Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Pioneers’ names got lost in translation

Old business

Last time’s question of local history came from an edited excerpt from “The Early Development of Gig Harbor, Washington” by Greg Spadoni, Copyright © 2021.

Researching real estate documents and newspapers from the early days of Gig Harbor is slowed considerably — and sometimes stopped outright — by the frequent and unpredictable changes in spelling of certain people’s names.

Why were there so many different spellings of single surnames on the early Peninsula?

Answer: There were two primary causes for the wide range of spellings. The significant number of local pioneers who were illiterate and could not tell others how to spell their names; and for those whose first language was not English, pronouncing their names for others to spell seems to have resulted in a different spelling each time.

However, those two reasons don’t explain some of the other local names that were commonly misspelled. The case of John and Josephine Novak is perhaps unique. Their last name went through almost as many different spellings as Dorotich’s. Narivitch (1882), Norovich (1887 Polk Directory of Puget Sound), Norovitch (1888), Norivitch, Novick and Novuk (1890), and Novauk (1893) were all applied to the couple’s name before Novak appeared in 1895. But Norovitch made a comeback in 1910, while Novock was the spelling in that year’s federal census. Novauk reappeared in 1914, before Novak ultimately became the standard.

Josephine’s first name was misspelled Zephina by Ira A. Town when he was writing real estate documents on their behalf in 1889. He corrected the record via affidavit in 1890.

It’s rather puzzling that in the affidavit Town, who had written most of the deeds and contracts the Novaks had made in the previous several years, said he had “misunderstood the name Josephine,” and had written on the documents “Zephina instead of Josephine as it should have been written,” yet in the following paragraph said that her name “had been and is Josephine” since his “acquaintance with her in 1884.”

That appears to be a rather dramatic example of how thickly accented John’s speech must have been — Ira Town had known the Novaks for five years, had previously written documents for them, and in 1889 still thought her name was Zephina.

But what about Josephine’s speech? She was not Croatian. She wasn’t a foreigner at all. Her heritage was half Native American, half Irish, with her entire life spent in Washington Territory. Though it’s possible, it seems unlikely she would have let John do all the talking if his speech was so difficult to comprehend. Could she have had a speech impediment that rendered her equally difficult to understand?

Skansie

Among quite a few others, the Skansie brothers, too, had alternate spellings of their last name.

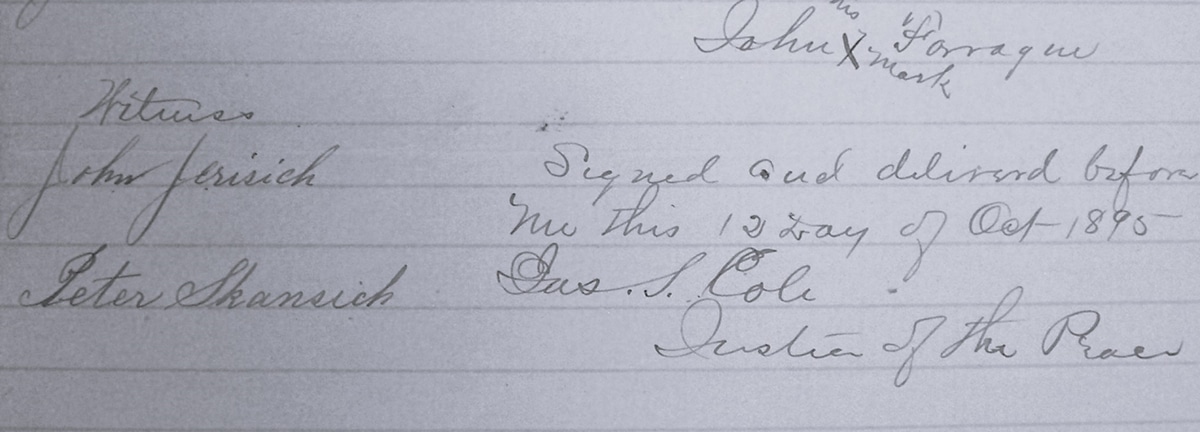

As a witness to a bill of sale in 1895, Peter’s last name was spelled Skansich, although it’s very possible it was written by someone else, and was not his signature.

As a witness to a bill of sale in 1895, Peter Skansie’s name is spelled Skancich. John Jeresich’s name is spelled Jerisich. This document is in the collection of the Harbor History Museum.

