Community Environment Health & Wellness

Jennifer Preston: All mushrooms are magic

They help turn wheat into bread and fruit into wine. They ferment cacao beans, making it possible for us to enjoy one of the world’s favorite treats — chocolate. They give us penicillin, forever altering the way we fight infection.

These mostly invisible, seemingly magical organisms quietly go about their work sustaining forests and enriching the soil. Without them, life as we know it would cease.

Phenomenal fungi

Mushrooms have a rich history spanning many cultures and traditions. For thousands of years, they’ve been used as food, medicine and in spiritual practices. Perhaps soon, they will be a replacement for plastic and even building materials.

Their abundant appearance in art and folklore reveals their popularity. Yet somehow, they manage to retain an air of mystery. Perhaps this is because, depending on the species, they will either sustain and heal, bestow hallucinations, cause severe illness or kill you. (Consider for a moment that the mushrooms capable of the above effects can all look deceptively alike.)

Mushrooms break down natural materials like logs and leaf litter, recycling the forest floor into food for themselves, plants and animals. If these fungi foodies weren’t constantly at work chewing up dead things, our forests would be buried under a mountain of un-decomposed trees and animals. Soil would be depleted of nutrients and become infertile.

What lies beneath

Mushrooms are members of the fungi kingdom and more closely related to animals than plants. Their stunning variety of shapes and colors are the visible fruiting body of mycelium (mai-SEE-lee-uhm), which spread just below the soil surface.

To compare these parts to a plant, the mushroom is like the flower whose job it is to make seeds to reproduce; while mycelium are the roots signaling when to blossom and sending nutrients.

