Community Education

Peninsula School District data shows post-pandemic spike in bullying

Peninsula School District saw a spike in behavior classified as “harassment, intimidation and bullying” following the pandemic, according to data shared Tuesday with the school board.

Education Sponsor

Education stories are made possible in part by Tacoma Community College, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

The report comes amid ongoing complaints from the public in recent months of a culture where bullying and discriminatory harassment go unchecked in Peninsula schools.

Top district officials have acknowledged the complaints and committed to addressing the issue.

“This is our work. We have to set the tone in our schools. Our administrators are very serious about behavior,” Superintendent Krestin Bahr said during the March 5 board meeting.

Bahr, who has three grown children, encouraged parents to partner with the district in helping manage the often-erratic emotional highs and lows of the developmental years.

“Raising children is difficult,” she said. “And being a child is difficult, especially in this world.”

Board digs deeper on behavior

Following a preliminary report March 5 on how the district deals with misbehavior, the board took a deeper dive on Tuesday. Board members heard from a panel of principals, counselors and community partners about strategies to manage harassment, intimidation, bullying and discrimination.

At Tuesday’s meeting, the community group Gig Harbor for Racial Justice submitted a letter to the board calling for the district to take definitive action against racism, homophobia and other forms of discrimination. The group was joined by members of Gig Harbor Moms for Peace and Pride Gig Harbor.

“For far too long, these incidents have persisted, causing harm and perpetuating a climate of fear and inequity in our schools,” the letter read.

As in meetings over the past couple of months, the board also heard from several people with complaints about the district’s handling of behavior issues. Many of those people told the board they were left feeling like their kids didn’t belong.

Spike in bullying

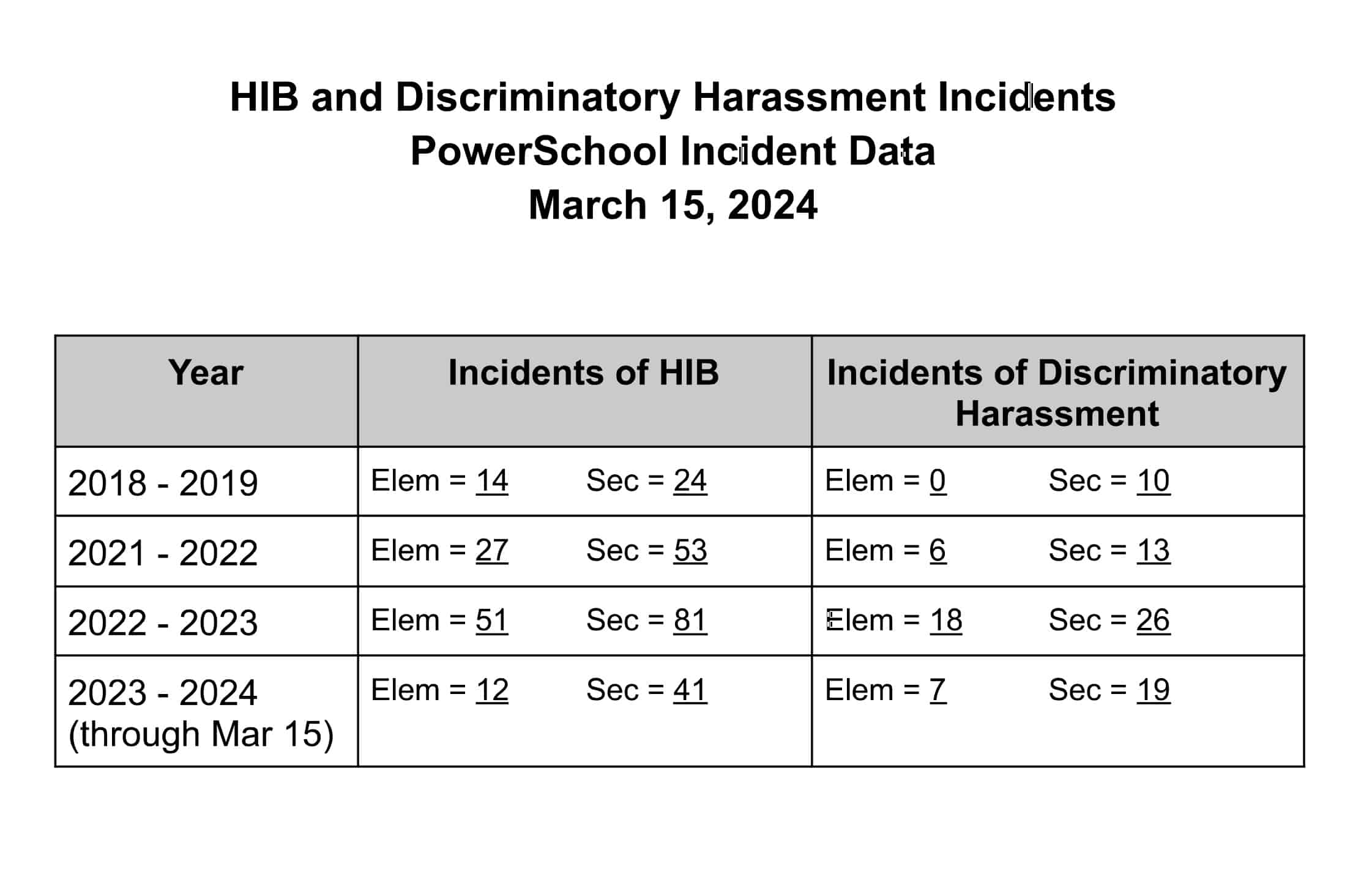

Assistant Superintendent Dan Gregory presented data on behavior since the 2018-19 school year. Data was not collected during the pandemic, in 2019-20 and 2020-21, when students were attending school remotely. The data show a spike in incidents of harassment, intimidation and bullying at both the elementary and secondary levels in 2021-22, when students returned to school.

