Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | The dumbest way to kill a shark

Old business

Regarding the answer given in our last column, concerning the location of the Gig Harbor post office, Mark Watland posted on the Gig Harbor Now Facebook page that he had found online a date of 1952 for the post office having moved from the north end of town to the west side. That is one year later than the date we gave. Our information came from a January 1951, issue of The Peninsula Gateway.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

It is because of such discrepancies that we always try to use primary sources for our questions and answers. But that doesn’t mean we always get it right. By all means, if any reader suspects we’ve made a mistake, let us know. After all, we’re trying to correct errors of history, not make them.

On the topic of citizens’ input to the future use of both the Peninsula Gardens property and the bare lot that is The Village at Harbor Hill, I’m not a member of Facebook, so can’t contribute my excellent suggestions on the Gig Harbor Now Facebook page. But I’ve got this column, and feel compelled to weigh in here.

Obviously, the best use for the Peninsula Gardens site is as an auto wrecking yard. It’s nothing more than a simple matter of practicality. Given its relatively central location, it would make a convenient source of discounted auto parts for many local residents. After all, you can’t buy used brake drums at Trader Joe’s. While I don’t fault the grocer for that, the point is that you can already buy groceries at several other places in town. Wouldn’t it make more sense to diversify the retail goods available than to concentrate them?

Another benefit to a wrecking yard would be that the stainless steel razor wire atop the chain-link perimeter fence would never tarnish, looking brand new year after year. And snarling junkyard dogs are always fun to taunt through the fence … until one of them gets out, anyway.

An ideal use for the undeveloped parcel that is The Village at Harbor Hill would be a pork farm.

Not a slaughterhouse, just a farm.

It would be like having a Peninsula zoo. People could enjoy watching pigs grow from immature swine to dinner ham. Maybe the city could set up a pig food stand where the public could buy porcine treats to feed them, much like tossing herring chunks to the seals at Point Defiance Zoo. Why, locals could even bring their kitchen garbage from home and heave it over the fence.

What could be a more family-friendly activity than feeding pigs? (An obvious joke here was withheld at the request of people who know better than I the boundaries of acceptable decorum.) And what could be more environmentally friendly than recycling your table scraps? Nothing.

As if all those community benefits aren’t reason enough, a simple name change to The Pig Village at Harbor Hill would turn the place into a regional tourist destination. A cute name like that, conjuring visions of adorable little piglets going about their daily lives, would draw visitors from all over Puget Sound. With any luck, they’d bring their own kitchen garbage with them.

Of course, there could be no slaughtering done at The Pig Village at Harbor Hill. That would risk taking the edge off the family fun vibe. For butchering, they’d have to be taken someplace else. Like Purdy.

New business

At the end of our previous column we went back to the woods to find another question of local history on logging. It concerned a story that was reported in newspapers across North America and even in Australia.

In 1907 while yarding timber for the Day Logging Company in Rosedale, steam donkey engineer Elmer E. Marble saw and seized an opportunity to hunt something not normally encountered by loggers. Instead of a rifle, he used some of the company’s logging equipment.

What did E. E. Marble hunt in Rosedale while logging?

Answer: The first hint we gave was that it wasn’t a rogue elephant. That could’ve been interpreted as meaning it was a circus elephant, but it wasn’t. It was a shark. A BIG shark. Billy Sehmel knew that, and posted the correct answer on the Gig Harbor Now Facebook page within an hour of the question being posted there.

