Community Health & Wellness

Q&A | A conversation about the many forms of domestic violence

Reader warning: This article discusses many forms of intimate partner violence, including emotional, psychological, and financial manipulation, as well as some discussion of physical violence.

Health & Wellness Sponsor

Health and Wellness stories are made possible in part by Virginia Mason Franciscan Health, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Nadia Van Atter is the assistant director of the Crystal Judson Family Justice Center, a service center run through the city of Tacoma and Pierce County to help people living in intimate partner domestic violence situations.

Read our 2023 series on local resources for victims of domestic violence here.

In recognition of Domestic Violence Awareness Month, Carolyn Bick sat down with Van Atter to talk about the many forms domestic violence can take, and how loved ones can help someone they fear may be in such a situation. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Gig Harbor Now: How did you come to do the work you do? If you can and would like to share, has domestic violence affected your life personally?

Nadia Van Atter: I’ve been doing this work for about 15 years, at this point. I knew that I wanted to do something that involved working with women and children that had experienced trauma or crisis and didn’t quite know what exactly where I wanted to do that. I started out with one of our partner agencies, Our Sister’s House.

They had a grant that was just around working with crime victims and had a connection there through a friend that said, ‘Hey, you might like this work. You should apply. When that grant ended, it got shifted into domestic violence, and it turned out that was a really good fit.

I hope that answers the first part. And I will say, domestic violence impacts all of us. Whether we ourselves have been survivors of it, we all know someone who’s experienced it.

I think about really important women in my life, who were very instrumental in helping raise and support me. I don’t think it was until I was an adult that I think back on conversations that my parents had about their relationships and what was going on that it dawned on me that that probably was a domestic violence relationship in some form that was happening. So, it is something that I think about — just people in my life that have experienced it.

I think that’s one of my motivators to show up — helping support people in my community.

GHN: What kind of work do you do with the Crystal Judson Family Justice Center?

Van Atter: The center works to support survivors of domestic violence, but specifically intimate partner violence [IPV] — the dating relationship or spouse portion.

The Family Justice Center is actually an international model, at this point. It’s about co-location and collaboration. To be considered an FJC, you have to have co-location with law enforcement, prosecutors, and community-based services. And everything that’s on our community-based side is confidential, outside of the standard mandated reporting.

