Arts & Entertainment Community

The magnificent Ukrainian pysanka … so much more than an Easter egg

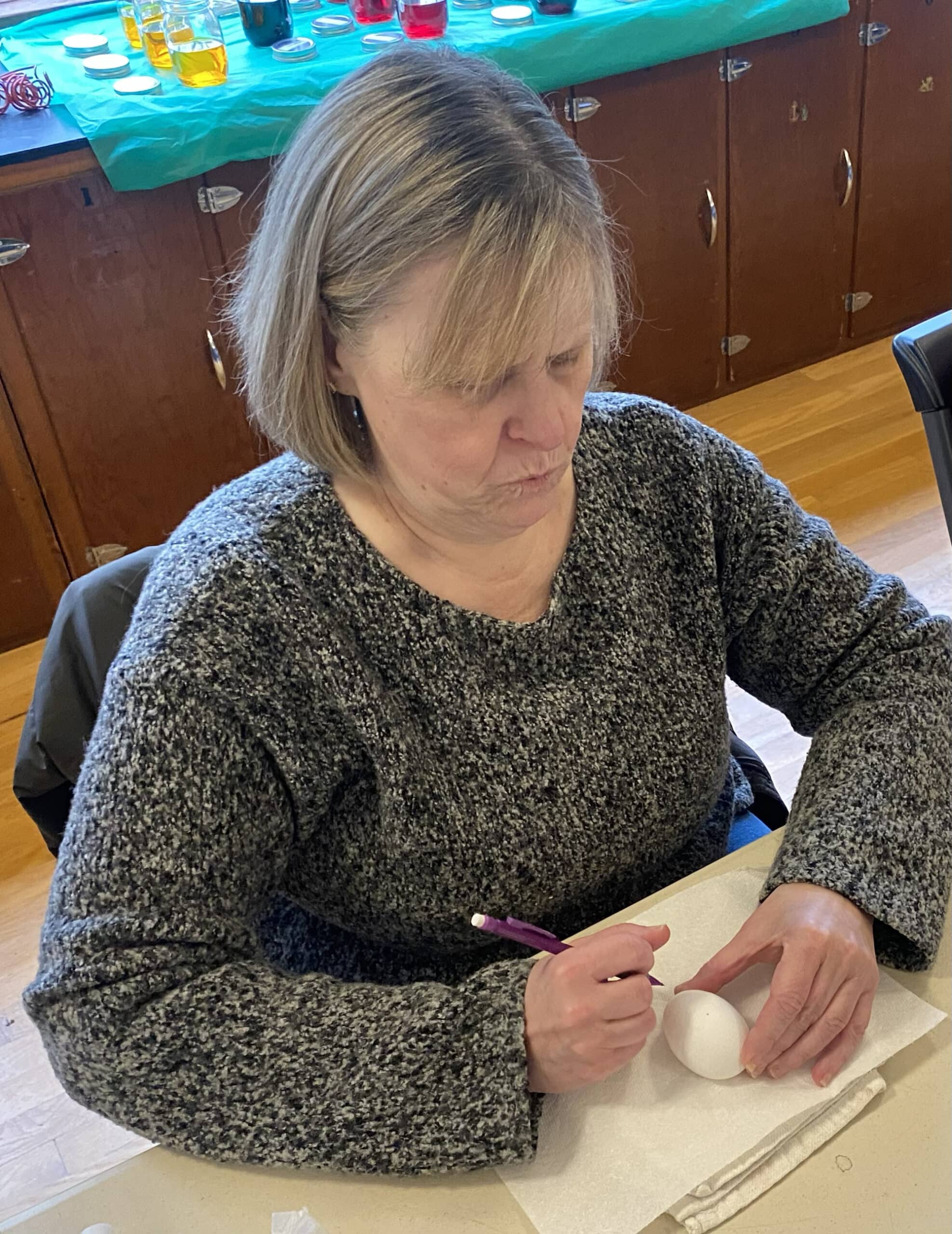

Mary Whittington pursed her lips in fierce concentration March 2 at the Nichols Community Center on Fox Island. Before her lay the task of drawing intricate lines on a (raw) egg, overlaying them with beeswax and dipping the egg in successive jars of dye to produce her first pysanka.

