Community

City restores Native name to Austin Park area

For thousands of years before Croatian fisherman came to what’s now Gig Harbor — centuries, even, before sailors rowing a gig from the Wilkes expedition “discovered” the harbor in 1841 — the Puyallup Indians established a village at the north end of the bay. They called the area “twawalcut,”— txʷaalqəł — “place where game exists.”

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Visitors enjoy Austin Park where signs will outline the history of the Native people who originally lived there. Charlee Glock-Jackson / Gig Harbor Now

The village was home to a band of the spuyaləpabš — known today as the Puyallup Tribe of Indians. They were called the sx̌ʷǝbabš, meaning Swiftwater People. They lived in three connected areas, with a longhouse at Donkey Creek and a smaller site at Crescent Creek. Young warriors lived at a site at Wollochet. The warriors were guardians of the village, indeed, of the entire Narrows passage, and were well known as canoe builders.

As with all Native people prior to the arrival of white settlers, the sx̌ʷǝbabš lived, fished, hunted, raised their children, practiced their religion and used the natural resources along the waterfront, hillside, creeks and islands. The Medicine Creek Treaty of 1855 changed all that.

Tribes throughout Washington state were forced to relinquish claims to their traditional homelands and were forced to live on reservations. Most of the longhouses and other buildings that had been homes of extended families were destroyed, and places were renamed. In Gig Harbor, not a single street or landmark had a Native name. Until recently.

The Our Fisherman — Our Guardian sculpture by Guy Capoeman will be erected at Austin Park. Image courtesy of city of Gig Harbor

In September 2020, led by Mayor Kit Kuhn, the Gig Harbor City Council passed Resolution 1186 declaring the second Monday in October as “Indigenous Peoples Day” and the month of November as “Native American Heritage Month.” It also called for the Puyallup Nation flag to be flown in the Council chambers every October and November in perpetuity.

Resolution 1186 acknowledged that the town is built on the homelands and villages of the sx̌ʷǝbabš band of the Puyallup Tribe. It also calls for recognition of the contributions the Tribe has made to the area and commits the city “to continuing its efforts to promote the wellbeing and cultural vitality of Gig Harbor’s Indigenous community.” It codified that at the beginning of every regular business meeting of the City Council in October and November, the mayor “shall read the following land acknowledgment: ‘Before we begin this Council Meeting we would like to recognize that we are gathered on not only the ancestral and traditional lands of the sx̌ʷǝbabš band of the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, but also on the site of one of the largest and long-standing historic villages of the people, the original inhabitants of Gig Harbor.’”

