Business Community Environment

Crab fishing remains lucrative, critical industry for Gig Harbor fishermen

Off the coast of Washington, several Gig Harbor residents are hard at work on crab fishing boats, handling all that comes with the job.

Most people can conjure images of what it must be like, perhaps informed by the Discovery Channel show “Deadliest Catch.” Large crab cages, rough seas, a crew, and a lot of back-breaking hard work.

“We’ve spent years telling the city council that we are making livings, and some are making a great living,” said Guy Hoppen, a longtime Gig Harbor resident and fisherman. He is not a crab fisherman — he’s the president of the Gig Harbor BoatShop — but he is part of the fishing community who advocates for the development of the Ancich Home Port, a site for public fishing and moorage.

“Seasons wax and wane, but the bottom line is, great years bring a lot of money back to the community,” Hoppen said.

Licenses and leases

A handful of Gig Harbor residents hold commercial crab fishing licenses. Several others are crab license lease holders.

The state capped the number of available commercial crab fishing licenses at 220 in the 1990s. The intent was to manage crab populations, and also limit the amount of gear in the water to protect other sea life, such as whales, said Dan Ayers, coastal shellfish manager with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“Anyone who wants to enter the fishery must either have a current license that has to be renewed each year, or must lease a license from a license holder,” Ayers said. “Those deals are done individually, with no input, or involvement of the state. They work out a deal, and that arrangement is theirs.”

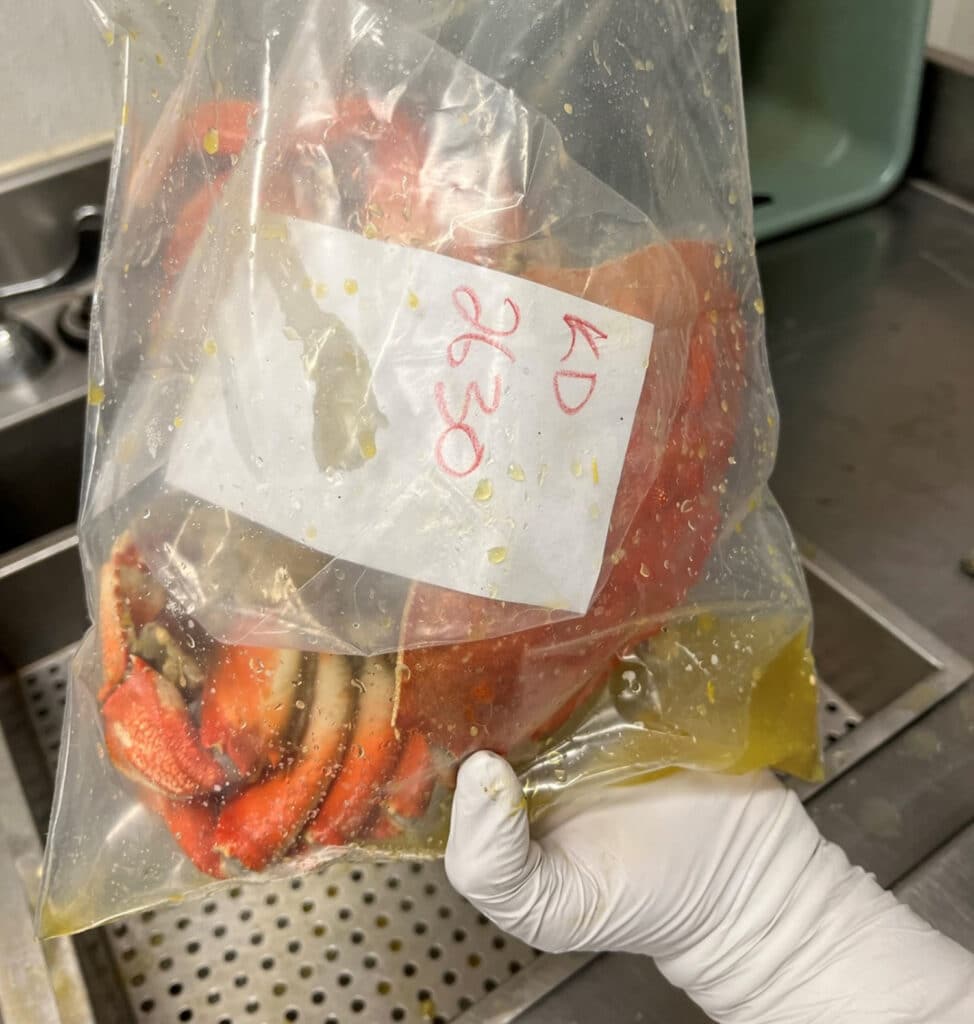

State biologists test-fishing for Dungeness crab.

