Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Notable scoundrels of the peninsula

The history of every small community has its share of less-than-stellar personalities, which is a fairly benign way of saying thieves, scoundrels, conmen, habitual liars, and sometimes even a murderer or two. Most of the unsavory characters are usually forgotten after a generation or so, and the few that are not are often miraculously converted by researchers of history into upstanding, courageous, pillar-of-the-community types, simply because only their good deeds have been uncovered. This is a story about one of the forgotten ones. He was a resident of Fox Island for a short time over 150 years ago.

Arts & Entertainment Sponsor

Arts & Entertainment stories are made possible in part by the Gig Harbor Film Festival, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Benjamin Pardee

One of the achievements attributed to the versatile and industrious Samuel Jeresich, one of the earliest Gig Harbor pioneers, was the establishment of a dogfish oil business in his first few years in Gig Harbor. Another man announced intentions to do the same in 1871, also in Gig Harbor.

That raises the unanswered question of whether the two were in it together. If it was a joint venture, the partnership did not last long. It was in no one’s best interest to be a business partner of Benjamin Scherman Pardee, for he was more con man than businessman. The story of his business failures has a long tail.

In 1855 Pardee, whose first two initials (B.S.) stood for more than just Benjamin Scherman, joined with other men in a brass foundry business in Connecticut, of which he was the secretary and treasurer. The book “History of the Town of Hamden, Connecticut” summed up the venture by saying, “After five years of folly, the bankrupt estate paid three cents on a dollar, wasting a capital of 60,000 dollars.”

After serving in the Union Army in the early part of the Civil War he made his way west, becoming an agent of the Office of Indian Affairs in Washington Territory. While living in the territorial capital, Olympia, he joined a group that organized The Olympia Branch Railroad Company, purported to be capitalized with $400,000, a huge sum for the times. It seems to have faded away without fanfare.

He then embarked upon his plan to manufacture dogfish oil for use as a machine lubricant. In April 1871, he placed an order with the Oregon Iron Works of Portland for a sheet-iron digester, a necessary part of the oil extraction process. If he did install it in Gig Harbor, as he originally announced, it was there only temporarily.

Fox Island fish oil

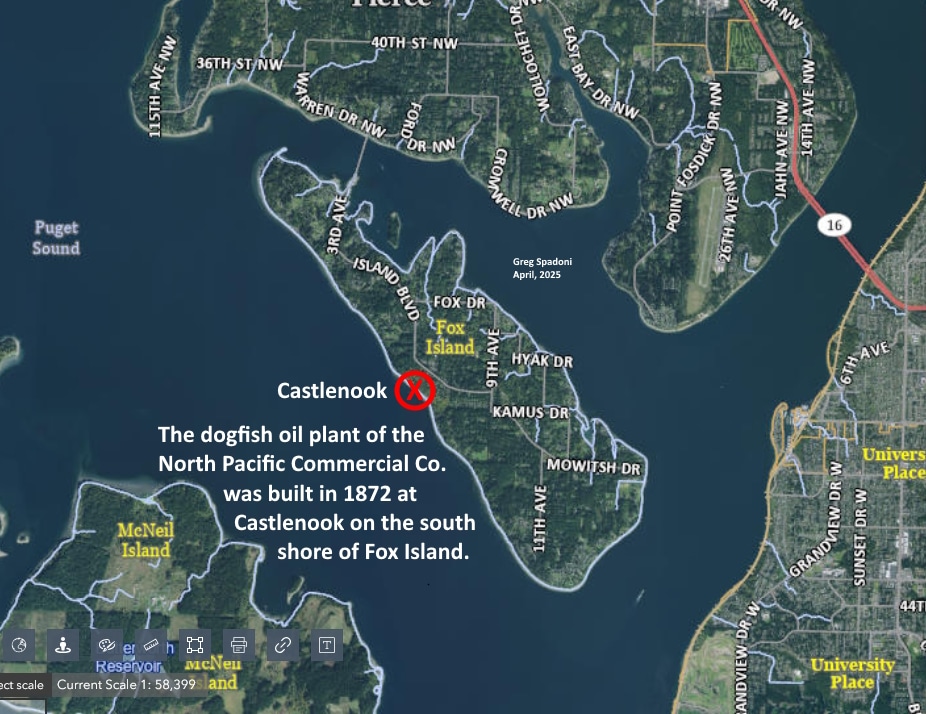

At the beginning of 1872 he organized the North Pacific Commercial Company in California and convinced several San Francisco investors to capitalize the new enterprise with $15,000. He returned to Puget Sound and built a substantial fish oil plant at Castlenook on Fox Island, of which he was the superintendent.