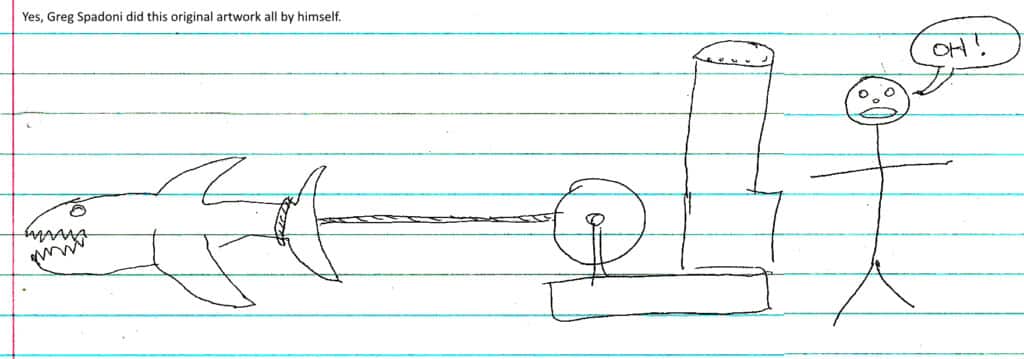

It’s tempting to claim the question was too easy, but it wasn’t. The explanation for the quick answer is simply that Billy Sehmel knows local history. His correct answers do take the surprise out of reading this week’s column, but only partially. Even he doesn’t know how we’re illustrating this week’s story. It’s not easy coming up with pictures of an obscure event in 1907, but we managed. And the results are the highlights of this week’s column.

What logging equipment did he use in the course of his hunt?

Answer: While the most logical answer might seem to be an axe or a peavey, Billy Sehmel also knew that E. E. Marble actually used the Day Logging Co.’s yarding equipment.

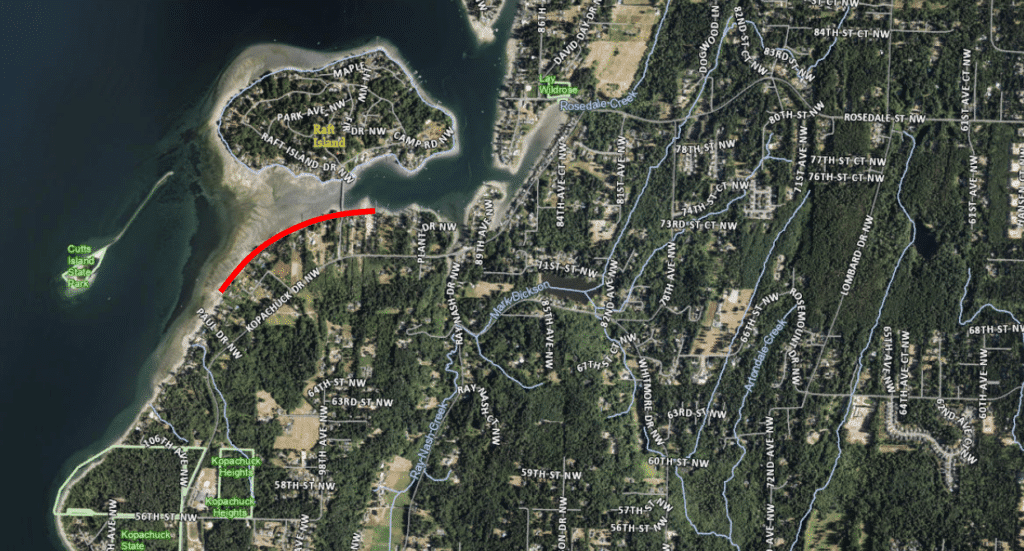

In what was perhaps the only case of its kind on the entire Gig Harbor and Key peninsulas, while logging in Rosedale, Mr. Marble spotted a shark stranded on the beach near Raft Island, and went after it with the logging equipment he was using. It was the biggest shark he or anyone he knew had ever seen in Henderson Bay.

According to The Seattle Post Intelligencer, the shark, discovered by the logger on Saturday, October 19, was “supposed to be of the man-eating variety … twenty feet long, as thick through as the body of a horse, and is estimated to weigh from 1,400 to 1,500 pounds.” It was stranded on the beach when the tide went out.