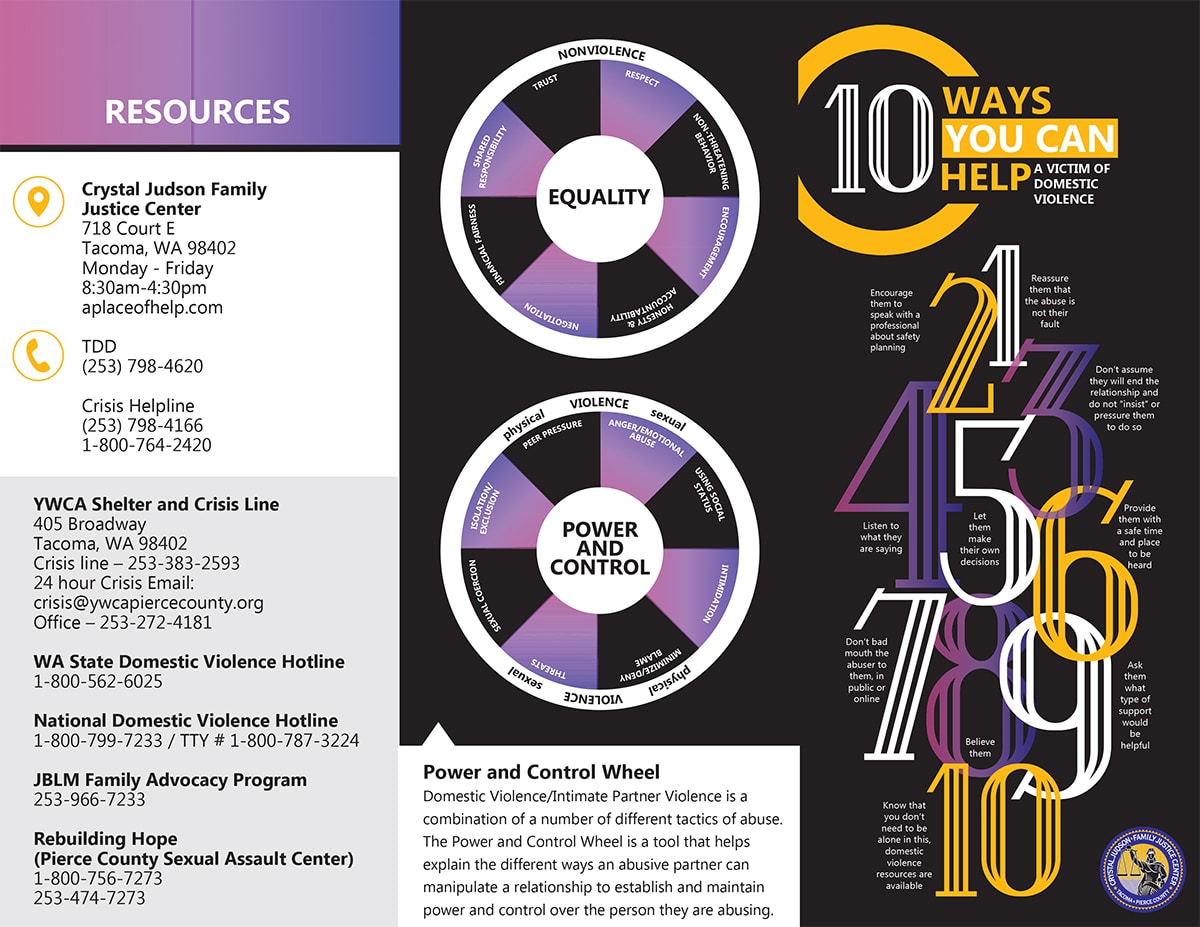

A brochure from the Crystal Judson Family Justice Center includes resources and information, including a crisis helpline.

We’ve got multiple partners coming from different areas in one location. Our community side is working with survivors wherever they’re at in their journey, which could be, ‘I don’t know if I’m experiencing domestic violence,’ to, ‘I’m ready to leave,’ to, ‘I know that my partner’s behavior is not okay, but I don’t know that I’m ready to leave or feel like I can make that move right now.’

Wherever someone’s at, we want to try to meet them and we want to do it with a trauma-informed, survivor-centered focus — the idea of understanding that people have a variety of influences and a variety of things going on in their life, and really just giving them space to talk about safety and resources and options, wherever they’re at.

We have seven different programs that are designed to disrupt the different spokes of the Power and Control Wheel, which is at the heart of domestic violence — that imbalance of power.

GHN: I really wanted, in this interview, to focus on the more “subtle” forms of domestic violence, particularly emotional abuse and manipulation. I think that when people think of domestic violence, they still only think of physical violence. But that’s not the case.

Van Atter: You know that picture of the iceberg, where you see the tip of it and then you see a waterline and then the gigantic one underneath? I always use that as a visual when I lead into DV education. It works so well, because, like you said, when people think of domestic violence, they really think of what you can see, right? Like, I am walking around with a black eye — something very visual, versus all of those behaviors that are underneath the waterline.

What’s hard is how we define domestic violence within the system. As a society, it’s the illegal things versus all of those behaviors that systematically isolate a survivor from their resources and options, and make them reliant on the person causing harm. It is really all of those underlying behaviors.

Survivors will often say, “People would believe me or be willing to help me, if there was physical violence and they could see it, but they don’t understand those other parts.”

And I will say, as a provider hearing that, that just makes my heart hurt — that we’re not willing to take a step back and look at all of these other things, which cause fear. All of these things lead into each other.

That when you look at the Power and Control wheel, which was developed in the 70s by providers that worked with survivors and folks causing harm. One of the things that you see is how all of these different spokes really lean into each other. It’s not this one isolated incident.

You have things like emotional abuse, which is really making someone doubt themselves and pick them apart and really warps their sense of self. And I think a really good way to describe that is like looking in a funhouse mirror.

If I walk into a funhouse mirror, I look around and I say, “Well, I look ridiculous, but that’s not what I look like.” And then I go home and I look in a regular mirror and I see what I look like.

When you’re in an abusive relationship, it’s like you’re living in a funhouse mirror because that’s the only mirror that’s getting reflected back to you. And so, over time, that’s what you start to think you look like, which is why family and friends play such a huge role. They are offering that chance to show that real life mirror, — “No, you really are doing an amazing job. You’re doing all these other wonderful things.”

And then you have things like isolation, which can happen in really blatant ways, like taking a survivor’s car keys or purse or wallet or bus pass or physically preventing them from leaving. Those things that we really clearly think of.

But you also see this in much more manipulative ways.

If every time my partner goes out to spend time with their family or friends and I’m just constantly blowing up their phone, and then when they get home, I’m picking a fight and there’s a big explosion. After that happens so many times, they may feel like it’s not worth the emotional roller coaster and exhaustion and that emotional safety of going out.

And what that does is that gives the abuser the chance to say, “Your family and friends don’t like hanging out with you. They stopped inviting you to do things. I told you they didn’t care about you.”

