Community Environment Government

The Battle for Carr Inlet pitted local community against the Navy

Think the fight against Walmart in the 1990s, or the more recent flap over building 35 new dwelling units at the bottom of Harborview Drive, stand as the biggest citizen crusades in peninsula history?

Those were minor disagreements when compared to the Battle for Carr Inlet, fought in the early 1950s.

Decades before the term “NIMBY” joined the lexicon, Gig Harbor and Key Peninsula residents and their allies rose up and attempted to squash a U.S. Navy proposal to create a permanent operating area in local waters. Residents flooded public meetings in Purdy and Tacoma. They threatened lawsuits, sounded themes of states’ rights, and even discussed civil disobedience.

The fight over the Navy’s plans to use Carr Inlet as an acoustic range generated dozens of headlines in the 1950s.

Locals object to Navy’s Carr Inlet plans

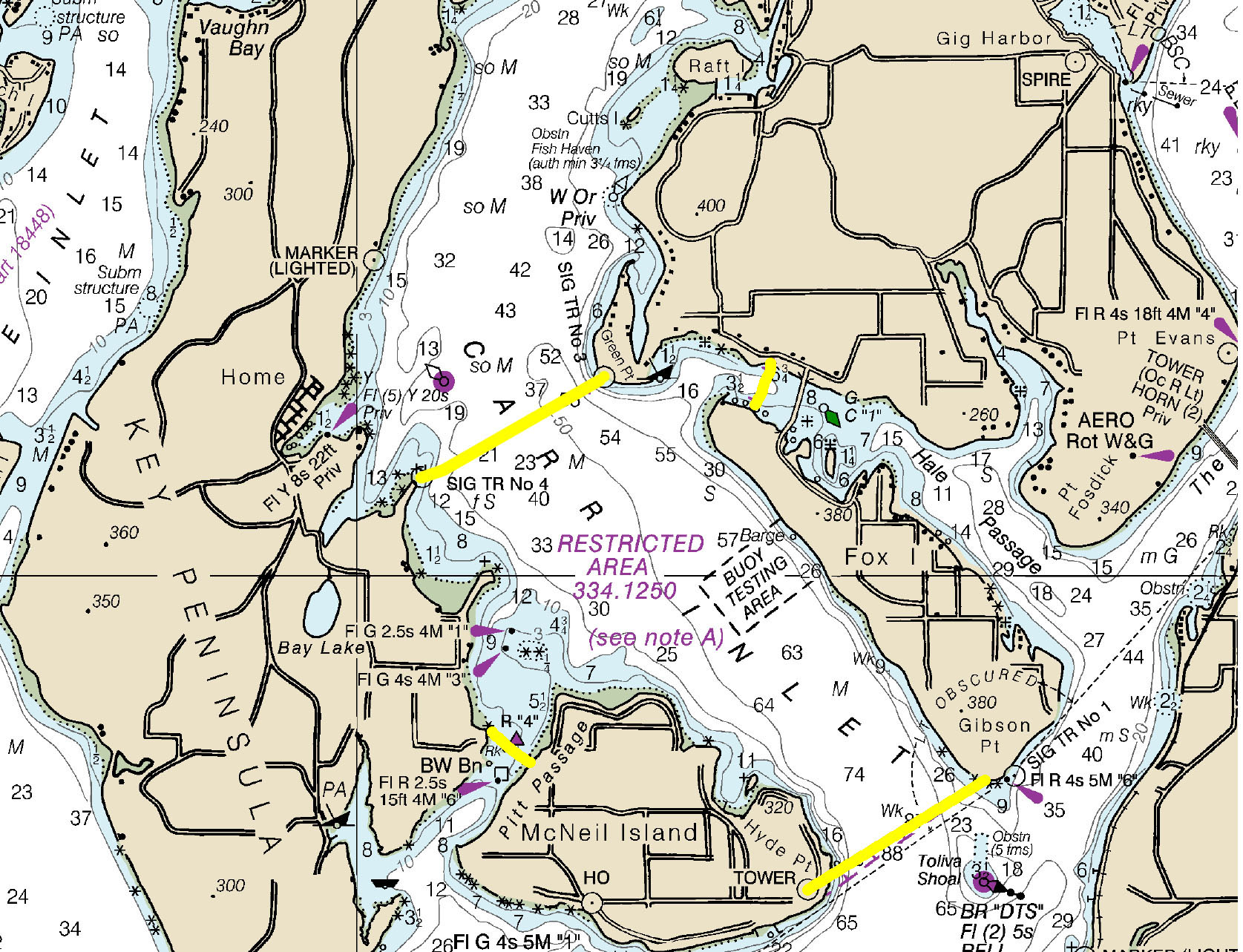

The news hit on Aug. 31, 1952, that the commandant of the 13th Naval District had applied for a restricted zone in Carr Inlet. If approved, the new Carr Inlet Acoustic Range (CIAR) would be closed to civilian boaters for about 150 weekdays per year. The range comprised the waters between Fox Island and McNeil Island, northward to a line between Green Point on the Gig Harbor Peninsula and Penrose Point on the Key Peninsula, and included portions of Hale Passage and Pitt Passage.

