Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | How Leonard Bolton ended up on the naughty list

Our last question of local history was a simple, rhetorical one, with no setup:

What did Leonard Bolton of the Key Peninsula give to his mistress on Christmas Eve, 1941?

The answer is in the following story about a memorable Christmas Eve that took place on both the Key and Gig Harbor peninsulas.

Huckleberry Bolton

The Great Depression was slow to hit the rural Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, but when it did, it hit hard. As the economy slowed to a crawl, prices began to fall, and wages soon followed. The deflationary spiral was brutal, and almost no one was spared.

The local huckleberry industry, which was sizable, suffered along with everyone else. Falling prices meant that people who depended on the fall harvest were in a terrific bind. By 1933, buyers were paying only three cents per pound, 40% less than in previous years. Desperate to make a living wage, many local huckleberry pickers decided to organize and demand that buyers pay five cents.

Labor movements don’t happen organically through the rank and file; they need leaders. In Vaughn resident Leonard Bolton, the local movement found a part-time huckleberry picker with labor organizing experience. He had been deeply involved with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in its efforts to unionize timber workers in southern Oregon 10 years prior. He had also been arrested for his involvement, on a charge of “criminal syndicalism.”

Though he was only one of the leaders of the efforts to organize the Washington Huckleberry Pickers association on the Key and Gig Harbor peninsulas, Bolton received the most publicity. Apparently possessing the opinion that fear and intimidation were valuable tactics in achieving the group’s goals, he found himself in trouble with the law for employing them. He was arrested for firing bullets into the car of a picker who didn’t want to join the new organization. The charges were dropped for lack of evidence.

Ultimately the Washington Berry Pickers did not receive their desired five cents per pound. The price remained at three cents.

Breaking social rules

Leonard Bolton made a habit of sorts of breaking rules, both legal and moral. In 1941 he entered into a torrid love affair with a woman who was not his wife. He met Grace Martin through a Works Progress Administration job headed by her husband, Merle. He became friends with both, eventually taking favor to Mrs. Martin.

Bolton had married divorcée Doris Bond, 10 years his senior, in Klamath Falls, Oregon, in 1923. But in 1941, after 18 years of marriage, the 51-year-old found the opportunity to take up with 33-year-old Grace Martin too enticing to turn down. They were not open about it, going to great efforts to conceal their affair. After all, they were both married, and didn’t want to be hassled by the moral standards of the day. They would meet secretly on little-used logging roads, enjoy each other’s companionship, and return to their spouses.

Deliberate accidents happen

December of 1941 brought serious changes to their lives, not simply because of the United States entering World War II. As they had so many times before in the previous months, on Christmas Eve they met in the Horseshoe Lake area, closer to her house than his. It was the season for giving, and Leonard had a special present for Grace.

On a desolate dirt road, in the quiet solitude and cover of a second-growth forest, he surprised her with his gift: A sharp blow to the head with a hard, blunt object. One newspaper report later said it was a hammer, another said it was a jack handle from his truck. Whatever it was, it knocked her cold.

As if his first gift to Mrs. Martin wasn’t enough, Bolton had one more. In a further act of cold deliberation, he laid her unconscious body crossways on the unpaved road and ran over her with his truck, loaded with firewood, just to make sure she was dead.

The depths of evil can be unimaginable to the average soul, and Leonard Bolton was about to demonstrate that his was even deeper than the brutal act of murder. Thinking he had finished her off, he set about using her death to become a sympathetic figure in the eyes of the community.

He loaded Grace’s barely-breathing body into the cab of his truck and raced off to Gig Harbor to spin the murder into a tragic accident, with him as an innocent victim too.

At the small Gig Harbor Hospital on the water side of Wickersham Drive (today known as Soundview Drive), overlooking The Narrows, Dr. Arthur Monzingo quickly evaluated the dying Mrs. Martin as Bolton told his tragic tale to Pierce County Deputy Sheriff Paulson. He admitted their love affair, but fabricated the cause of her injuries.

“I had a date with her and was on my way to meet her,” he was quoted in the Dec. 27 Seattle Times as having told Paulson. “I ran over something in the road and went back to see what it was — and it was Mrs. Martin.”

It was a terrible, horrific accident, Bolton claimed. Grace’s crushed chest with broken ribs certainly made his story plausible, but Dr. Monzingo noticed something that didn’t fit the narrative: the deep gash in her forehead caused by the hammer (or jack handle). After Mrs. Martin had been loaded onto a ferry bound for Tacoma, where she could get more intensive care at a larger hospital, Dr. Monzingo tipped off Deputy Paulson, and an investigation was launched.