Arts & Entertainment Sponsor

Arts & Entertainment stories are made possible in part by the Gig Harbor Film Festival, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

It’s an Easter egg and so much more.

Mary Whittington draws a design on a raw egg, the first step in creating a pysanka, during a class March 2 at the Nichols Community Center on Fox Island. Photo by Christina T. Henry

The Ukrainian folk-art tradition of pysanka dates back to before the birth of Christ, when people decorated eggs believing in the great power embodied in them. Eggs symbolize the release of earth from the icy grip of winter and the coming of spring. With the advent of Christianity, the eggs came to symbolize the Resurrection and promise of eternal life.

The Ukrainian people passed down the art of pysanka through generations, according to the Ukrainian Gift Shop, a family-owned business in Minnesota which instructor Kathy Bell of Gig Harbor highlights as a source for materials in her classes.

Making the elaborately decorated eggs (“pysanky” in the plural) is not as complicated as it sounds, Bell insists. “If you can draw a line, you do can do a pysanka,” she said.

Easy for her to say. Bell has been at it for decades.

Classes fill up fast

Formerly from California and not of Ukrainian descent, Bell learned about pysanka when her mother, an artist, was unable to attend a class she’d signed up for. Bell, then 18, took the class in her place. She taught her mom, Judy St. Hill Schiner, and the two started making and displaying eggs at her mother’s studio. That led to teaching classes, which continued after the family moved to Gig Harbor in 1989.

“I can’t even tell you how many students we’ve had over the years, hundreds,” Bell said.

Instructor Kathy Bell of Gig Harbor displays pysanky, Ukrainian Easter eggs, during a class March 2 at the Nichols Community Center on Fox Island. Bell has been teaching the art of pysanka in the Gig Harbor area for more than 30 years. Photo by Christina T. Henry

Her four-hour class on March 2 will be followed by a second one on Saturday, March 9. Classes fill up quickly but spaces remained available as of Wednesday for the March 9 class, said Candy Wawro, the Fox Island Community & Recreation Association coordinator.

The upcoming class runs noon to 4 p.m. at the Nichols Community Center. The cost, $50, is payable at the door. For more information, visit the Fox Island Community & Recreation Association website.

Symbols of hope old and new

Ukrainians believe the pysanka (from the Ukrainian word “pysaty” or “to write”) possess enormous power, according to the nonprofit Ukrainian Institute of America in New York City.

People originally gave pysanky the way we give greeting cards: for new babies, new homes, as a wish for prosperity or even to mark a death, said Bell. Their decorations feature symbols old and new.

Pine needles represent health, stamina or eternal youth, according to a flier Bell gave to class participants. Birds signify fulfillment of wishes and fertility. Poppies, beloved of the Ukrainian people, symbolize joy and beauty. There are several varieties of crosses, representing Christ or the four corners of the world. The saw, also known as “wolves’ teeth,” represents fire, life-giving heat, loyalty and wisdom.

Colors, too, are symbolic. Lighter colors like yellow and white symbolize innocence and purity. Red and orange represent the sun; blue, the sky with its life-giving air; and green, new growth, spring and hope. Dark colors represent eternity and darkness before the dawn.

“Legend has it that as long as pysanky are decorated, goodness will prevail over evil throughout the world,” according to a history of pysanky on the Ukrainian Gift Shop’s website quoted on Bell’s flier.