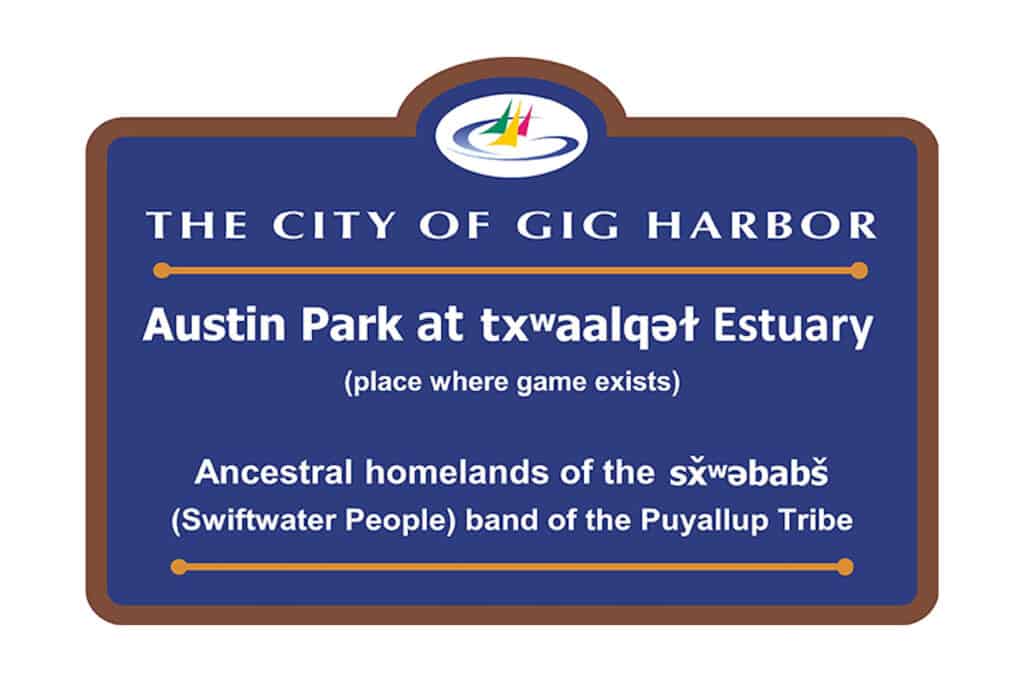

Proposed signage that will be installed at Austin Park, explaining the area’s Native history. Illustration courtesy of city of Gig Harbor

But Resolution 1186 was just the beginning.

Kuhn also formed an ad hoc committee comprising members of the City Council, the Puyallup Tribe, the Arts and Parks Commissions and several citizens to work together to designate Austin Park and surrounding waters and lands as an honorary historic area, recognizing the ancestral homelands of the Swift Water People and, specifically, their former village along the Gig Harbor waterfront. In essence, the committee’s goal was to restore the historic, tribal name to the 7-acre estuary area, including what was known as Austin Estuary Park.

On recommendation of the Arts Commission and Parks Commission, in February, the City Council approved Resolution 1199, re-naming the park and “designating the txʷaalqəł Estuary in honor of the sx̌ʷǝbabš band of the Puyallup Tribe.”

The estuary includes North Creek and the Harbor History Museum and other lands in and around Donkey Creek and Austin Park, located within the North Creek watershed, according to the resolution. In addition, city staff is working to establish an honorary historic area along the waterfront to recognize the extent of the sx̌ʷǝbabš band’s ancestral homelands.

In early September, new signage was installed at the park’s entrance identifying the site as Austin Park at txʷaalqəł Estuary and the ancestral homelands of the sx̌ʷǝbabš (Swiftwater People) band of the Puyallup Tribe. There is also a voicebox with recorded messages telling a brief history of estuary, with tribal members speaking the Lushootseed words.

A voicebox with recorded messages was installed at Austin Park. It tells a brief history of the estuary, with Tribal members speaking the Lushootseed words. Courtesy of city of Gig Harbor

Later this year, a 15-foot-tall carved cedar sculpture called “Our Fisherman — Our Guardian” will be installed on the shore. The sculpture was designed and created by Quinault Tribal Chairman Guy Capoeman and funded by the city’s Arts Commission, the Kiwanis Foundation and the Puyallup Tribe.

Kuhn has long been a human rights activist. “When I was growing up in Colorado, we were all very familiar with the Native Americans and what had historically happened to them,” he recalled. “My grandfather on my mother’s side was a writer for the Denver Post, and also an artist and a poet. He studied Native history a lot and even was allowed to participate in Native ceremonies in Boulder.”

Kuhn traveled a great deal and “wherever possible, I’ve focused on equal rights,” he said. After he settled in Gig Harbor, he wanted to learn more about what happened to the Native American people in Washington state. “I learned the truth at the history museum in Tacoma — how the white people brought disease and stole their land and so forth.”

As mayor, he was in a good position to lead the effort to undo some of the “invisibility” of the original inhabitants.

According to lifelong resident and former Gig Harbor City Administrator Mark Hoppen, the land side of the park was owned by Jerry Scofield and Hoppen’s mother, who then sold it to Pierce County Conservations Futures. From there it was transferred to the city of Gig Harbor.

A dozen or so years ago, the City Council voted to rename it in honor of the Austin family who had had a sawmill there. “The first naming was for the Austin family, partially because the above-water, land-side park area is basically wood chips from the sawmill,” Hoppen said.

In respect for the Austin family, Kuhn communicated with the remaining descendants and they agreed to drop the “estuary” from the park name. The Harbor History Museum staff and board also endorsed the name change. Kuhn has also worked closely with Tribal representatives to finalize the wording on the park signage and voice recordings, and on plaques that will be installed on five concrete pillars. They will tell the story of the sx̌ʷǝbabš and their deep roots in what is now Gig Harbor.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with new information provided by Mark Hoppen.