All the Skansie brothers used Skansi on some of the legal documents they signed from 1897 to 1921. Peter spelled his name Skansi when he married Melissa Jeresich in 1897, signed Skansie on an affidavit later the same year, used Skansie for a purchase of a building lot in Millville in 1909, yet appears as Skansi in a lawsuit against John Novak involving the same property. A newspaper report of the case spelled the name Skanski.

In 1903 The Seattle Daily Times misspelled Peter Skansie’s name as Skansia in reporting on his marriage to Kate Borovich. To make things even, it spelled her last name Broevich.

In 1916 Peter and Mitchell used Skansie on a real estate document, and they, along with Joseph, used the same spelling on a 1919 deed.

The two spellings of Skansi and Skansie are not the result of differing interpretations by others. Unlike most of the earlier Croatians in Gig Harbor, the Skansies were all literate. While it is believed by some people that they added the e to the end of their name to ensure the proper pronunciation (Skansee), that does not explain why some of them alternated between the two spellings for years before settling on Skansie.

Certain cousins of the Skansie brothers always used Skansi, as do those cousins’ descendants to this day. So both spellings are valid, depending on which branch of the family is being addressed.

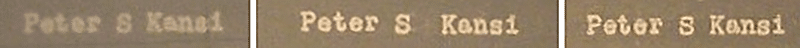

In a frightful misspelling of Peter Skansie’s name, at least from the point of view of anyone attempting to find his old real estate records, he was listed as Peter S. Kansi on a 1914 mortgage document. While that is obviously a mistake, it was not a simple typographical error, for it was written that way all three times he was mentioned.

Misspellings closer to home

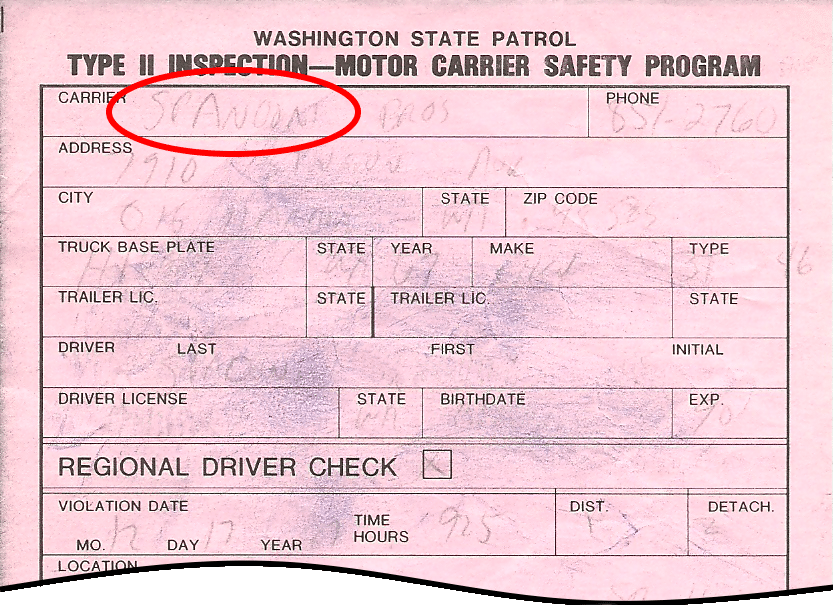

As might be expected, the name Spadoni has seen its share of misspellings too. By far the most common is Spandoni, where an extra “n” is mysteriously added before the “d.” Somebody with that last name really angered a Washington State Patrolman one time by pointing out the extra “n” he’d added to a warning ticket for no mud flaps on a dump truck. Whoever that was had to do some fast talking to calm him down and keep him from changing the warning to a pay ticket. “Everybody spells it that way! It’s very, very common.”

The Washington State Patrol added an extra “n” to “Spadoni” more than once, but a certain Spadoni Brothers dump truck driver learned the hard way not to point it out.

