Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Local humanitarian Packer spared by famous villain

Among the more curious things to be found in history are chains of influence. When researching the past, sometimes you discover the most unexpected ways in which people or events affected the playing out of other, sometimes much later, events. Each influence in a chain of events, no matter if major or minor, becomes a link in the chain. Oftentimes, the closer you look, the more links you find. The more you find, the longer the chain.

This week we present just a few links in two chains of undetermined length. They are specifically chosen to be of exceptional interest, of course, because we aim to please all 10 of our regular readers.

A civic-minded war veteran

William H. Packer was a Peninsula resident for over 30 years, beginning just before the turn of the 20th century. Upon arrival in this area, he first lived in Glenwood, then Burley, before moving to Gig Harbor in 1920, several years after his wife died. He had a varied background, having been a soldier, electrician, machinist, postmaster, farmer, and in retirement was the largest stockholder in the Gig Harbor Community Hall. He was active in the affairs of the community nearly to the end of his 92 years.

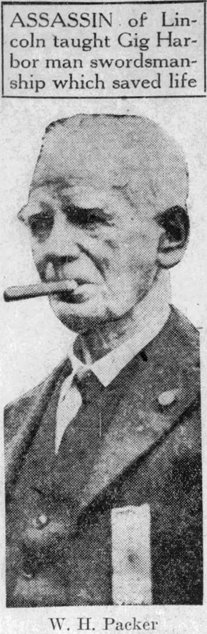

William Packer was a tireless supporter of the communities in which he lived. This photo accompanied his obituary in The News Tribune in 1937.

Packer was so involved with helping others with whatever problems they may have had that when he, at the age of 75, fixed an electrical malfunction at the local weekly newspaper’s printing office, the editor began his note of thanks in the next issue with, “W.H. Packer, whose chief mission seems to be driving trouble from other people’s door …”

The Civil War veteran was an active supporter of the greater Peninsula community in voice, deeds and financially. He regularly attended public meetings, plays, dances and holiday celebrations, marched in local parades as a drummer, supplied music to community halls with his hand-cranked phonograph, gave money to worthy causes, and was well known for treating various groups of kids and adults to five-gallon buckets of ice cream.

Throughout his years on the Peninsula, he influenced many people in a variety of good ways and to varying positive degrees.

But what influenced his life’s course? What specific events or experiences allowed him to survive to an advanced age and help countless others during that long life?

His encounter with one man is key to a large part of the answer. That man was perhaps the most unlikely to have had such a positive influence on a young William Packer, given that he would have the opposite effect on another man, several years later.

A life-saving lesson

As a youth, Packer had a certain fascination with the theater, and aspired to become an actor. It was in the northeastern United States in 1859 while performing in a stage production of the Alexandre Dumas novel “The Three Guardsmen” (more popularly known today as “The Three Musketeers”) that the 14-year-old learned the art of swordsmanship. He credited that skill, and the man responsible for him learning it, for saving his life in one of the many battles he fought in during the Civil War.

As a Union infantryman in the thick of the Battle of the Wilderness, one of the five worst engagements of the war in terms of combined casualties, Packer found himself afoot without a rifle. In the chaos of combat, much of it hand-to-hand, as bullets flew, cannons barked, men yelled in fear and screamed in agony, the young soldier was charged by a mounted Confederate cavalryman wielding a sword. Thinking fast and having no alternative, Packer quickly drew his own sword and thrust it towards the horse of his attacker. The animal reared up, placing the rider in the path of a bullet that would have otherwise passed harmlessly over his head. Mortally wounded, the Confederate lost his grip on his weapon as he fell from his mount. The enemy sword, its descent powered only by gravity, struck Packer on the head as it dropped to the ground.

Though it could’ve been fatal, had the horseman been in control of the long blade as it landed on Packer’s skull, his wound was not serious, and he lived to tell the tale many years later.

“I had learned through constant stage practice to draw my weapon quickly and handle it vigorously,” he told “The Tacoma Daily Ledger” in 1927. “The rebel was almost on top of me before I saw him. If I had not been able to arm myself instantly, he would have cut me down before I had my sword halfway out of the scabbard.”

As he related to the newspaper, his swordsmanship mentor of sorts did not teach the young thespian the art as a favor. Quite the opposite. According to Packer, he had to learn how to defend himself from the man. “[He] was a surly, venomous sort of man,” Packer told the newspaper. “On the stage he showed absolutely no consideration for his fellow actors. In “The Three Guardsmen” he would have run his sword through us with no compunction at all if we had not been able to defend ourselves. He was generally disliked.”

