Community Education

Growing chorus of voices decries racism, bullying in Peninsula schools

Over the past month, the Peninsula School Board has heard a stream of complaints about racism and bullying. The speakers and incidents they describe appear to be unrelated except for the theme: Discrimination against students who are different.

Education Sponsor

Education stories are made possible in part by Tacoma Community College, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

On Jan. 30, a representative of Gig Harbor High School’s Black Student Union reported ongoing racial slurs used against students of color. On Feb. 13, two parents spoke passionately about bullying their children have incurred, one directly related to sexual orientation. And a former district employee described fellow staff members belittling students of color and those who are immigrants.

At the school board meeting on Tuesday, Feb. 27, more voices joined the growing chorus.

Parent calls bullying a ‘systemic problem’

Dr. Hugh Pratt, the parent of two students at Goodman Middle School, on Tuesday said his children recently suffered “physical, verbal and cyber-mediated episodes of bullying” from a student at the school. While Pratt commended the response of Vice Principal Dawn Musgrove, he noted a recent report on KIRO TV about a student at Kopachuck Middle School who in December was assaulted by another student on a school bus. The attack was recorded on video.

Pratt said that what he thought was an isolated incident affecting his kids he now sees as a “systemic problem” in the district negatively affecting not only victims but abusers.

“This is not something we can compromise on,” he said. “The harm to the children is real. It’s long-term. It affects people into adulthood.”

The outcry comes against the backdrop of a School Safety Plan report presented to the board on Feb. 13 in which Harassment, Intimidation and Bullying were discussed at length. Assistant Superintendent Dan Gregory said the district is considering upgrades to its reporting system. He added the district would rather see “over-reporting” of possible HIB incidents than under-reporting.

“We don’t want to put a chill on reporting. We want to ease reporting,” he said.

Racial slurs pervasive

James McCourt, a junior at Gig Harbor High, addressed the board on Jan. 30 on behalf of the Black Student Union, which was formed a year ago and welcomes all students. The group celebrates Black culture and heritage, and also seeks to fight racial discrimination, leaders said last year.

McCourt described what it’s like to be one of a minority representing less than 1 percent (0.7%) of the district’s enrollment.

“For Black students, this leads us to feel underrepresented and like we don’t fit in,” he said. “But as well as feeling different, people treat us different, whether it’s being called slurs or saying offensive jokes or comments to our faces or behind our backs.”

Leila Jeneby, a co-founder of the BSU, said last year she was taken aback after moving to Gig Harbor by the frequent use of the N-word around school. In January 2023, the district investigated allegations of a racial slur at a girls’ basketball game. An independent investigator was “unable to substantiate” the claim.

McCourt suggested the board approve “age-appropriate” teaching about racism, either as part of the curriculum or through guest speakers. “We feel the actions of people can be changed with education,” he said.

Leila Jeneby (in blue) and others started a Black Student Union at Gig Harbor High School in January 2023. With her in this picture are fellow club members Jasmine Lopez and Anna Bartlett.

Other races, groups targeted

“Peninsula School District has a racism issue, and for those who do not think we do, it is a case of denial,” speaker Chris Dougherty, told the board on Feb. 13. “As a woman of color who presents as white and has an Irish married name, I have been privy to conversations when I worked for the school district, conversations about disdain for students of color, students who immigrated to the U.S. and students who are learning English as their second language.”

Dougherty said she’s heard from Black students at the middle and high school level about “the use of the most hateful racial slurs toward students of color.”

The mother of the student in the KIRO report said her son was told, “something about, ‘It must suck to be Asian.’”

Dougherty returned on Tuesday with a list of recommendations to the board, most but not all related to equity and inclusion. Among them, she asked that the district “combat and address racial and homophobic slurs in our schools through education on diversity and cultural understanding, while also backing administrators in disciplining repeat offenders.”

Also on Tuesday, the president of the Peninsula Education Association, Carol Rivera, acknowledged other speakers “and their concern for the safety and well-being of their children.” Rivera said her union has created a leadership committee focused on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. The group includes members who are working in schools.

“So that group gathered today with the focus to look at the ways that we can engage student voice and not just hear it but also find ways for them to lead and be involved in that,” she said.

