Business Community

Gig Harbor Boat Works: The biggest little boat builder in town

In a city that prides itself in its maritime past, the names of its boat builders are legend.

Skansie, Crawford, Anderson, Glein, Hoppen, Maloney, Robertson … Huh? Robertson?

Yeah. Robertson. You don’t recall seeing that name on a waterfront boatyard? Don’t bother looking. It’s not there, although you probably have driven by a simple sign on Peacock Hill Avenue: Gig Harbor Boat Works.

That sign, blocks away from any navigable waterway, marks a long downhill driveway past a family home to a neat, one-story, two-room, red building perched beside an acre or two of meadow-like lawn.

The sign for Gig Harbor Boat Works on Peacock Hill Avenue.

Dinghy titans

Over the last 38 years, from that cramped and unimposing 1,200-square-foot structure, David Robertson, his family and crew have delivered between 2,000 and 3,000 boats. They made so many that no one in the firm acknowledges having counted them all.

One thing is certain: Gig Harbor Boat Works has built more vessels than all those other boatyard folks, lumped together, built in their lifetimes.

Granted, these vessels were not the grand ferries, iconic fishing boats, yachts or sailing sloops you might associate with those earlier names.

They were — and are — mostly dinghies.

Interesting word, dinghy. It likely comes from from Hindu “dingi,” a small rowboat used on the rivers of India.

A Gig Harbor Boat Works display at the Seattle Boat Show in February. Photo by Chapin Day

A hobby becomes a vocation

A short, light, fiberglass rowboat. That’s David Robertson had in mind when he built his first one for his family in the 1970s. They needed a boat light and slippery enough to tow easily behind his family’s cruising sailboat — yet sturdy enough to survive years of beachings on the Northwest’s rocky shores.

Boating friends prompted Robertson to build similar ones for them, too. Given that — not to mention an inventive and entrepreneurial spirit — he and his wife Janet founded Gig Harbor Boat Works in 1986.

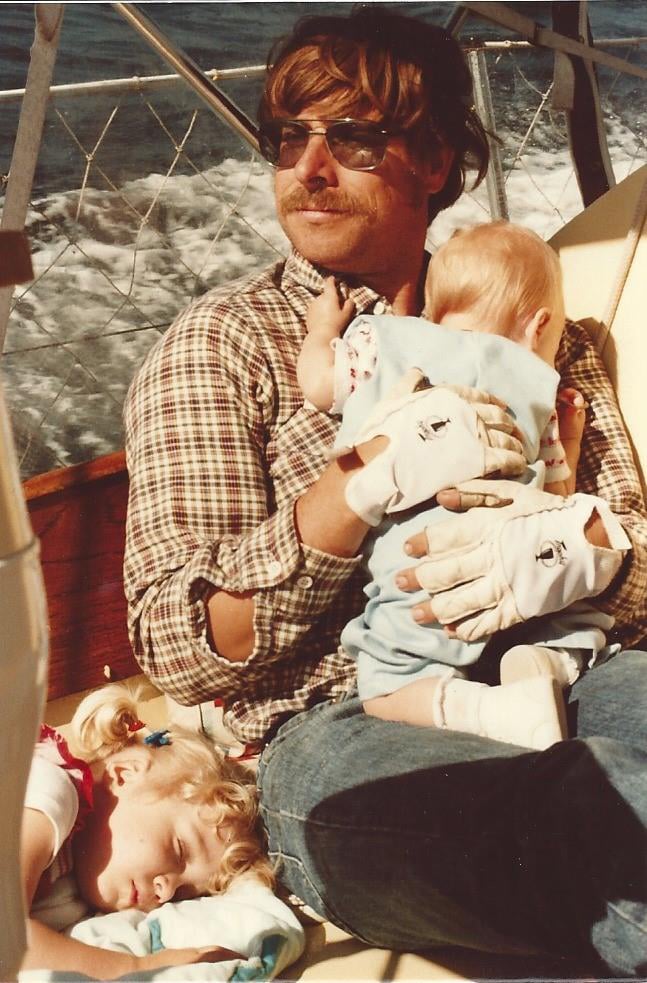

David Robertson in the early 1980s, with his daughters Jessica (asleep) and Katie (in David’s arms). Katie is now the general manager of Gig Harbor Boat Works. Photo courtesy Robertson family

Then he boldly signed up for a small space to show his creation at the Seattle Boat Show.