A lucrative industry

Commercial crab fishing was an estimated $86 billion industry in Washington state in 2022. That total includes boat sales, gear, and processing facilities that handle the harvests.

The Dungeness crab fishery is the largest and most lucrative fishery in Washington, Ayers said. It’s much larger than the salmon or bottom fish industries.

“From a market standpoint, the main part of our job is to maximize commercial value,” he said.

Commercial crab fishing season officially opened Feb. 1 on the southern Washington coast and Feb. 6 for the rest of coastal Washington. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife sets those dates in conjunction with Oregon and California, the other participants in a tri-state agreement governing commercial crab fishing.

“We open close to the dates of California and Oregon,” Ayers said. “Once the season opens, it is open until Sept. 15. Most of the crab is caught by the first of April and there are far fewer in summer, but the region has fresh crab every day at some level.”

Snow crab in Bering Sea

Last October, Alaska closed its Bering Sea snow crab season for the first time. The Bering Sea snow crab population dropped by an estimated 90 percent.

The Washington coast has not experienced a similar decline in the Dungeness population, said Daniel Sund, the head biologist for Puget Sound commercial crustacean fisheries with DFW.

“The circumstances up in Alaska made them more sensitive to a large change,” Sund said.

Sund explained that a change in sea ice cover and the movement of other species into the Bering Sea likely contributed to the sharp snow crab decline.

“Some of the habitat the crab had from fish predation, those refuges decreased, and potential for predation from other species,” he said. “But our understanding of what has happened in Alaska is still very much in the works, and there is a lot of research still going on. In terms of our fisheries’ susceptibility to a change like that, we don’t have a sensitivity to it because we are in a slightly more temperate region.”

Water temperature

All West Coast fisheries are sensitive to changing ocean conditions, he said, and those changes can impact populations.

Scientists aren’t certain of the reason for the decline in snow crab in the Bering Sea. But Sund said smaller increases in temperature could impact Alaska water more acutely.

“Their (Bering Sea) species are probably more adapted to really cold waters,” he said. “I think we just don’t really know. There are a lot of studies being done on the coasts of Washington and Oregon to look at the effect of hypoxia, and areas where the oxygen can be depleted so quickly and they can’t get out quickly.”

It has not proven to be a problem for the coastal waters of Washington this season, he said. Other Washington waters, however, have seen seasons canceled.

Dungeness populations in the Gig Harbor area — the state designates the region as Marine Area 13 (south of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge) and Marine Area 11 (Tacoma-Vashon, including Gig Harbor) — have plummeted. Marine Area 13 has been closed during crabbing season since 2018.

Monitoring for toxins

For the commercial crab fishing businesses to thrive, the crab species must be viable and healthy for harvest.

Monitoring for shellfish toxins is a key step in that process. Tribal representatives, along with federal, state and local management and research agencies, work together on toxin monitoring as part of the Olympic Region Harmful Algal Bloom partnership (or ORHAB).

The agency monitors for a number of potential toxins, including paralytic shellfish poison, and diarrhetic shellfish poison.

Of special concern is domoic acid, a biotoxin linked to naturally occurring algal blooms. It can easily work its way up the food chain to crab.

The Washington Department of Health provided this photo of a Dungeness crab being prepared for testing at a lab.

Domoic acid fever can cause confusion, coma and even death. Among those who survive it, domoic acid fever can cause amnesia shellfish poisoning — losing the ability to form new memories. A person suffering from it can remember all past memories but can’t form new ones.

“We deal with this stuff year-to-year, and every year we see more,” said Joe Schumacker, marine resource scientist with the Quinault Indian Nation. “It seems to be increasing with climate change. The frequency and toxicity seems to be associated with warmer waters.”

Entanglements

With the economic stakes of the commercial crabbing industry so high for the state, it is imperative that it remain viable.

Ayers said the biggest challenge now is entanglement issues. According to Fish & Wildlife, “Commercial Dungeness crab fishing gear collectively makes up the largest portion of identifiable gear found in West Coast entanglement cases.”

Whale and marine turtle species are among those most likely to become entangled in fishing gear, according to Fish & Wildlife.

“We have a couple of people working just on that,” Ayers said. “We are taking some strides to address that. We’ve reduced the number of fishing pots they can use and we are taking steps to require that they mark their line so we can identify where it came from, and we can determine if it’s crab gear or something else. It’s important that we do this right.”

Ships line up for the Blessing of the Fleet in Gig Harbor in 2022. Vince Dice