LGBTQ kids in pain

The father of a fifth-grade student became emotional at the Feb. 13 meeting speaking about bullying his daughter endured at her former elementary school. He said she was punched in the face by her alleged aggressor.

The father blames the same student for rumors about his daughter getting killed after she made a comment to a group of students about kissing a girl (not during school). He said the incident was poorly handled by school staff, making his daughter lose confidence in herself and trust in the adults in charge. He is appealing a denial of his HIB compliant to the school board.

At the same meeting, parent Aria Messer, whose family is of mixed heritage, said she supports more diversity in education. Messer has three children, two in Peninsula schools.

“And of my three children, two are queer,” she said. “I hope no one has the horror of watching their child curl up in a ball unable to breathe, eyes wild around the room and saying they don’t want to be alive anymore because every day that they go to school they are harassed and bullied for who they are.”

Messer spoke again Tuesday, noting others who have called out bullying.

“It’s clear based on the testimony of so many that harassment, intimidation and bullying is an epidemic in our district,” she said. “It seems to be a prevalent part of school culture that I’m afraid is becoming a norm.”

Messer advocates the use of restorative justice in which counselors or others mediate discussion between the victim and the aggressor. “The process is centered around respect, dignity and mutual concern by creating a space for repairing harm that’s done,” she said.

District addresses safety audit

The district’s management of Harassment, Intimidation and Bullying is part of its overall School Safety Plan, a wide umbrella that includes areas such as building security, emergency communications, event safety, bus safety and more. The report to the school board on Feb. 13 was a mid-year update on steps to address a 2021 safety audit of the district.

The preamble of Peninsula School District’s policy on harassment, intimidation and bullying.

Gregory went over how the district handles HIB complaints, a response that follows state and federal requirements.

HIB is defined as behavior that: physically harms a student or their property; substantially interferes with a student’s education; is so severe, persistent or pervasive that it creates an intimidating or threatening environment; or which substantially disrupts the orderly operation of school.

The policy highlights harassment, intimidation or bullying that is motivated by the victim’s race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability, among nearly a dozen specially protected groups.

Staff and students at all grade levels receive training in responding to bullying, including how to advocate for yourself and how to (safely) intervene, Gregory said. “We kind of hammer that home. Don’t stand by.”