You have things like financial abuse, which is, again, the really blatant things that we think of: Controlling the credit cards or the checkbook or not giving someone access to money.

But we’re also looking at this in broader terms than we used to years ago. What if the person causing harm is limiting someone’s ability to build credit? Or maybe they’re putting all of the credit cards in the survivor’s names and then sabotaging and destroying [the survivor’s] credit.

How do you get into new housing if you have no credit or you have a terrible credit score? What happens if the survivor is coming from a family that doesn’t have the finances where they can, you know, co-sign on an apartment? Or what if the abuser has isolated them from their support network? How do you get into housing? Housing is so expensive in our county.

And then you have things like using kids, which could be, “If you leave me, I’m going to call the police and say you kidnapped the kids.”

Now as a provider, I know that it’s more complicated than that. You can’t just do that. The survivor has rights to their kids. They can take the kids and leave.

But again, if you look at how all these things lean into each other, you have someone who is continuing to tell you you’re worthless. You can’t do these things. They’re isolating you from family and friends. They’ve controlled the finances. Maybe they’re using physical and sexual violence as well.

And then you hear, if you take the kids and leave, I’m going to call and say you kidnapped them and you’re never going to get to see them again. That’s a terrifying thing to hear.

And so you see all of these pieces, which again are not necessarily considered illegal. They’re not the tip of the iceberg. It’s all of those behaviors underneath. I mentioned this at the beginning of this question, but it’s really about systematically isolating someone from their resources and options.

And so kind of pulling these different pieces apart, because when someone’s experiencing this, it’s not one isolated incident. It’s all of these things working together to limit a survivor’s options and resources. And then if you look at systems and all of these other pieces, the coercive control power and control wheel really amplifies that.

Nadia Van Atter, assistant director of the Crystal Judson Family Justice Center

GHN: I also wanted to definitely focus on something that I don’t think is really super well-covered, at the moment. Helping people in domestic violence situations is not sort of a “one size fits all” umbrella. Are there different ways you reach out to folks of different cultural backgrounds, or the way that advocates speak with them, or even straight down to who calls them to try to help?

Van Atter: Because domestic violence affects all communities, what we see is it’s going to look slightly different in different communities, and different communities are going to have different likelihoods of reaching out to formalized services.

And then within those different communities, you also have individuals that are navigating things in a different language or have communities that are navigating systematic racism and things like that.

One of the things that we do is we try to make sure that our team is engaged in ongoing training around working with different populations and groups of people. We try to ensure language access.

That’s such an important thing. We know that sometimes folks may engage with us initially in English, but that’s not the language they feel most comfortable in, or feel like they have the specific words to explain things.

We have bilingual and bicultural team members. We have one in Spanish, one in Vietnamese, and one in Cambodian. Our supervisor is fluent in Arabic, Swahili, and Somali, and she’s got that cultural piece, as well. We work to train our team in general so that all of us can work with folks, but we do acknowledge that someone may feel more comfortable being able to speak with someone in whatever language they’re most comfortable in who has that cultural knowledge.

[We also lean] into partnerships where that is their focus. [The Korean Women’s Association] KWA is one of our on-site community partners. Our Sister’s House is another one of our on-site community partners. They are a small [domestic violence] DV agency in Tacoma. While they work with all survivors, they specifically focus on providing culturally specific care for Black and African-American survivors.

GHN: How can a person in a domestic violence situation recognize that they are being abused?

Van Atter: That’s a hard one to answer. I would pivot to start with, if we identify these signs in a loved one, I think just saying like, “Hey, I’ve noticed some things and I really care about you and you deserve to be safe.”

Because sometimes we’ve got folks that come in that say, “I don’t know why I’m in here, but my sister or my pastor or my cousin or whoever told me that I need to come talk to you.”

Oftentimes, abusive behavior is going to start really subtle and kind of slowly amp up. It’s going to start with those things that make you feel a little uncomfortable, kind of makes your stomach feel weird, and then just slowly amp up because it’s pushing those boundaries back little by little. Sometimes people don’t realize it, until it is that more extreme form of violence. But at that point in time, you’re more invested in the relationship where it can be harder to leave.

So, I think, as family and friends, if we see these things, being able to pull that person aside when you know that it’s safe and just say, “I’ve noticed some behaviors and I’m unsure about those, but I care about you,” [versus] “I am going to sit you down and you and I are going to have a really deep conversation and I am going to grill you.” Don’t do that. That’s not helpful.

I think pinpointing when does someone realize it can be really hard, because those are such individual stories.

GHN: So there is also, from what I understand, a culture of shame around domestic violence, married with the feeling of, “Who’s going to believe me, anyway?” I think that that really, at least from where I sit, seems to really hamper people coming forward.