On those 150 days, Navy scientists would test the noise made by submarines and other vessels, reports said.

Peninsulans and others who depended on Carr Inlet howled in protest. The closure would bankrupt businesses related to boating and fishing and send property values on the peninsula plunging, they said.

Opponents warned of a resulting economic downturn that would torpedo the bonds that financed a new Tacoma Narrows Bridge and prevent construction of a Fox Island Bridge. The proposed range would cut off Key Peninsula farmers from their markets; bargemen would lose favored areas to wait with their log booms for a change in Tacoma Narrows tides.

‘Beyond all sense or reason’

The story vied with Cold War intrigue for space on local newspapers’ front pages. Average citizens found themselves opposing a branch of the U.S. military in an age that, by-and-large, was wary of such dissent.

“All Tacomans as well as citizens of the areas affected ought to protest this outrageous proposal,” the Tacoma News Tribune editorialized. “While the state and Pierce County are trying to develop this area by building bridges and opening up the country, the Navy proposes to seal it off.”

“The Navy’s plan to monopolize for 150 days of each year the area involved is beyond all sense or reason,” the Peninsula Gateway thundered.

The Tacoma paper’s front page story predicted that a Sept. 30 hearing where the Army Corps of Engineers would review the plan “will be inundated by a tidal wave of angry and highly vocal delegations from Puget Sound cities and property owners protesting the Navy’s plans for Carr Inlet.”

A crowd estimated at 500 showed up for the meeting, where officials made impassioned pleas against the plan. Yet the Corps approved it — the first of several sign-offs needed by the Navy.

Navy found site ideal

January 1953 brought a hearing in Washington D.C. on the issue. The Navy agreed to re-survey possible alternative locations.

But Washington Rep. Thomas Pelly said publicly that approval of the range in Carr Inlet was likely. He cited Navy sources who told him the location was ideal for testing, with the needed depth, shelter from winds, lack of some forms of disruptive sea life and overall quietude. Most important was its proximity to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton.

This image, taken from a public U.S. Navy video, shows the submarine USS Richard B. Russell in the Carr Inlet Acoustic Range near Fox Island.

In a last ditch effort, Tacoma Mayor John H. Anderson appealed directly to President Eisenhower by telegram, urging Ike to “Save Carr Inlet from the Navy,” the Bremerton Sun reported on April 29.

“Two hundred thousand people in the vicinity object to the navy’s possessive high-handed tactics in appropriating the waters of Carr Inlet,” the Sun quoted the telegram as saying. “We have spent $14,000,000 on a bridge and are spending $1,500,000 on another bridge to develop the area which will be cut off by the navy’s action. At least 20,000 are directly affected by the restrictions.”

“We appeal to you to help us keep our natural resources that are rightfully ours and motivated our settling in the area.”

A slippery slope on Fox Island?

Lyle Iversen, former assistant state attorney general and legal counsel for the citizens’ “Save Carr Inlet” committee, explained to a reporter that while “suing the United States is not easy,” an effective strategy might be to have someone get arrested for violating the acoustic range boundaries. Lawyers on that case could challenge the restrictions in court.

Iversen warned of future federal grabs. “We should not consider Carr Inlet alone in this matter,” he said. “There are many areas in Puget Sound endangered by this creeping paralysis. The fact is that the Navy is no different from other government bureaus. Bureaucrats do everything for their own convenience.”

This undated image, taken from a publc U.S. Navy image, shows technicians working in the Carr Inlet Acoustic Range.

Final approval of the plan arrived in May 1953. Talk of lawsuits against the federal government continued for some months but came to nothing.

In late summer, the USS Bashaw, a Pacific Fleet submarine, became the first subject of acoustic testing in Carr Inlet. It sailed up the coast from California as Navy contractors finished laying the needed underwater power lines and putting final touches on shore-based beacons, including one near Home on the Key Peninsula.

Range was never as busy as Navy warned

In the ensuing months and years, the range grew busy — though it perhaps never reached the full 150 testing days per year. Locals simply planned around Carr Inlet closures.

The restrictions softened somewhat from what local papers first reported. In addition to limiting testing to just 150 weekdays per year, the Navy stated it would close Carr Inlet only from 9 a.m. to noon and 1 to 4 p.m.

During active periods, commercial vessels could transit the range provided they gave adequate notice. Other small powerboats used frequent opportunities to pass through. Non-motorized craft could stay in the restricted area at all times during testing, as long as they kept to shore lanes created for that purpose.

The Navy operated its acoustic range off Fox Island for almost 40 years before moving tests to a new site in Ketchikan, Alaska. To learn how the Navy’s facility on Carr Inlet is getting a new life, look for our story on Friday, July 7.