“I don’t know that I had any expectations,” he recalls now. “I thought if I was lucky I could sell a couple of boats” to help support his lifelong love of boat building.

At that show, he took orders for about two dozen of what he called his Ultralites.

Immediately, what he says was “strictly a hobby” became a business, competing for his time and energy with the other more mundane jobs he did to support his family.

Assortment of models

The Boat Works proved successful and gradually became a full-time endeavor. Yet he now says that it was not until the mid-1990s that he fully realized it was to be his life’s work.

Today, his first simple rowboat has evolved into a line of custom-finished, handcrafted small boats. Ten models vary in lengths from eight to 17 feet and are priced from $4,000 for the simplest to more than $32,000 for a fully tricked-out top of the line.

True to their origins, all but one model can be rowed, but most can also have sails and accommodate a small outboard engine.

Gig Harbor Boat Works’ 12-foot Scamp model on display at the Seattle Boat Show in February. Photo by Chapin Day

Company promotional literature proclaims: “Our boats are proudly made right here in Gig Harbor.”

Well, yes and, well, no.

Over the years, David Robertson has lived and designed them here. He refined the designs of classic dinghies and other row and sail boats while adopting and adapting modern materials and construction methods. Moreover, every boat was completed in and delivered from that little red building below his family’s home.

But, for the last several decades, the basic fiberglass hull of each boat was built on the far side of the Tacoma Narrows — originally in Puyallup, more recently in a 4,000-square-foot shop in a Tacoma industrial park.

That’s about to change.

Moving back across the bridge

Starting soon, Gig Harbor Boat Works boats will be built, start to finish, in … wait for it … Gig Harbor!

The company has already begun the transition, even while awaiting final city permits.

Furnishings and other trappings are beginning to pile up in a 2,000-square-foot office suite attached to the the firms’s new production center: A sprawling 10,500-square-foot facility comprising two adjoining warehouse-style spaces in the Northarbor Business Campus off Burnham Drive.

Gig Harbor Boat Works is moving hull production, final assembly and other functions to the Northarbor Business Campus off Burnham Drive. Photo by Chapin Day

One will house hull construction, the other final assembly and finishing details.

Boatworks General Manager Katie Malik, long accustomed to more confined quarters, enthuses as she leads a visitor along an office hallway, “Look, a conference room. And a bathroom.”

Malik, 44, David Robertson’s youngest daughter, took the helm of the business in 2021 when her father retired. Her dad, now 76, says he stands ready to offer counsel and advice “when asked.” He seems a bit wistful, but ultimately comfortable, as he describes “feeling further in the background all the time.”

Meet the new boss

On the company’s website shortly after he retired and left his daughter in charge, Robertson wrote: “Rest assured this isn’t a case of mere nepotism — in addition to being very familiar with our boats, Katie is a highly accomplished business woman in her own right.”

He credits her with helping spur business when she was a teenager by encouraging him to establish a website, then and now a key to the firm’s continued success.

For her part, Malik remembers that, when she was a young girl, her dad trained her to use a drill press to cut holes for oarlock fittings. She learned that and other boat-building tasks. But as she grew, she spent more time and schooling on other interests — in singing and music, plus a more financially practical interest in business.

Katie Malik is the general manager of Gig Harbor Boat Works, the second generation of her family to run the business. Photo by Chapin Day

She worked for 17 years with an IT company in Seattle before setting out on her own with a marketing firm. As things worked out, she says, her primary client became Gig Harbor Boat Works. Before long, she was formally an employee in the family-owned company.

A spike in demand

In 2021 she assumed command at a crucial juncture for the firm. The COVID-19 pandemic spurred an extraordinary rush of customers anxious for outdoor family activities like boating. Orders swamped Gig Harbor Boat Works and other manufacturers just as supply chains for materials dried up or became clogged.

The website she had helped encourage and contributed to over the years had proved effective in attracting clients from throughout the nation, even some from other countries.

That demand came with a downside. The waiting list for a new dinghy or other models grew from a “normal” target of three to four months to over a year and a half.