The North Pacific Commercial Co. set up its dogfish oil operations on the south shore of Fox Island, at a spot called Castlenook. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

A visitor described the installation in the Sept. 14, 1872, Washington Standard:

The oil factory consists of a two story building 40×60 feet, with adjacent sheds. In the building is an iron tank or cylinder, holding perhaps eight hundred gallons, a boiler of ten horsepower, a screw press, a small steam engine, an Excelsior mill, and sundry large tanks lined with zink [galvanizing], which were nearly full of oil. The basement of the building is stored with barrels. …Besides the factory, there are other buildings for the employes [sic], and a large tent, in which the family of the superintendent [Pardee] and some young ladies from Olympia seemed to be enjoying their island rustication. … Mr. Creighton, the engineer at Castlenook … reports a daily catch of three or four thousand large fish.

The visitor also described an encounter with Pardee:

We inquired for Col. B. S. Pardee, the Superintendent of the company, and learned he was off with the “trawl” men … Before we left, the Superintendent returned to the island, but while he seemed ready to answer any general questions, we found him very reticent about plans for extending the business, and we did not gain anything by waiting for him, except courteous treatment and a good cigar apiece.

Bon voyage and belly up

Near the end of the year, when production proved to be below expectations, a representative of the company’s stockholders was dispatched from California to investigate. Pardee, having advance notice of the man’s arrival, absconded with a substantial amount of company funds, ultimately forcing the business into bankruptcy.

Although the story, as reported in The Stockton Independent (of California) on Jan. 21, 1873, didn’t mention Pardee’s name, it left no doubt as to who was to blame:

Another enterprise for the development of the resources of this coast has been aided by San Francisco capitalists, and they now mourn over the loss of the invested capital. This time it was not a diamond speculation, but a speculation in oil. Neither was it any of those chimerical schemes which have been suggested by impecunious prospectors and land owners to utilize the substance, which flows in large quantities from various springs in the southern portion of this State, but a legitimate oil speculation, the making of “dog fish oil,” from the livers of those hideous denizens of the deep, which are said to abound in the waters of Puget Sound. The rascally deceiver who this time betrayed the confidence of the verdant and too confiding San Franciscans was an ex-Indian agent, who from long intercourse with the native barbarians, had become only too well qualified to deceive. He organized a joint stock company and called it the North Pacific Commercial Company. Like a wise man having a good thing, he retained a portion of the stock in his own name, and like a shrewd man, which it is now admitted he is, he collected from the other stockholders $15,000 to erect the necessary works, to extract the oil from the livers of the dog fish aforesaid. After having collected this amount of money he wended his way to those northern waters where these canine fish do congregate, and commenced operations. From some cause or other, the San Francisco stockholders became dissatisfied—the flow of oil was irregular—and an expert was sent out to report the cause of the irregularity. The ex-Indian agent, however, being informed thereof, had business farther north, and leaving very abruptly he forgot to leave behind him a large amount of the company’s funds which he had at that time in his possession. The expert of the San Francisco stockholders is inclined to think they have been victimized, and they are now anxiously inquiring the whereabouts of the ex-Indian agent.

Now, we protest that something should be done to protect the citizens of San Francisco from being swindled in this manner. …

The remnants of the North Pacific Commercial Co. were sold on May 13, 1873.

Back in Olympia, The Washington Standard of June 7, 1873, said that the whole enterprise had been “a downright swindle.” It further reported, “It appears, from information furnished the Express, that the North Pacific Commercial Co. has proven to have been a swindle from its inception down to the closing out sale, which recently occurred in San Francisco. Instead of settling the liabilities, as honest people do, they deceived the creditors to gain time and finally transferred everything in the name of the company to B.F. Taylor, of San Francisco, for the mere pittance of $335. Many hundred dollars are due laborers and others on the Sound.”

Having bought the physical assets of the North Pacific Commercial Co., Taylor changed the name to Castlenook Fisheries and relocated the headquarters to Steilacoom Bay.

After bankruptcy, the successor company to the North Pacific Commercial Co. was B. F. Taylor’s Castlenook Fisheries, based at Steilacoom Bay, south of Fox Island. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Election tampering

Leading up to the Washington Territory fall election in 1872, and soon before the failure of the North Pacific Commercial Co., Pardee, again living in Olympia, was accused of forging the signatures of Republicans on a pledge to support a specific candidate for office. Compelling evidence was lacking, and he avoided prosecution.