How the district handles HIB

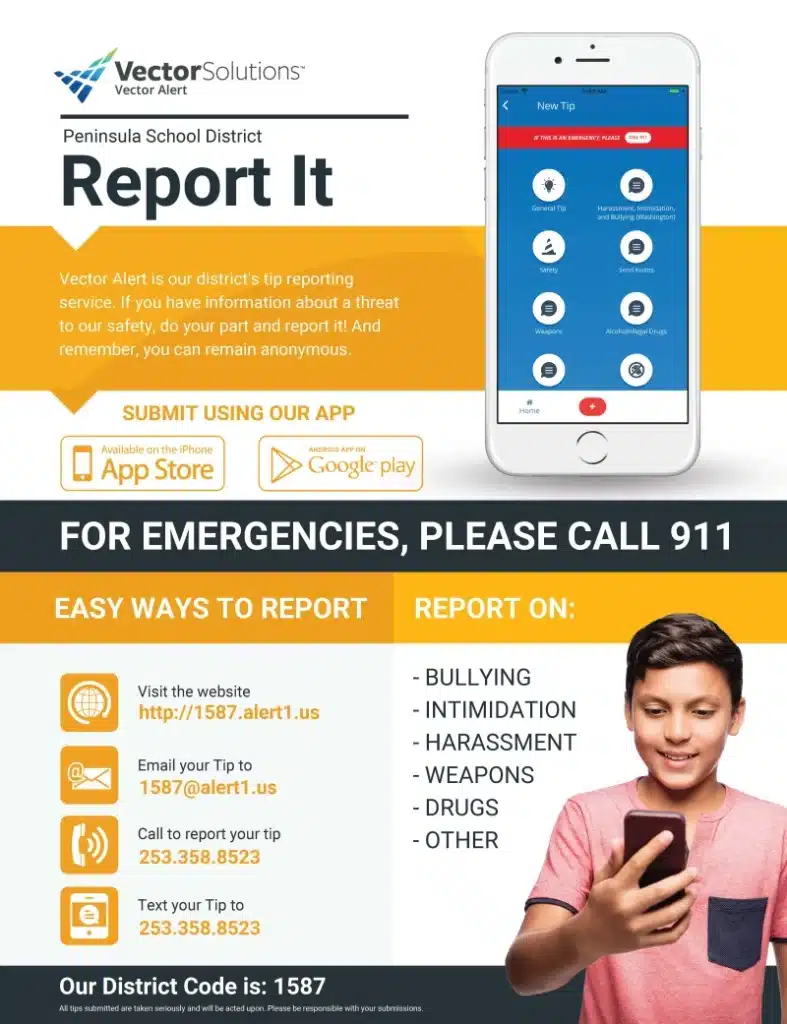

Staff are taught three steps in response to a possible incidence of HIB: intervene, support the victim and report the behavior. Staff use an internal reporting form and HIB checklist. Students, parents and community members can report via the district’s Vector Alert Tip Reporting system. Gregory said the district is looking at upgrades to its reporting system, such as access by QR codes, to make it easier for the public to use.

Peninsula School District uses a system called Vector Alert to allow people to report bullying, harassment, intimidation and other safety threats.

Once a report of suspected HIB is made, district staff will interview witnesses to corroborate claims. If the behavior meets the definition of HIB, the district will take “corrective action,” Gregory said.

Discipline could be anything from a no-contact order with the victim (separate seating in classes or on the bus, for example), to emergency (short-term) expulsion or “exclusionary” (long-term) expulsion and, if warranted, contacting law enforcement. The statewide trend is to avoid expulsion whenever possible and use other means of discipline, Gregory said.

The district’s school security officers and other security staff work with school counselors on “threat assessment,” to proactively respond if a student is deemed to be a threat to him or herself or to others.

Student privacy rules

During a HIB investigation, the district is supposed to notify parents of both the alleged aggressor and victim along the way. Gregory said parents of the victim are often frustrated because they are unaware of any consequences.

Student privacy laws, however, forbid public disclosure of student discipline. A victim’s parents can be made aware of components of a safety plan like a seating arrangement, but not of discipline like in-school suspension or expulsion.

“That’s a difficult thing, and we know that that’s a difficult thing for parents to understand,” Gregory said.

The district sometimes uses “restorative justice” if both the victim and aggressor are willing, he said.

District responds on bus incident

The mother of the Kopachuck bus assault victim told KIRO she didn’t think the district had ruled the incident a case of HIB. That may be because of how the district phases its form letter to parents.

According to KIRO: “’The investigation has found that Ethan was more likely than not physically bullied,’ she (the mom) read from the report the school sent on the incident.” (Emphasis added by GHN)

The mom indicated she thought that meant the behavior was not deemed bullying. In fact, according to a statement by the district sent to KIRO and other media, the aggressor’s behavior did meet the definition of Harassment, Intimidation and Bullying. The district took corrective actions “including disciplinary action and support for the targeted student.” The district’s statement also reiterated student privacy rules.

“It’s disappointing when we become aware of behaviors such as these, and we feel for students who are targeted,” Gregory said. “Feedback we have received from recent situations indicates the phrase in the HIB parent letters ‘more likely than not,’ which was intended to affirm a finding of HIB, is not always clear. We will be reviewing and revising this language to provide greater clarity.”

Parents’ rights to appeal

If a victim’s parent disagrees with the initial HIB investigation, usually by a school’s principal or other top administrator, they can appeal to the district superintendent or their designee. If they still are dissatisfied, they can appeal the complaint to the school board. The board makes no new findings, however. They simply audit the process to make sure steps were followed correctly.

Gregory encouraged students and parents to report behaviors even if they may not rise to the level of HIB.

“Even if the report is believed not to be HIB, we still want to record it on our HIB forms,” Gregory said. “Regardless of whether it’s HIB or not, we still apply corrective measures and still offer a support plan (to the victim).”

Gregory said he appreciated speakers’ comments about bullying. “We are always looking to improve,” he said.