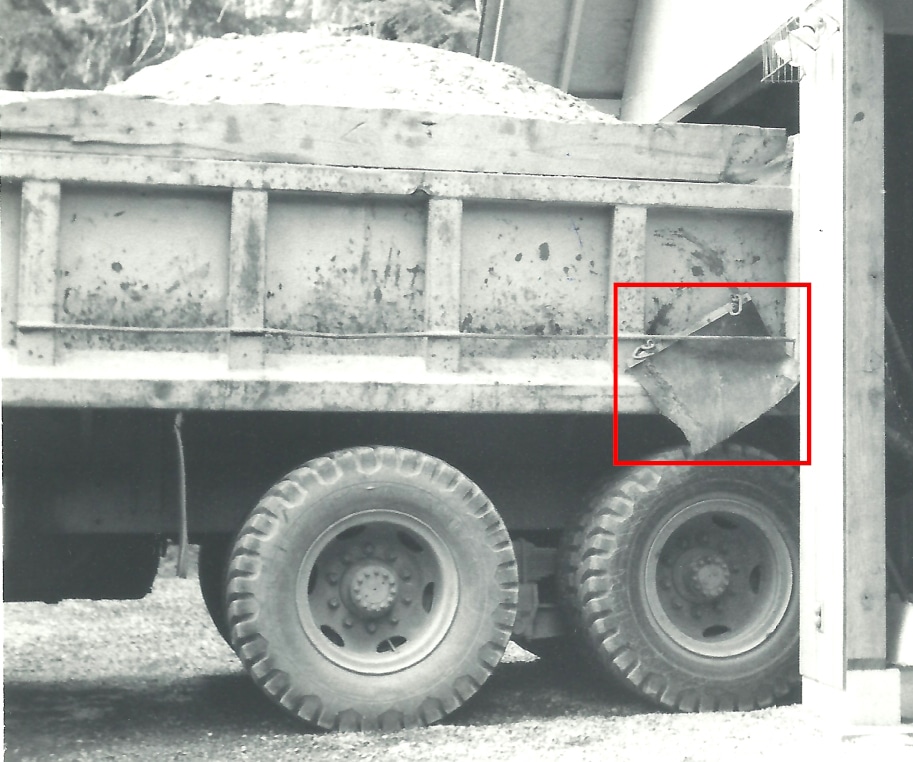

Now, just so there’s no misunderstanding, whoever that was in the Spadoni Brothers dump truck who was given the warning ticket for no mud flaps (on I-5 through Tacoma) did in fact have them, and they were hanging on the back of the truck when the State Patrol pulled it over on an off ramp. They just weren’t hanging exactly where they were supposed to be hanging. It took me … them only one minute flat to put them where they belonged.

Somebody who drove dump truck for Spadoni Brothers always had mud flaps on the truck, but they weren’t always hanging where they were supposed to be. They had to be removed from behind the rearmost tires when unloading hot asphalt, otherwise they would be torn off by the rollers on the paving machine. They were safe when tucked behind the foot rail along each side of the dump box. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

The most corrupted version of Spadoni I’ve ever seen is Adpmo. I can’t even begin to guess how that happened.

New business

People are most often the subjects of Gig Harbor Now and Then. Once in a while we veer away to something less volatile and more predictable than humans. Our next column will be one of those times. But people still play a role in the column, and are a significant part of the story.

Dendrochronology is the study of tree rings. Most people know that they show how fast a tree has grown and how old it was when it was cut down. But they can also tell a lot more than age and growth rate. They can also tell us … well, we’ll save that for next time. Instead, we’ll just say that Gig Harbor Now and Then No. 44, on Jan. 27, may be the best one so far. It takes a very close look at what the insides of trees can tell us about the past.

So, naturally, the local history question of the week has to be:

What can the inside of trees tell us about local history?

It’s a pretty broad question, but we’ll narrow the answer by using a specific tree as an example. A caution to the squeamish: it involves a post-mortem examination.

Item of Mystery

Tonya Strickland is still the only one who has correctly identified the Gig Harbor Now and Then Item of Mystery, but she remains ineligible for the winning prize of 19 Marlboro cigarettes. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Having still not been made aware of a correct identification of the Gig Harbor Now and Then Item of Mystery, here is yet another clue:

During typical use, it experiences a wide range of temperatures, from extreme cold to very hot.

Next time

In the next Gig Harbor Now and Then column, after we see a tree spilling its guts, we’ll set up a new question. The subject will be telephones. No, not the kind that now rules every aspect of your life, and sounds off at every inopportune time, making you feel like a schmuck for not turning it to Silent when you walked into the church, wedding, funeral, doctor’s appointment, theatrical play, etcetera. It concerns the Gig Harbor Peninsula’s first telephone system. And we don’t make you guess what year it became operational. We tell you outright. The question concerns something else. Something more difficult, of course.

— Greg Spadoni, January 13, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.