But there was still that little matter of having stolen his fish oil business partners’ money. Not yet held responsible for it, but perhaps feeling the heat, in January 1873, he moved back east “for health reasons.” Nearly as soon as he arrived in Washington, D. C., he miraculously regained enough health to engage in further forgery, not for political purposes, but for $10 bank notes.

The Puget Sound Dispatch, May 15, 1873, page 1:

“PICKED UP FISH.” — Our late fellow-citizen, Col. B. S. Pardee, was lately arrested in Washington, D. C., under the alias of “Rev. J. Hale Barney,” charged in general with using the mails for fraudulent purposes; obtaining money under false pretenses, and forgery. The specifications are numerous, making a long chapter in the police journals.

Pardee, masquerading as the fictional Reverend J. Hale Barney, had forged the signature of U.S. President Grant’s Private Secretary (equivalent today to Chief of Staff), Gen. Orville E. Babcock, on a series of letters purporting to be a secret fundraising effort to combat voter fraud in certain states. Claiming he, as the fake reverend, was a part of the plan, he asked that $10 be sent to him in the strictest confidence. “This subject is CONFIDENTIAL, and known only to three persons besides the President,” the letter stated.

The real Gen. Babcock was tipped off to the scheme by an inquiry sent by a recipient of one of the letters, and he notified the Treasury Department. Government detectives investigated and caught Pardee red-handed in April 1873. Two other conspirators were arrested the same day.

Avoids prison

Ten months after his arrest, a letter from Pardee’s father was published in The Hartford Daily Courant, Pardee’s hometown newspaper, telling of the forger’s fate:

New Haven, February 16, 1874

Colonel B. S. Pardee is in the Hospital for the Insane in this state, where he has been since September last, with but small prospect of his recovery. His malady has been of long standing, although a person not previously acquainted with him would not discover that his mind was disordered in any ordinary intercourse with him. The physician in charge at the hospital prefers to have him receive no letters and to hold no correspondence with any one whereby past events and occurrences in his life will be kept in mind; and accordingly I have not written to or seen him since he was placed in the hospital.

In spite of the pessimistic prognosis, Pardee was eventually released from the insane hospital. In a move that prompts credible doubts about him having recovered his sanity, he spent most of the rest of his career as a newspaper editor on the East Coast.

Benjamin Pardee died in New York City in 1900 at the age of 70. Predictably, his obituary gives the impression that he was a great guy. It doesn’t mention any of his troubles with the law.

Next time

Our next column, on May 5, will be another either/or choice. It will either be my next contribution to Tonya Strickland’s Behind the Finds series, or will return to questions of local history.

The holdup on my next entry in the Behind the Finds series is the typically futile wait for responses from descendants of the subjects of historical research. Currently there are two unanswered Facebook messages by Tonya, two paper letters and one email outstanding by me, and one letter returned as undeliverable.

The internet has lots of addresses for lots of people, but it rarely tells you which ones are current. This letter was returned last week as undeliverable due to “No mail receptacle, unable to forward.” Google Maps shows a perfectly decent house at the address, but sure enough, there is no receptacle atop the mailbox post.

When contacting descendants, it’s easy to imagine they’d be thrilled to be presented with (in this case) the opportunity to see photos of their departed relatives (their fathers) as teenagers goofing off at a friend’s house in the 1930s in exchange for the answers to a few general questions. But experience has proven many, many times that the overwhelming majority of contactees never respond. About two-thirds, in fact.

That means the most optimistic expectation from the six attempts noted here is only two possible responses. The most realistic expectation is zero. Another two weeks will tell the tale, although the lack of any response after the first two weeks pretty much sums it up already.

If the May 5 column returns to questions of local history, it will leave the dogfish of today’s story behind in favor of salmon. With that clue, it should be no surprise that the topic concerns Gig Harbor’s commercial fishing fleet (as opposed to, say, the printer of canned salmon labels). The two questions will center on certain people who worked on one of the boats. Whether they are interesting questions remains to be seen. But even if they’re not, the answers sure are interesting.

So, even if you find the questions uninspiring, don’t be discouraged. Be sure to read the answers on May 19 (unless it gets bumped to June 2). These are the very words you’ll speak out loud after reading the answers: “Boy, that was worth reading!” And about three-quarters of you will follow that up with, “Really interesting!” The rest of you will simply think it.

—Greg Spadoni, April 21, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.