Grace Martin didn’t make it to Tacoma. She died on the ferry before it arrived. On that otherwise festive day before Christmas, her body was returned to Gig Harbor and taken to Perkins Funeral Home near the Gig Harbor Hospital.

Heavy crime and light punishment

After admitting his guilt under police questioning (as reported in the same Dec. 27 article in the Seattle Times), Bolton was arrested and charged with second degree murder. He was convicted the following April. While awaiting sentencing, he filled out his World War 2 draft registration card, giving his mailing address as Lake Bay, Washington, but his place of residence as County Jail, Tacoma. The back side of the card noted that he was 5 feet, seven inches tall, weighed 145 pounds, with blue eyes, gray hair, a dark complexion, and had “small finger on left hand off at first joint.”

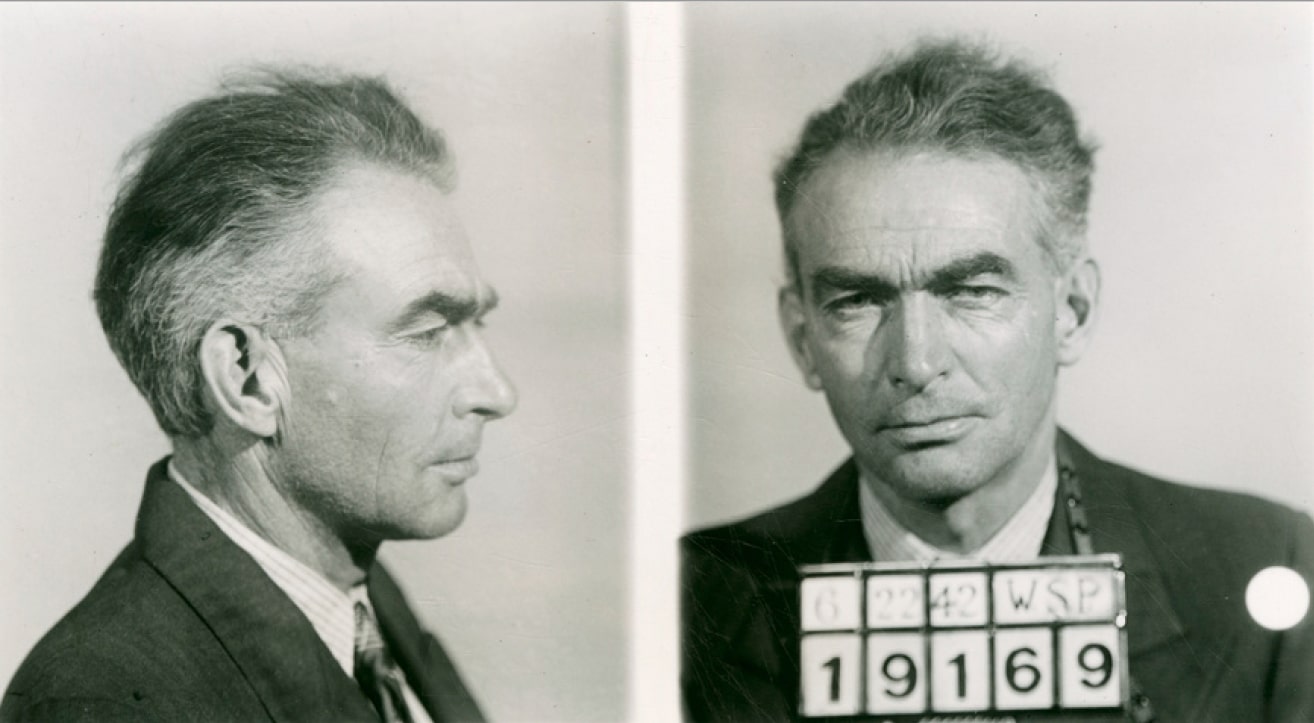

Leonard Jewel Bolton’s 1942 mugshot was found at the Washington State Digital Archives.

Bolton was sentenced to 10 years in the state penitentiary. He served less, and returned to the Key Peninsula to live out his life with his wife, who did not leave him. Apparently she didn’t view adultery or murder as grounds for divorce. They are buried side-by-side in the Vaughn Bay Cemetery.

Doris Bolton rests in eternal peace next to a murderer. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Surplus notes

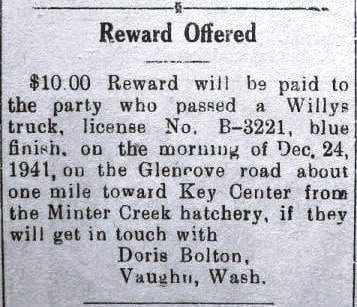

There are almost always bits and pieces left over after a story of local history is written. To keep a narrative moving at a comfortable pace and in an understandable, logical order, it’s often necessary to leave out difficult-to-blend-in parts. But sometimes what’s left out is also of at least some interest. An example from the Bolton story is a small advertisement that ran in The Peninsula Gateway on Jan. 30, 1942.