Obviously, it was not out of concern for the boy or an urge to be helpful that led the man to force Packer to learn how to defend himself with a sword. The result, though in the teenager’s favor, was simply a byproduct of an ill-tempered man who cared about no one but himself. Only unwittingly and ungenerously did he affect the life of W.H. Packer for the better, allowing him to survive the Civil War and spread kindness and a helping hand to the residents of the greater Gig Harbor Peninsula.

A notorious figure in history

The man who indirectly saved W.H. Packer’s life by compelling him to learn effective swordsmanship also did other, more consequential, things. The result of his final insult to humanity was a series of infinitely larger links in a major chain of world history. The “surly, venomous sort of man,” as William Packer described him, would ultimately change the course of U.S. history in 1865 by assassinating President Abraham Lincoln.

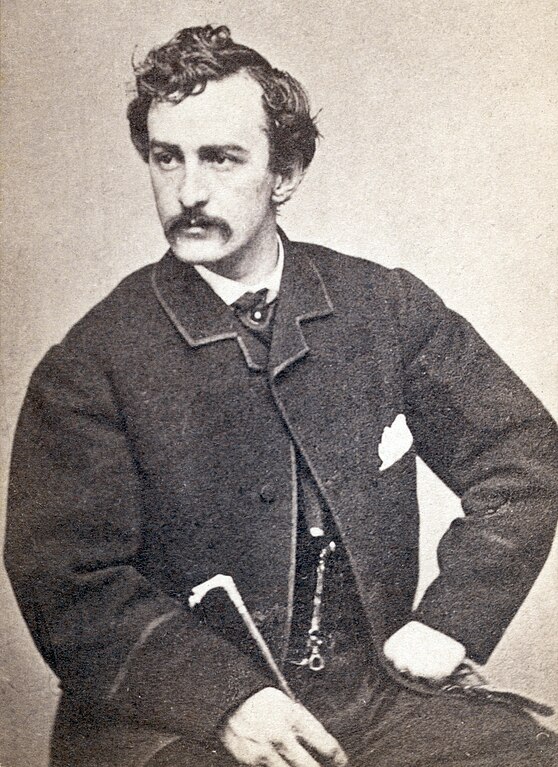

In a bizarre twist of history, President Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, had a very unlikely positive influence on the greater Gig Harbor Peninsula in the early decades of the 20th century. Photo by Alexander Gardner.

John Wilkes Booth, one of the most notorious murderers in all of history, played a pivotal role — though not in a noble way — in William Packer’s survival of the Civil War. It is one of the mind-boggling convolutions of history that none of Packer’s later kindness to the people of the Gig Harbor and Key peninsulas would have occurred had Booth not been such a rotten, self-centered, evil creature.

Not every link in a chain of history is an admirable one. But the relative quality of a link isn’t an indication of where the chain will ultimately lead. John Wilkes Booth’s two chains of history noted here were both rooted in self-serving madness, yet one led to positive links as history progressed, while the other resulted in links of death, destruction and years of national turmoil.

The positive chain, however, couldn’t have become so without William Packer’s influence of benevolence and genuine concern for the well-being of his fellow man.

In spite of sometimes overwhelming odds against them, individuals can make a positive difference in life and in history. William Packer proved it, and the greater Gig Harbor Peninsula was the beneficiary.

A few examples

Here are but a very few examples of William Packer’s involvement with the Peninsula’s civic affairs, all from his later years:

- During World War I, in August 1918, he pledged to donate $10 a month to the Red Cross for the duration of the war, and also, in celebration of his 73rd birthday, treated the local Red Cross ladies to a “five gallon can of ice cream.”

- He played Santa Claus at the Burley Library Hall in December of that same year.

- In 1920 he treated the last meeting of the year of the Burley PTA to five gallons of ice cream. He was a supporter of the Chataqua program of entertainments in Gig Harbor, and marched and played drum in the Burley Sunday School Parade and other events. Late in the year he sold his Burley place and moved to Gig Harbor after attending the National Convention of the Grand Army of the Republic (a Civil War veterans association) in Indiana.

- In June, 1921, he treated all the kids participating in the Gig Harbor Flag Day celebration to ice cream.

- In 1923 when the local Community Chorus sang on a Tacoma radio broadcast, he treated the 30 singers to ice cream. Also in 1923 he played his phonograph at the Gig Harbor Community Hall to provide dance music for the youngsters; gave money to the Gig Harbor Methodist Episcopal Church song book fund, which amounted to one-quarter of all the money raised; played his phonograph at the Burley Valley Fair in the fall, and at the Gig Harbor Community Hall on New Year’s Eve.

- He played his Victrola at the Gig Harbor Community Hall for kids in 1924.

Looking forward

The subject of our next column, on July 29, will be the remnants of Peninsula logging railroad grades from more than 100 years ago. The question of the week will concern the location of a certain logging railroad crossing.