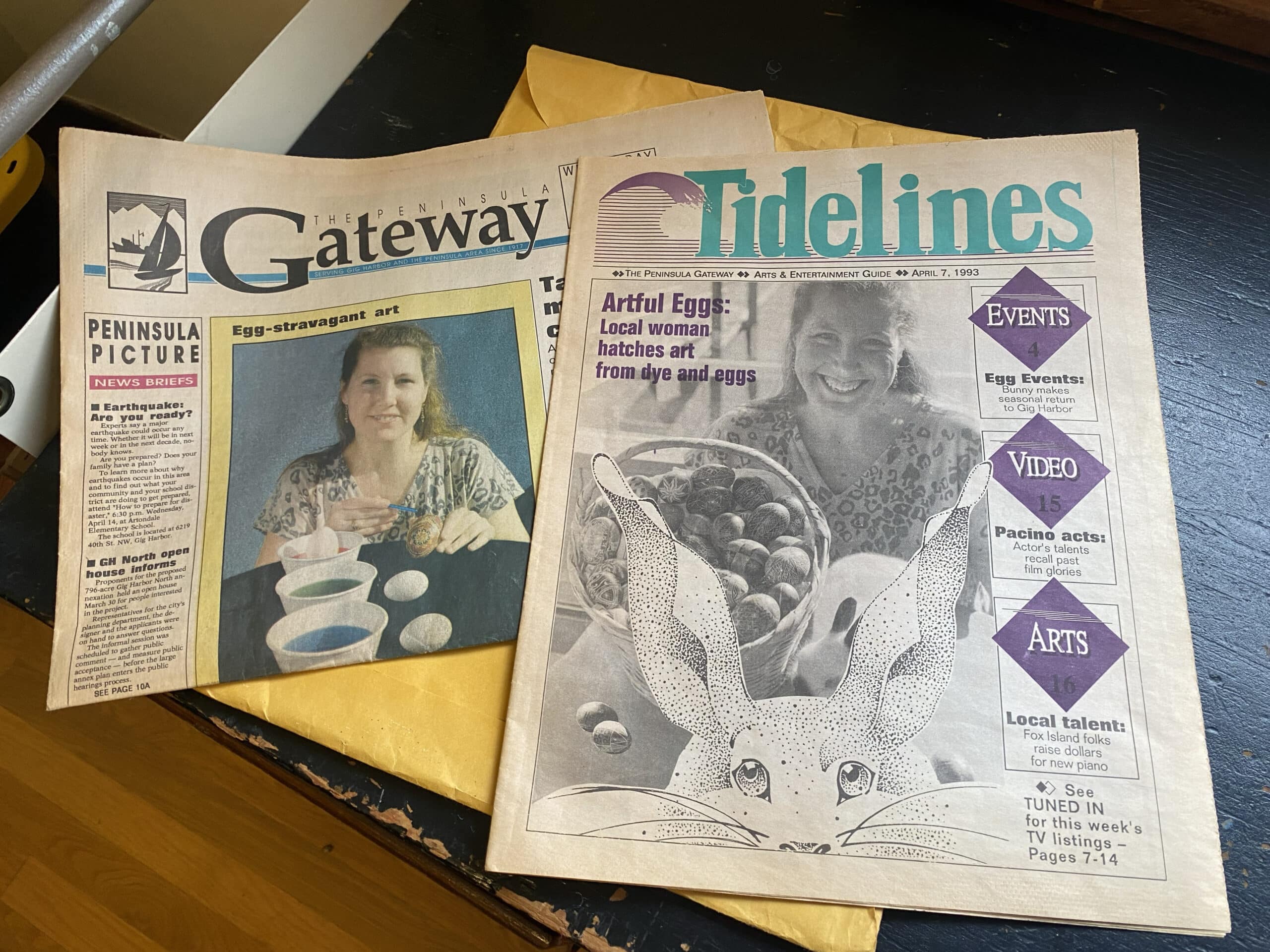

Kathy Bell has been teaching the art of pysanka in the Gig Harbor area for more than 30 years.

The power of pysanky

Elko Perchyshyn, whose mother and grandmother founded the Ukrainian Gift Shop in 1947 and who is now its manager, affirmed the widespread belief in the uplifting power of the eggs. “It’s a long-held fact,” he said.

In a documentary filmed in 1976, Perchyshyn’s mother Luba Perchyshyn explains the history of pysanky from pagan times, when the return of the sun in spring would have held tremendous significance to the ancient Ukrainian people.

The star or rosette, featured on the egg design in Bell’s class, was a favorite design with endless variations, Perchyshyn’s late mother says in the film. “To ensure the yearly return of the god, his image was captured on the egg in springtime.”

Animals, birds, trees and plants on the eggs celebrate new life and prosperity.

“To a people whose lives were tied to fields and forests, springtime promised an abundance of riches,” she says. “As Christianity spread across Ukraine, the old meanings changed.”

Grapes, that symbolized the harvest, came to mean the growing church. The triangle, symbolizing birth, life and death, came to represent the Holy Trinity.

