Community Environment Government

Stronger shoreline protections on county council’s docket

Derek Young, as his term nears its end, is close to achieving something he sought when he became a Pierce County councilman eight years ago — stronger shoreline protections.

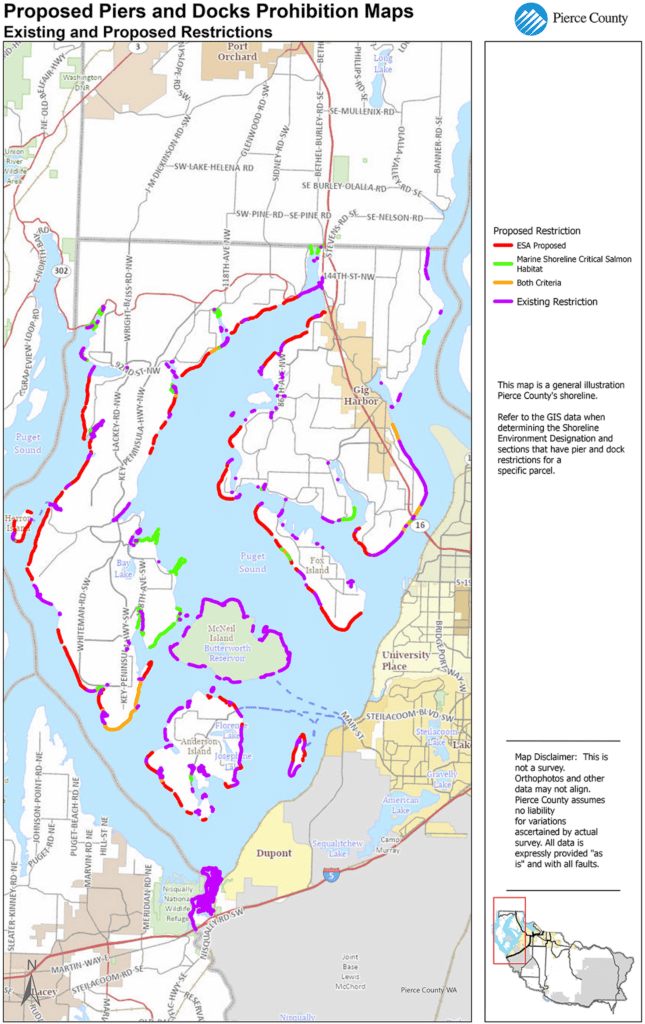

The council’s Community Development Committee, of which Young is a member, passed updates last week to the Shoreline Master Program. The most significant would restrict new residential pier and dock construction along an additional 49.2 miles of saltwater beach that possess specific environmental and habitat features.

The proposal goes to the full council on Tuesday, Dec. 13, for final approval. It would become effective 14 days after the Washington State Department of Ecology gives written notice of final action.

Proposal protects 49.2 more miles

“The reason I’m doing this is the same reason I ran for office 25 years ago,” said Young, who served on the Gig Harbor City Council from 1998 to 2014 before being elected to the county post. “To protect this place we all call home and love.”

Some 75.8 miles of Pierce County’s 180 miles of shoreline, most of which borders the Gig Harbor and Key peninsulas and Fox Island, is already off limits to new residential docks and piers. That shoreline performs irreplaceable ecological functions or is reserved for commercial use.

Of the 49.2 new miles, 19.1 would comprise areas already defined as Marine Shoreline Critical Salmon Habitat. The county instituted a substantial setback for building on the land, but placed no limits on the beach.

“That is another part of the puzzle that makes no sense,” Young said. “Somehow a previous council applied that marine critical habitat designation, but decided they didn’t want to impact people who wanted to build docks, so it only applied to upland development. That was strictly a political decision. It is not based on science.”

County policy doesn’t line up with state’s

The state and counties jointly administer shoreline plans. But it quickly became apparent to Young that Pierce’s was more lenient and in conflict. It doesn’t do enough to prevent loss of critical habitat for forage fish, migrating salmon fry and eel grass, or address high banks that recharge nutrients into Puget Sound.

“The (Planning and Public Works) department’s interpretation is significantly different than ours in what needs to be protected,” Young said. “If you read the rules of the state Shorelines Management Act, and what our own science tells us, our protections need to be pretty robust.”

At the same time, as waterfront in protected bays got snapped up, people began to apply for dock permits on weather-exposed shorelines where nature had previously deterred them.

In 2019, the county hired Environmental Science Associates to conduct an analysis, based on best available science, of potential amendments to the regulations.

ESA recommended a ban on piers, ramps and floats on 38.8 miles of shoreline that contain highly intact ecological functions, relatively few overwater structures, options for public access or recreation, unstable slopes, high nearshore tidal currents and wide tidal flats.

Proposal went from 38.8 to 7.3 to 49.2 miles

Planning and Public Works issued a Determination of Nonsignificance on the 38.8-mile increase in October 2021. In March, after public outreach, it reduced the mileage to 7.3 miles in a revised DNS.

The Puyallup and Nisqually tribes, who are entitled to half the fish in their usual and accustomed harvesting grounds, disagreed with the proposal and joined the discussion in April. Through consultation with them, the state Department of Fish and Wildlife and county staff, plus input from four Community Development Committee public hearings, the mileage was increased to 49.2. (There is about an 8-mile overlap of the 38.8-mile ESA and 19.1-mile critical salmon habitat areas.) The county sent notices to 1,852 affected waterfront property owners and other interested parties.