David Robertson’s daughter, Jessica, in one of the first Ultralite dinghies her father built. Photo courtesy of the Robertson family

For Malik, stabilizing the waiting list at sustainable levels has been just one chore among many, including planning the current manufacturing move, meeting the need for economical nationwide transport of new boats, and overseeing a merger.

In 2022, Gig Harbor Boat Works acquired Texas-born, now Port Townsend-based, Duckworks Boat Builder’s Supply. It was a logical teaming, she says, though not part of any broader expansion plan.

A changing market

Initially, Malik says, the firm’s current move-in will add only two local employees to current company payrolls of 12 in Gig Harbor and four in Port Townsend.

However, local consolidation of production, plus the more than doubling of space for it, leaves economic elbow room for growth in a changing small boat market. Local buyers were once key. Now, Malik says, only 40 percent of the 100 boats the firm sold last year went to Washington state owners.

Beyond that, a younger generation of boaters, less oriented to larger yachts — costly, difficult to find moorage for, and expensive to maintain — covet the larger end of her firm’s trailerable recreational boats.

Small dinghies, once dominant, are yielding production spots to their bigger siblings.

Historically, David Robertson says, classic dinghy and small boat builders worldwide were widely scattered “mom and pop shops,” struggling precariously for profitability in localized markets. “We were all mom and pops,” he recalls.

Gig Harbor Boat Works founder David Robertson at the business’s current facility on Peacock Hill Avenue. Photo by Chapin Day

Industry survivors

Over the years, bad management, bad planning, bad products, bad economies and even bad luck have winnowed the industry down to a less than a handful of notable builders.

As other maritime industry observers do, Robertson and Malik rank Gig Harbor Boat Works at or near the top of those survivors.

Against a marketplace that includes scads of cheap, mass-produced small boats, Malik credits that endurance to the quality of construction, durability, repairability, and esthetics of the firm’s classic products, all backed with a dedication to a personal style of customer service.

Each boat ordered is customized to the buyer’s specifications, including extra-cost items from a list of dozens of options ranging from $55 for a brass plaque to almost $3,000 for wood trim items on the largest models.

Offerings even include, for around $2,000, an electric outboard built by a North Bend company.

As one employee acknowledged to Gig Harbor Now, the boats are “especially expensive when you compare them to what you see at Costco, which are basically a couple pieces of thermoplastic stuck together.”

A boat that lasts

On the other hand, Robertson, grandfather of two teenagers, notes that in contrast to such flimsier or disposable craft, his firm builds “a heritage-type boat,” one meant to passed along to future generations.

That, he says, raises another justification for the expense: depreciation.

Online, he tracks re-sales of older Gig Harbor Boat Works craft. Often, he says, owners sell them for as much or more than they bought them for.

As he talked recently, seated at a picnic table outside the company’s original red building, his pride, though modestly muted, shows through.

In his 76 years, with the help of his wife Janet, he has built a heritage business, now in the hands of their daughter and other family members.

The red building on Peacock Hill Avenue that is home to Gig Harbor Boat Works. Photo by Chapin Day

Boats built by a boater

He began boat building at age 12 from a kit purchased in a magazine. Drafted, he served in the Army, including a 1968 to 1969 tour in Vietnam. He educated himself in boat design and business and launched and nourished his company.

“I always built boats that I wanted for myself,” he says.

Now, he says, he has time for other interests. An archer, he builds bows, plus he has more time for his interest in restoring vintage boats and automobiles.

And what’s going to happen to that red building at the foot of his driveway?

It will remain the public face of Gig Harbor Boat Works, remade in the interior as a showroom and sales office for all those boats yet to come from the new plant less than a mile away.

But it will retain a workbench or two, a bit of nostalgic decor to remind everyone of a bit of Gig Harbor maritime history.

Asked if he regretted not naming his business Robertson Boat Works or his dinghies Robertson Dinghies, he smiles and sighs a bit.

“I’d be better known if I had,” he acknowledged, “But for a business building gigs, what better name than Gig Harbor?”

Gig Harbor Boat Works customer service representative Fred Palmer works in the boat builder’s current facility. Photo by Chapin Day