair the affected airplanes already in service — over 1,000 — including B-17F #42-29782, in the collection of the Museum of Flight in Seattle, and the most famous Flying Fortress of them all, Memphis Belle, on permanent display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force near Dayton, Ohio.

Recovery and study of the crashed bomber’s left horizontal stabilizer allowed Boeing to devise a field retrofit to prevent other B-17Fs already in service, including Memphis Belle (seen here after a complete restoration), from suffering the same fate. U.S. Air Force photo by Ken LaRock.

It’s worth noting that a pair of wheels and tires used on B-17s is on permanent display outside the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor. They are attached to the Spadoni Brothers’ logging arch, which they built after the war using a set of surplus main landing gear for a Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bomber. (The two airplanes used the same tires and wheels.)

Although it might seem nearly impossible to find the answer to this question, its degree of difficulty was rated at 4 out of 5 instead of a 5 because the crash of the B-17 was witnessed by hundreds of people, a few of whom are still living. Any one of them might recall the search for the reward, as did Charlie.

If any reader happened to know the answer before Gig Harbor Now and Then posted it, I’d sure like to know how!

In 2014, armed with the property owner’s permission, a round-point shovel, and a friend with a high-end metal detector, Greg Spadoni went in search of proof that he’d figured out exactly where B17F #42-29932 hit the ground in Burley 71 years prior. He found it within minutes. This is the whip antenna base from the crashed B-17. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Next question: Military reservations and squatters

In not quite a smooth and seamless transition, we now pivot from bombers to squatters. The common thread is the U.S. military, but only in concept. As reality played out, the military wasn’t involved in this week’s subject, although the word “military” was prominently attached throughout. Today’s question has to do with squatters on a military reservation.

There were three primary ways to settle on a piece of government land on the early Peninsula, two of which involved very hard work:

- You could stake out a claim and homestead it, a process by which you received the land for free after a certain number of years, providing you fulfilled the requirements;

- you could file a preemption claim and buy the property, providing you fulfilled the requirements (which were fewer than with homesteading);

- or you could simply buy a piece of land outright.

There was also a lesser-used fourth way, which was a combination of the first two methods, plus the added thrill of a game of chance. Squatters often employed the fourth approach.

In the early years of non-tribal settlement, an assortment of squatters were scattered across the Gig Harbor and Key peninsulas. Only on the Gig Harbor side were they concentrated in bunches. It was the multiple U.S. military reservations there that drew the concentrations.

What’s a military reservation?

Averaging between 600 and 700 acres each, the reservations were, in effect, exclusion zones for settlers. Homesteading was not allowed on them, nor was squatting, and because they were reserved for a specific purpose, none of the acreage was available for purchase by the public.

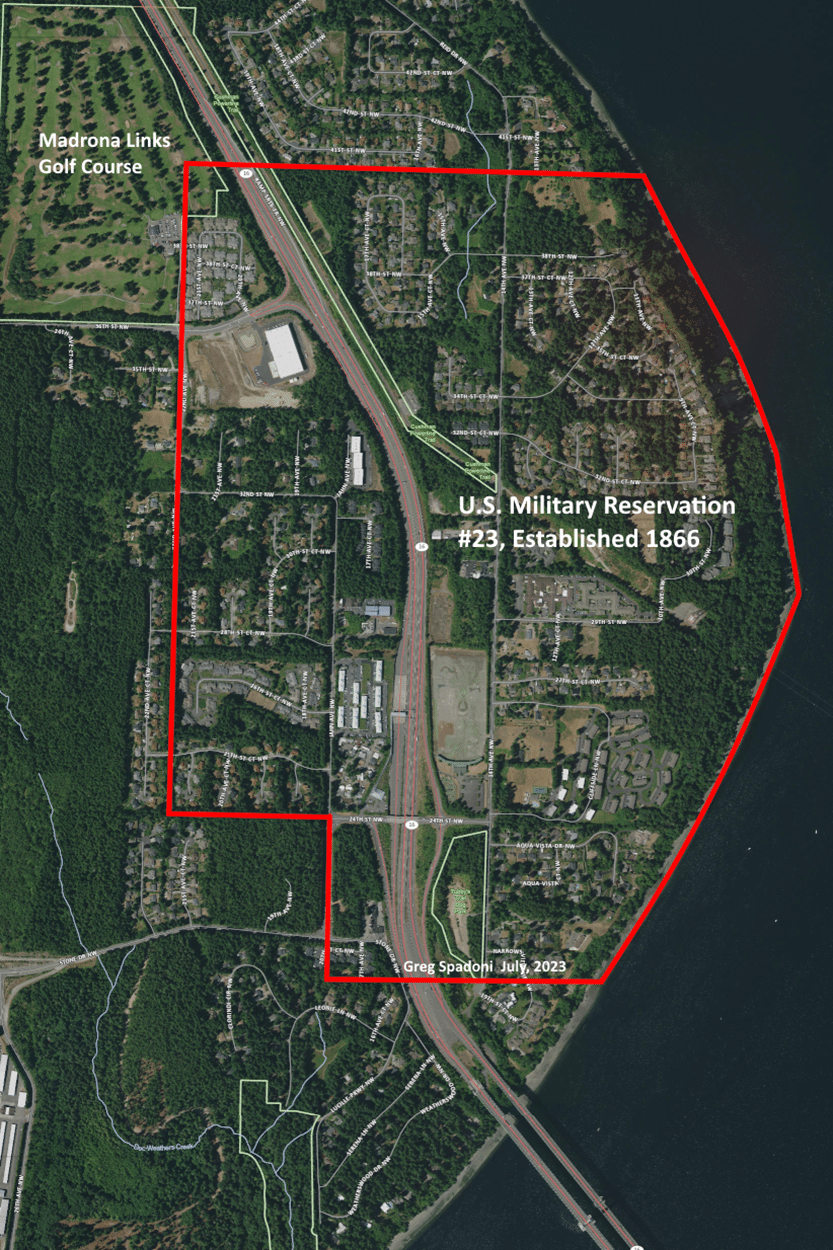

The boldest of the squatters, unbothered by pesky federal laws, moved to the military reserves anyway. It was their hope (and gamble) that by working as hard on their squatted acreage as homesteaders did on their claims, the federal government would eventually allow them to buy the land. As of 1916, 32 people (or families) were squatting on Military Reservation 23, at Point Evans, along the Narrows.

Every time you drive between Gig Harbor and the Narrows Bridges on Highway 16, you’re traveling the full length of Military Reservation 23. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Today’s question, concerning the lifestyles of the occupants of Military Reservation 23 in 1916, is this:

Measured in square feet, what was the average size of their 32 houses?

The degree of difficulty this week is probably a 3 out of 5. Of course no one’s going to already know what the average size of the squatters’ houses was on Military Reservation 23 in 1916, but the necessary raw information can be found through a Google search, on a single page. You’d have to do the arithmetic yourself, though.

For those not inclined to go searching for it, Gig Harbor Now and Then will have the answer in two weeks. In the meantime, you’re invited to visit the Gig Harbor Now Facebook page and post your guess and other thoughts about today’s question, and read what others have to say about it.

Comments on the answer given today are also welcomed, and it’s hard to imagine that a story of a brand-new B-17 crashing on the Peninsula during WW2 won’t generate comments. After all, B-17s are legendary, and now we know that part of the legend includes our narrow slice of the world.

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.