The county received a mixed reaction during public hearings, Young said. Some property owners want to preserve the right to build docks and piers. Others who have a front-row seat to a changing Puget Sound are uniquely aware of the need for protection.

“People are increasingly disturbed by a lot of different kinds of development on the shoreline,” Young said. “I think the vast majority of the public want to do the right thing to protect what we have because it’s special, it’s why we live here.”

Docks confined to where most already are

New restrictions would affect much of Henderson Bay, and the west sides of Fox Island and Key Peninsula, confining docks and piers to more protected waters where they already exist. Where allowed, they’d still need to be feasible for the site.

“In places already highly disturbed like bays, it’s not going to make much of a difference,” Young said. “Where we have undisturbed shoreline still intact, we need to protect. (Docks and piers) need to go somewhere, and we don’t want them to go into natural, low-intensity environments. It’s very similar in a lot of ways to the Growth Management Act. In order to protect these other areas, we’re going to encourage development in these already-impacted areas.”

Time is running out on saving Puget Sound, Young said. Drastic measures are needed.

Hugging Puget Sound to death

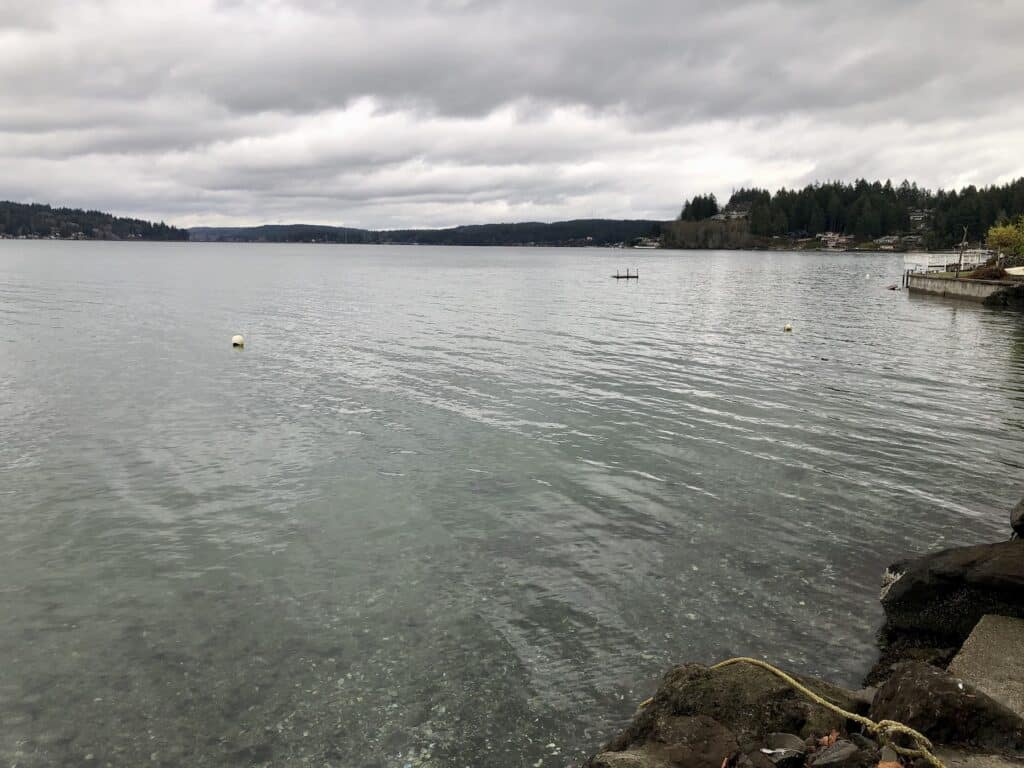

“We are at this point now where we are hugging Puget Sound to death,” he said. “We are over-loving it. Individual impacts may not be that great, but cumulative impacts are devastating, so we have to reverse that trend.”

Orcas, at the top rung of a food chain that relies on a healthy Puget Sound habitat, captivate people. We might be among the last generations to enjoy them, or to even take our kids fishing in Puget Sound, Young said. “That’s heartbreaking. We have a moral obligation and a legal obligation to figure out ways to turn this around.”

There are already many docks on Hales Pass between Fox Island and the Gig Harbor mainland, and new ones will continue to be permitted.

Committee member Paul Herrera said salmon must “run a gauntlet” to swim from the far South Sound to the ocean and back.

“We’ve already lost habitat in the Puget Sound forever,” he said. “It’s happening now. This is a great opportunity in the South Sound to preserve what we have.”

Nobody spoke against amendment

Committee Chairman Ryan Melo concluded, “These are exactly the kinds of actions we need to be taking at the local level to improve the health of Puget Sound.”

Nobody spoke against the amendment during a Dec. 7 public hearing. Puyallup Tribe Land Use and Planning Director Andrew Strobel, and Tahoma Audubon Society’s Kirk Kirkland, Eric Seibel and John Garner gave support.

The committee passed two other amendments. One would prohibit piers and docks along 2.8 miles of Browns Point and Dash Point shoreline. The other would allow non-commercial aquaculture for native species recovery.