From the way its ribs are showing, this Basketball Barbie-eating shark doesn’t look as if it weighs from 1,400 to 1,500 pounds, like the one described in the 1907 newspaper article. It probably weighs closer to an ounce and a half. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Why Mr. Marble did so was not disclosed, but he took a logging team of horses out onto the mud, managed to get a rope around the shark’s tail, and tried to yard it further up the beach to the high tide line. The stranded animal was entirely too big for the team to budge, however, so that method was abandoned.

Marble then fastened enough pieces of rope and cable together to reach the drum line of the steam donkey yarder he was using in the woods near the shore, and easily pulled the shark across the mud.

“Flapping and vigorously struggling, the big fish was hauled high and dry, and as the life in the monster seemed strong, the rope around its tail was tied to a tree to prevent its possibly struggling back into the water when the tide reached its height.”

Being totally stumped on how to illustrate the dramatic action of this week’s story, I decided to employ my considerable drawing skills and do the artwork myself. In this detailed and life-like sketch, E. E. Marble yards the struggling shark to higher ground.

Pointless cruelty

The act of tying the beast to a tree so that it would die instead of swimming free when the tide returned was pointless and cruel, which the logger recognized only after the shark died the following day. “Marble and some of his friends, on discovering its great vitality, regretted that they had not tried to keep it alive,” the Post Intelligencer wrote. “Mr. Marble will collect the teeth and keep them as curiosities.”

E. E. Marble of the Day Logging Company yarded himself a shark near Raft Island in Rosedale in 1907. From the brief description of the beach in the newspaper article, the most likely spot is indicated by the red line. This photograph, having been taken at low tide, clearly shows the exposed mud flats near the island. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

In addition to preventing the shark from escaping on an incoming tide, yarding it to the edge of the beach where even a high tide couldn’t refloat it and carry it away also ensured that an overpowering stink of rotting fish would engulf the immediate area for a long time to come.

Had there been such a competition at the time, Elmer E. Marble would’ve been the odds-on favorite to win Putz of the Day.

Perhaps a comparison to Elmer Fudd isn’t inappropriate after all.

New question

While he may not have realized it at the time, there’s a consequence to Billy Sehmel knowing the answer to both of our previous questions: he’s now on the spot to answer this week’s question!

It’s no more difficult than the last two, and look at how he aced those.

Shark yarding is a tough subject to top, but not the story of a rotting shark corpse. Just about anything added to this week’s column will compare favorably to that. Even this:

It’s standard practice to celebrate winners, and even runners-up. But the passage of time tends to leave the runners-up behind. We’re going to take a new look at a couple of forgotten second and third-place winners. If not for the first-place entry, one of them would’ve taken the top prize. How would that have affected the lives of people today?

The Key Peninsula is defined as that part of Pierce County lying between Henderson Bay and North Bay. It had no specific name before 1931. Early that year a group of businessmen on the not-yet-named peninsula ran a contest to give that land mass a title. With an increasing population, it needed its own identity.

The contest judges included Dr. Roy Gilbert, Edgar Laden, Albert Sorenson, Chet Hipp, Alden Visell, and Joe Wolniewicz.

It was not a foregone conclusion that the winning name would precede the word “peninsula,” though the top two entries were intended to do that. The third-place winner was a standalone word.

First place, as should be obvious, was “Key,” submitted by 66-year-old Edward M. Stone of Lakebay. He won $25 for that suggestion. But what about the runners-up? If Mr. Stone hadn’t come up with “Key,” the peninsula would have a different name today. What names did the second and third place winners submit? And who were they?

A point well proven

See? Those two questions are much, much better than the smell of rotting fish. And by rolling them both into a single sentence, they become the question of the week:

In 1931, what were the two runner-up entries in the contest to name what is now the Key Peninsula, and who submitted them?

We’ll have the answer on July 1. We’ll follow that up with a tale of what a group of bored local teenagers did on a long-ago 4th of July evening. If your kids or grandkids are easily bored today, imagine how hopeless they’d have felt in the days before social media. They might’ve actually been driven by desperation to … step outside!