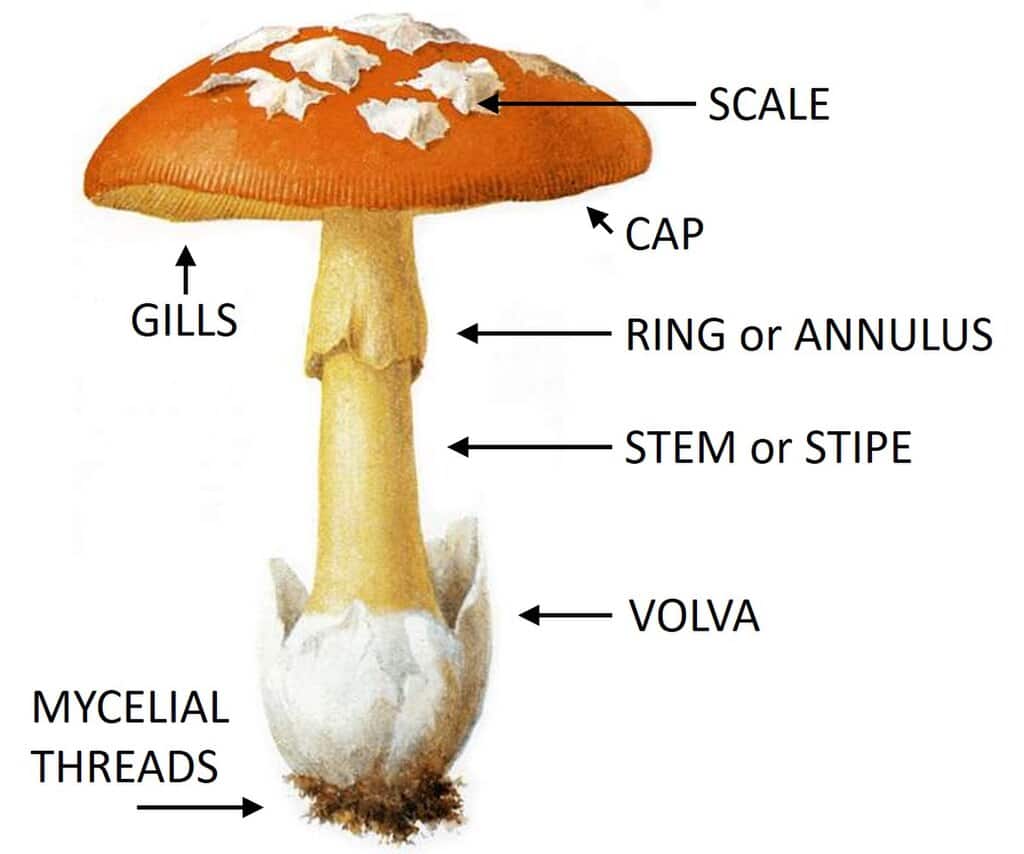

Anatomy of a mushroom

Attribution: Zhousun21, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mushrooms have no chlorophyll and cannot use the sun’s energy to photosynthesize like trees and plants. Their mycelium, made of tiny filaments called hyphae (hai-fee), reach out and wrap around nearby roots to receive carbohydrates (sugars). In exchange, they provide their partner trees and plants with nourishment like nitrogen and additional water beyond their reach.

The original social networkers

When mycelium connect to tree roots in a symbiotic relationship to exchange nutrients, they create what’s called a mycorrhizal (mahy-kuh-RAHY-zaul) network, from the Greek words for fungi (myco) and root (rhiza). Mycelium is tiny, but you may see its white threads spreading along a root ball or under a log.

This cross-kingdom underground connection between mushrooms, trees and plants is an ancient World Wide Web, or more aptly described as the Wood Wide Web. Mycelium sense changes in the environment, like temperature drops and rain, then respond by sending signals to grow mushrooms, direct nutrients to a particular tree and more. This interaction allows fungi to feed, grow and partner with vegetation that can photosynthesize.

According to mycologists, 70-90% of trees and plants have a symbiotic relationship with mycelium. In fact, some plants need very specific fungi to germinate and grow. Climate change, the loss of woodland habitats and heavy land use threaten these important relationships.

Oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) mycelium growing on coffee grounds. Photo by Tobi Kellner, via Wikimedia Commons

For example, Kew Gardens writes that the “Lady Slipper Orchid is now so rare in the UK, that just one individual plant remains in the wild and it’s protected in a top-secret location.” They’re working hard to save this species by identifying its perfect fungi friend. To learn more about this special unground connection, watch What Is Mushroom Mycelium? on the Host Defense website.

Fungal fruit health benefits

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has utilized mushrooms’ antibacterial and antiviral aspects for thousands of years. Thankfully, mushrooms are getting the attention they deserve in the West with books and documentaries, like Fantastic Fungi, which explore their health benefits and healing properties alongside dozens of official studies revealing their incredible ability to reduce inflammation, fight cancer and much more.

This is an exciting time in the mycological world as scientists discover exactly how particular species work to help us fight disease and regain health. For example, certain bioactive components in mushrooms like polysaccharides and terpenoids have a positive effect on brain health. Their neuroprotective abilities fight neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s.

Many companies are offering the benefits of mushrooms in capsules, powders and tinctures now. Paul Stamets, our famous local mycologist, has probably done more than any other to popularize their many uses, attracting the attention of the medical field, pushing for more research while he conducts his own. Finally, more and more people are paying attention.

Stamet’s company Fungi Perfecti based in Olympia lists helpful information, links to research and learning resources. They also sell grain spawn so you can try growing mushrooms at home.

Photo by Jennifer Preston

The future is fungi

The Cradle to Cradle philosophy models the fact that nature doesn’t create waste. In the book Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, architect William McDonough and chemist Michael Braungart argue for an integration of science and design that emphasizes safe materials and circular economies with zero waste.

In nature, everything is recycled and no pollution is created. It is a perfect, circular system, where the “waste” of one is useful for another. For example, a decaying log is food for fungus and critter habitat.

Evocative Design is a collection of engineers, geologists, biologists and mycologists working together to uses mushroom technology to create alternatives to plastics and polystyrene foam packaging, which take a long time to break down, if ever.

Using agricultural waste, like corn husks from local farms, the material is chopped up, cleaned and inoculated with mycelium. Within days, it quickly forms a matrix, taking on the shape of any mold its placed in, creating a compostable alternative to Styrofoam.