So, too, did old methods give way to some new materials and techniques, but the basic process of pysanka remains as it has been for millennia.

Pysanky, Ukrainian Easter eggs, during a class March 2 at the Nichols Community Center on Fox Island. Photo by Christina T. Henry

Let’s do this

The art of pysanka uses a technique called wax and dye resist, similar to batik. Wax is applied in lines to create a design, and the egg is dyed. More wax is applied, and a darker dye is applied, again and again, all of it working backwards toward an intricate (usually) geometric design adorned with symbols, animals, flowers and birds.

Bell advises students to use fresh eggs, which have a harder shell. The eggs can be duck or goose eggs, but mostly chicken eggs are used. They can be any color, from white to dark brown. In fact, the variety of colors creates interesting effects with the dyes.

Raw eggs and finished pysanky during a class March 2 at the Nichols Community Center on Fox Island. Students followed the design of the pysanka egg at the top right. Photo by Christina T. Henry

Step 1

Bell showed students how to draw lines on the egg with a mechanical pencil, then trace the lines with beeswax using a special tool called a “kistka.” The kistka has a small funnel for melted wax and a hollow tube through which the wax flows. The students had to keep heating the wax over a candle to keep it flowing. It’s fiddly work requiring a steady hand, but Bell’s students all managed admirably.

Step 2

The eggs were dipped in a jar of yellow dye. The areas covered by wax would remain the color of the shell.

Step 3

More lines were added, and a star pattern emerged with leaves and sheaves of wheat. After new patterns were added, the eggs were successively dipped in orange, red, green and later dark blue or black as the background color.

A tool called a “kistka” applies wax to eggs. The kistka has a small funnel for melted wax and a hollow tube through which the wax flows onto the egg. Photo by Christina T. Henry

“I’ve always been curious how to do it. They’re so pretty,” said Lauren Atwill, waiting her turn at the dye table.

Atwill will is not a crafty person. “Not at all,” she said. “But I can draw lines.”

Step 4

Wax is not applied to the final color. When the egg has dried, the beeswax is removed by holding it up to a candle and wiping away the wax a little at a time. As if by magic, the beautiful design appears.

Step 5

The eggs are varnished to make them stronger and glossier. In olden times, people used animal fat to seal the eggs, according to the film.

Step 6

The eggs are blown to remove the insides. Some artisans roll the raw eggs in a painstaking process, turning them over little by little over a matter of weeks. Rolling the eggs causes the yolk and white to mix and solidify, Bell explained, but missteps can cause gases to build up, and the egg will burst.

In fact, said Bell, there are many ways to go wrong with pysanka. About 25 percent of eggs are lost during the process. But no problem, she said. Just pick up another egg and start again.

Jars of dye await eggs during a class March 2 at the Nichols Community Center on Fox Island. The art of pysanka uses a wax and dye resist method, similar to batik. Artists apply wax to the shell of the egg in designs that are not taken up by the dye. They make the design in stages, each with a new color of dye. Finally, they varnish the egg and remove the with heat from a candle to reveal the design.

Living installation signifies hope

The Ukrainian Institute of America is hosting an installation of pysanky donated by people from around the world to show solidarity with the people of Ukraine as the Russian invasion of that country enters its third year.

According to the institute, an ancient Ukrainian legend tells of an evil monster chained to a mountain cliff. Each year, the monster sent henchmen to count the Pysanky. If the number was high, the henchmen would return and tighten the monster’s chains. If the tradition waned, the chains loosened, leaving the monster free to wander the earth causing destruction.

“This institution encourages people of all backgrounds, beliefs and ages, including children, to enrich a living installation of pysanky by contributing their own egg, hand decorated with traditional Ukrainian techniques and motifs,” the institute says. “As pysanky continue to arrive and their numbers increase, so will the symbolic power of the installation grow.”

Pysanky donated to “The Pysanka: A Symbol of Hope” are sent to Ukraine and used, as historically, in rituals of renewal such as being put in beehives, buried in the ground and placed on the graves of children killed in the war.

Pysanka instructor Kathy Bell shows Lauren Atwill how to immerse her egg in dye during a class March 2 at the Nichols Community Center on Fox Island. Photo by Christina T. Henry