Is there a way that somebody can sit down and talk with a person about this, without saying “domestic violence” at all, and potentially direct them to resources without making them feel like, ‘Oh, I’m going in for this big thing,” because that can be really scary?

This has happened more than once, but your question made me specifically think of this. I remember someone coming in one time, and at one point during the conversation, they said, “I don’t even like you using the term ‘abusive partner,’ ‘abuser,’ because I don’t think of them that way.

It was kind of this moment in my head where I had to shift around how we even have these conversations, because that is a really hard thing to hear.

Statistically, if we look at domestic violence and how high those numbers are, it means we know somebody who’s experienced it. And if we know someone who’s experienced it, we also know the person causing harm. Realistically, we’re going to know both parties.

We need to not just be talking about what unhealthy relationship traits are, but what are healthy relationship traits, so that we are socializing people of what is healthy. We can catch these unhealthy things earlier on, so that it becomes more of a conversation about how do you show up and be a healthy and supportive partner jointly in a relationship versus just saying, “Your partner’s being abusive.”

And I think when we’re having conversations with people that we think might be experiencing these behaviors, I think switching it to talking more about behaviors versus that person is [important].

Sometimes, as a loved one, my initial response may not be as supportive as I want it to be — “That person is so terrible. How could you be with them? They’re awful.”

That’s going to then put the survivor in the position of feeling like they have to defend that person versus if I’m keeping it focused on, “I care about you and you deserve to be safe. I noticed some things that made me unsure that your voice is being heard in that relationship.”

The person causing harm, those behaviors are on them. I want to be very clear. They are the ones that are responsible for that. But as loved ones, if we go in [and say], “I’m so angry at this person and I want to do X and Z,” then that’s putting the survivor in this weird space of having to defend.

But I think that knowledge piece and people genuinely learning about those dynamics can help shift that victim-blaming piece. Because how are people going to come forward if they’re going to be shamed for experiencing this, something that is not their fault?

It is not the survivor’s fault. They are not the one causing the harm. They are navigating trying to stay safe.

Leaving is not this easy, flip a light switch and it’s completely over and everything is perfect and fine. These abusive behaviors have such long-lasting impacts that really impact someone’s ability to make decisions, even when they’re in the process of leaving, even after they’ve left.

Domestic violence is one of those things that thrives in silence. It happens behind closed doors. It is normal that survivors may feel that shame, but they shouldn’t feel that shame.

[If someone discloses] that domestic violence is going on and if you know both parties, if the first thing out of your mouth is, “Oh my gosh, I never would have guessed! Your partner seems so amazing. I don’t believe you” — and you may not mean those things — if that’s the first thing that comes out of someone’s mouth, that’s reinforcing all of that abusive behavior — “Nobody’s going to believe you. Nobody cares. This is on you.”

If the first response is, “Oh, I never would have guessed,” that’s just reinforced that abusive behavior and is going to reinforce that shame that that survivor may feel and the idea that no one may believe them.

GHN: So, lastly, I wanted to know: What are the most difficult and what are the best things about your job?

If I put on my management and assistant director [hat], I would say a hard thing is funding, continuing to say, “This is why you have to fund these things.” I would love it if I didn’t have a job because there was no more domestic violence and we genuinely didn’t need these services. But the reality is, they’re needed.

In my management assistant director role, the part that I love is partnership-building and getting to see the difference that our agencies and other agencies make in the community. No one agency can solve it all.

When I have my advocate hat on, sometimes, it can be really hard to hear stories and know that resources may be limited and that maybe I am unsure what that client is going to do when they go home.

This can be a hard thing to say, because it’s not my role as an advocate to make decisions for someone. It’s up to them. My job as an advocate is to talk about safety and resources and options and provide them support wherever they go.

I will say in my advocate [role], one of the best parts is helping people feel empowered and helping them feel like they have resources and options available, so that they can figure out what is the best next steps for them. We had a former front desk worker who would always say that she would see people come in and she would see how scared they were and how nervous they were to come in and just so unsure.

And that what she loved about her job is she would get to see them afterwards coming out looking like a different person. She was like, “I could see that they had hope on their face.” She would talk about how they were coming in kind of hunched over or [seeming] like they were trying to take up as little space as possible. And she would see them walking out with hope.

People in need of help in Pierce County can contact a number of organizations. They are listed below, and some have emergency escape or safety exit buttons. Please note that this does not mean that websites visited will not be recorded in a browser’s history. It is much safer to access such webpages in either a private browsing window or via computers in a community space, such as a library.

Crystal Judson Family Justice Center

Korean Women’s Association (KWA) (no emergency escape button)

Mi Centro (no emergency escape button)