In 2020, Ikea committed to replacing all of its polystyrene packaging with natural materials using Ecovative’s tech, and hope to be completely plastic-free by 2028.

The same process can also be used to grow building materials. The company says that the bio-based material has no synthetic chemicals and emits no volatile organic compounds.

Imitate to eco-vate

Biomimicry looks to nature for intelligent design solutions. For example, the company Biohm developed bio-based building insulation using mushroom mycelium. This innovative process was inspired by nature’s nutrient cycles and results in fewer cut trees, less CO2 emissions and more. Biohm states that it is driven by “the simple philosophy of allowing nature to lead innovation and only having a positive, or regenerative, impact on everything we touch.”

Along with other companies, Biohm is investigating uses for mycelium because it is incredibly adaptive. Its fibers are made from proteins, sugars and chitin (the stuff that makes lobster/crab shells), which will grow into the shape of any container you place them in. “This structure makes them strong, flexible, compressible, expandable, moldable, and durable,” writes Biohm, “a highly desirable combination of traits that provide inspiration for innovative design of packaging, clothing, insulation, and more.”

Mycelium cast into brick shape at Genspace, a community biology lab in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Photo by Rhododendrites, via Wikimedia Commons

As the population continues to expand and Earth’s resources are stretched ever further, it’s imperative we develop substitutes to materials made from animals, non-renewable sources and explore safe, sustainable building materials for current and future generations.

Bolt Threads created a mycelium-based alternative to animal leather called Mylo, which is just as soft and supple. They’re working alongside companies like Lululemon, which are investing in product development in exchange for hundreds of millions of square feet of the mushroom material. Adidas sneakers and Stella McCartney handbags made from Mylo debuted in 2021. As of this article, they paused manufacturing their leather alternative until they secure more funding to scale production.

Grow your own mushroom house

Ecovative built a tiny house from mushrooms to prove the potential and explore using the material as a replacement for structural insulating panels. The Mushroom Tiny House walls are tongue and groove pine boards packed with their live Mushroom® Insulation.

Within just three days, “the mycelium grows and solidifies…into air sealed insulation, while also adhering to the pine boards creating an extremely strong sandwich.” Over the course of about a month, the insulation naturally dries and goes dormant. (Given that the material is “dormant” rather than heat-treated and killed, I wonder if it reactivates does that mean you get to snip fresh mushrooms sprouting from your walls for dinner?)

On top of being eco-friendlier that traditional building materials and creating less waste, Ecovative says the price is comparable and often cheaper. Here’s a short video of Ecovative’s Mushroom Tiny House design.

Fungi filters

Matt Ferrell discusses other advantages of mycelium in “Is Mycelium Fungus the Plastic of the Future?” for his YouTube channel, Undecided. He shared the disturbing fact that we consume about 5 grams of plastic every week, which is about the same weight as a plastic bottlecap or enough to fill a ceramic soup spoon.

Discovering and implementing cheap toxic waste clean-up and healthy alternatives to plastic cannot come a moment too soon.

The use of mushrooms and mycelium as filters for oil and toxic waste clean-up is being explored since they have an ability to digest and transform pollutants into inert substances. Called “mycoremediation” the methods utilize mycelium to treat contaminated soil. The enzymes produced by a mushroom are efficient in breaking down a lot of different pollutants.

Stamets placed oyster mushroom mycelium on a pile of diesel-contaminated soil alongside controls. His experiment showed that the mushrooms not only cleaned up the petrochemicals, they thrived, attracting insects and then birds, which brought seeds that became plants. The former toxic waste pile was transformed into “an oasis of diverse life.”

Next Wednesday I’ll share more news about the exciting, diverse mushrooms found locally and offer tips on how to safely forage for edible varieties.

Jennifer Chushcoff

Jennifer Preston Chushcoff of Gig Harbor is a writer, designer, former Master Gardener and self-described eco-advocate.