This advertisement from The Peninsula Gateway was found at the Harbor History Museum.

Doris Bolton was offering $10 to anyone who saw a specific, blue Willys truck at a general location along the Glencove Road on the morning her husband murdered Grace Martin. What kind of information was she looking for? Was she hoping to find evidence to prove her husband innocent? Or was she trying to help prove him guilty?

The strong implication from the advertisement is that Leonard Bolton’s truck was a Willys. But was it really? Or was she referring to a different truck? If so, why?

We will never know.

Hopalong Cassidy

Peripheral information, too, is almost always left out of a story. It’s not pertinent to the primary subject, so would simply add unnecessary length. But some non-pertinent information can be interesting as well. In the Bolton story, it’s interesting to note the participants’ connections to Gig Harbor and the motion picture industry.

Grace Martin’s first husband was Cal Russell, who operated the Pastime Pool Hall in the Novak building in Gig Harbor for many years. They were married in 1927. Her sister, Mabel Austin, was the second wife of Charles Austin, of the Austin Mill, where the Harbor History Museum now stands.

Grace married Merle Martin, an ex-U.S. Marine, in 1936. After her death, he enlisted in an unknown branch of the service, at the rather late age of 43. In 1944 he married former silent film actress and D.W. Griffith darling Elinor Fair. Her previous husband was William Boyd, who played Hopalong Cassidy both in movies and on television. Merle and Elinor were married until her death from alcoholism in 1957.

Errors and fiction

There are numerous errors in contemporary newspaper accounts of Bolton’s murder of Grace Martin. Later versions are even less accurate.

In an act of blatant exploitation of Grace Martin’s murder, on July 29, 1945, The Dayton Daily News in Ohio, published a highly fictionalized story of the case, passing it off as a true story.

On May 26, 1946, The Seattle Sunday Times published an equally fictionalized account of the crime. Timelines, facts, and dialog were largely fabricated. It is in no way an accurate representation of the murder of Grace Martin.

New business

We’re going to have a simple, easy question of local history in this week’s column. We don’t want one of our typically provocative, stimulating, obsession-forming Gig Harbor Now and Then questions of the week to in any manner distract from the normal reverie of the holiday season. Before getting to the simple, easy question of the week, however, we will answer right here and now the unspoken question arising from the previous sentence: Yes, it was typed with a straight face. It shouldn’t have been, but it was. From this end of the keyboard, such bombastic statements are all too common. They no longer un-straighten the face.

The new question involves the Vaughn Library Hall, which has been featured in a previous Gig Harbor Now and Then column.

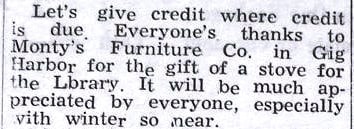

Located in Vaughn, on the Key Peninsula, it is the oldest remaining community meeting hall on either the Key or Gig Harbor peninsulas. Throughout its 131-year existence, it has relied heavily on donated labor, materials, and money for upgrades, upkeep, and routine expenses. In 1952 Monty’s Furniture Company of Gig Harbor donated a heating stove to the library portion of the hall.

This clip, from the Vaughn News section of the October 24, 1952, issue of the Peninsula Gateway, was found at the Harbor History Museum.

The non-provocative, unstimulating, non-obsession-forming Gig Harbor Now and Then questions of the week is:

Where in Gig Harbor was Monty’s Furniture store in 1952?

Item of Mystery

The Gig Harbor Now and Then Item of Mystery remains unidentified (except by Tonya Strickland, who remains ineligible). Photo by Greg Spadoni.

With word of anyone correctly identifying the Gig Harbor Now and Then Item of Mystery not having reached me, I can only assume that no one has done so. That means it’s time for another hint. Or clue. I don’t know the difference between the two, so whichever it is, this is it:

These things have been used all around the world, though probably only in North America today.

Next time

On Dec. 30, we’ll have the answer to today’s simple and easy question. We’ll also have a new question of local history, and it will concern spelling. It probably would’ve been a smoother transition had it immediately followed the Dec. 2 column, which covered spelling bees at local grammar schools, but today’s column, being a Christmas Eve story, is more timely for a pre-holiday slot.

Besides, expecting me to be that organized is simply asking too much.

Greg Spadoni, December 16, 2024

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.