In 2018-19, there were 14 HIB incidents reported across all 10 elementary schools. That number nearly doubled in 2021-22 to 27, and nearly doubled again in 2022-23 to 51. This year to date, there have been just 12 incidents, suggesting a downward trend.

At the secondary level, the number of HIB incidents more than tripled between 2018-19 and 2022-23. In 2018-19 there were 24 HIB incidents; 53 in 2021-22 and 81 in 2022-23. The district has two comprehensive high schools, an alternative high school and four middle schools.

Data so far in the 2023-24 school year show 41 incidents across all secondary schools. Gregory noted that if incidents were to continue at that pace, the number by the end of the school year would be 62.

Data on discrimination

Incidents of discriminatory harassment — in which victims are targeted based on race, gender, sexual identity and disability — inched up at the elementary level from none in 2018-19 to six in 2021-22, then jumped to 18 in 2022-23. This school year, there have been seven incidents to date.

At the secondary level, incidents of discrimination increased from 10 in 2018-19 to 13 in 2021-22 and 26 in 2022-23. There have been 19 incidents so far this school year. Were that pace to continue through June, the number of incidents would hit a four-year high of 29.

“We are seeing some increases at the secondary level,” Gregory said. “We’re looking for it. We’re paying attention to it (and)… addressing it.”

Group’s call to action

Gig Harbor for Racial Justice was formed in 2021. The group is made up of people seeking to educate themselves and others about issues related to racial equity and discrimination, according to co-founder Joy Stanford. But the group’s focus goes beyond race to include members of the LGBTQ community, neurodivergent individuals and people with disabilities.

Joy Stanford reads a letter from Gig Harbor for Racial Justice to the Peninsula School Board on Tuesday, March 19.

The group’s letter came from a coalition of people representing other advocacy groups (Gig Harbor Moms for Peace and Pride Gig Harbor) as well as concerned parents and other community members.

The letter calls on the district to “acknowledge the existence and severity of the acts and words of discrimination, anti-queer hate, bullying and racism” within the district. They want the district to adopt a restorative justice model of discipline (something district officials say is already in practice).

The group wants the district to do a better job of training staff in recognizing discrimination and intervening. And they call on the district to hire a more diverse staff.

“We will work collaboratively with the PSD board and district leadership to advance these critical goals to ensure our district becomes a safe and inclusive environment for all students,” the letter says. “We ask that the district work with us as well.”

Study session take-aways

Panelists reported to the board multiple ways in which they try to proactively address behavior before it gets out of hand. Within sessions on “social and emotional learning,” students learn about the continuum of misbehavior, from conflict they can learn to solve on their own to incidents that require adult help.

Regardless of whether behavior rises to the level of HIB, school staff stand committed to act swiftly to protect victims and deter future assaults, panelists said. Discipline aims to help aggressors learn from their mistakes. Restorative justice is used whenever possible.

Panelists addressed the likely impact of pandemic isolation on students’ social skills and behavior. Several officials suggested that strategies implemented after the pandemic are bearing fruit, as evidenced by the drop in incidents at the elementary level.

Investing in relationships

Building relationships was a common theme among panelists at both the elementary and secondary level.

Staff at Discovery Elementary invest a lot of time nurturing relationships with students so that they will feel comfortable coming to them with problems or making a report of aggressive behavior, said panelist Alex MacAulay, site coordinator for Communities in Schools Peninsula, an organization with staff embedded in schools to give extra support to students and staff.

Counselors and principals track behavior data and evaluate each student’s social and emotional wellness to make sure kids don’t fall through the cracks, especially those who may be reluctant to report an incident.

When students don’t report

If staff are making a good-faith effort to snuff out bullying before it happens, some kids aren’t feeling it.

Bethany Davis, mother of six, said her kids have been teased and bullied for myriad things, from clothing and hairstyles to sexual orientation. Use of the N-word is rampant. So are homophobic slurs, her older kids tell her. When a student on the bus cut her daughter’s hair with scissors, her daughter was reluctant to report it because she believed “it wouldn’t do any good.”

“Our kids do not trust their teachers or administrators to have their backs,” Davis said. “I know there are adults who care. Every adult in this room cares. That’s why we’re here, but that point is moot if the kids don’t believe it.”

‘We have work to do’

Mike Benoit, principal of Peninsula High School, talked about the ways he and his staff work to create a safe, welcoming atmosphere. He said the “student voice” is active at PHS, and students help create a positive culture within the school. There is a newly formed Diversity, Equity and Inclusion group of students at PHS as well as a new People of Color Club.

“I think there’s a lot of things going well at our schools,” Benoit said. “But when I hear some of our parents, it’s clear we have work to do.”

Gregory, too, acknowledged community comments and the apparent disconnect between the hard work of staff, especially school counselors, and public perceptions.

“Our kids have to know we care, and they have to believe we care,” Gregory said. “And so, we’re listening and we’ve got great people who care a great deal, and we just need to keep working on those things.”