Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | If only they had followed their own advice

Our previous question of local history began with this setup explanation: In the spring of 1921, many grade school students on the Gig Harbor and Key peninsulas participated in a countywide essay contest concerning the harm caused by smoking tobacco. Victor Heiman of Lakebay placed in the top four countywide, while the four best essays from Wauna School were written by Belle Blakeslee, Walter Luters, Mildred Lofgren and Edward Lofgren.

How many of the five did not die from smoking-related diseases?

Answer: one.

Victor Heiman died of lung cancer at age 72. Walter Luters died of lung cancer in 1966 at age 61. Ed Lofgren was a smoker and died of smoking-related causes, including tongue cancer, in 1993, at age 84. Mildred Lofgren (married names Bjornson & McLean) was a smoker for over 50 years, and died of lung cancer at age 82.

Only (Jessie) Belle Blakeslee (married name: Theis) didn’t die of smoking related causes. She was not a smoker, and lived to be 90.

When The Bay-Island News reported on the essay contest, it said it would be printing the winner of the Wauna School entries, but I never found it. Too bad. It would’ve been interesting.

Another editorial opinion

Our next column, on October 7, is a very long one. To prevent it from being even longer, there will be no question this week that would have to be answered next time. Normally, that would result in a shorter-than-average column this week (was that a collective sigh of relief I heard from the gallery?), which would run the risk of creating an imbalance in the Gig Harbor Now and Then chi. You can’t have that in a history column. It would interfere with an objective reporting of the past, if not also create disruptive irregularity.

So, to balance the chi and avoid spiritual calamity, instead of setting up a new question, we’ll fill out the remainder of this column by falling back on that familiar old crutch, the editorial opinion. (Which, interestingly enough, appears in this column with disruptive irregularity). The subject is age, which is very appropriate for a history column.

How old are you?

When you ask people how old they are, the answer you get is influenced by the age of the person you’ve asked. There are definite variations between the low and high ends of the scale.

Kids under, oh, 7, maybe, will often add a half year to their answer. “I’m five and a half!” They’re excited to be getting older. A half a year is a pretty significant percentage difference, so it makes sense to include it.

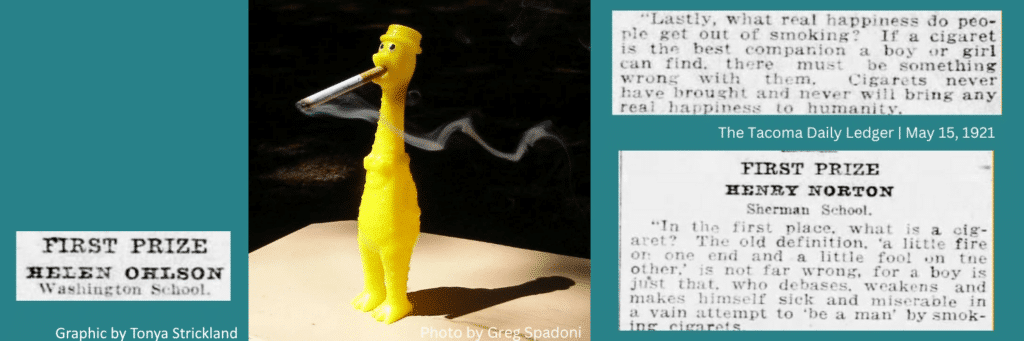

Five and a half is a milestone worth celebrating. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

After age seven or so, you generally get a straight answer to the question, at least until middle age, when a select category of a certain gender doesn’t like to be forthcoming.

At the far end of the age range, people over 60 or thereabouts won’t tell you how old they are. You can ask, but they won’t reveal it. Instead, they insist on telling you how old they’re going to be:

“Hey, Schmidlap, how old a man are you?”

“I’m going to be 77, come October.”

Ask a middle-aged person how old their mother or father is, and they slip into old-age-speak too. “Mother’s going to be 86!”

Yeah, well, so are you, someday.

As opposed to the 5-year-old who, in unbridled excitement, adds a legitimate half year to their age, elderly people tell you how old they’re going to be, just to brag. There’s no other reason. That’s not to say there’s anything wrong with bragging. After all, living to be a wrinkled old prune is quite a feat. But at the same time, telling only how old they’re going to be is inconsiderate. Instead of answering the question, they give you just enough information for you to figure it out for yourself, then make you do it.

A different way to ask

There is a way to make people tell you their present age, however, if you can’t quite do the calculation in your head (or simply refuse to). It takes twice as long, because it involves a second question, so it’s not a quick solution. It relies on pretending you can’t subtract one year from the number you’ve been told. (Most people wouldn’t want to appear that dumb, but then again, most people wouldn’t write about this subject in a local history column, either.)

The least you could do is give it a try.

The next time someone tells you how old they’re going to be, low-ball ’em:

“I’m going to 89 on my next birthday!”

“Congratulations! That means you’re what, 83 today?”

Remember, when someone tells you how old they’re going to be instead of how old they are, they’re bragging. They’re not about to let you think they’re five years younger than they really are. They’ll correct you in a heartbeat. That’ll save you from having to do that complicated minus-one calculation.

A reversal

You could also turn it around and put the burden on them:

“I’m going to be 90 later this year!”

“Great! How old will you be four and two-thirds years from a week ago, last Monday?”

Or you can appear to be even more daft, just for fun:

“I’ll be 83 this year!”

“Really? You don’t look a day over a hundred!”

One big candle is sometimes used to celebrate a one-hundred-year-old’s birthday. It would probably be better to use a full-sized cake than a cupcake, though. It’s less likely to tip over. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Graciousness is better than an insult

Because old people not telling their present age is such a minor, nitpicky thing, there’s no cause for being downright insulting, no matter how much truth is in your response:

“Looks like I’ll finally make it to 80 this year.”

“Well, I hope you celebrate by finally taking a bath.”

Even when armed with alternatives, it’s almost always best just to suck it up, do the subtraction in your head, and be gracious about it:

“I’ll be turning 75 next year!”

“Good for you! That’s quite a milestone. I’m happy for you.”

It would also be gracious of them to say how old they are when they’re asked, instead of bragging about how old they’re going to be.

Filler of the week

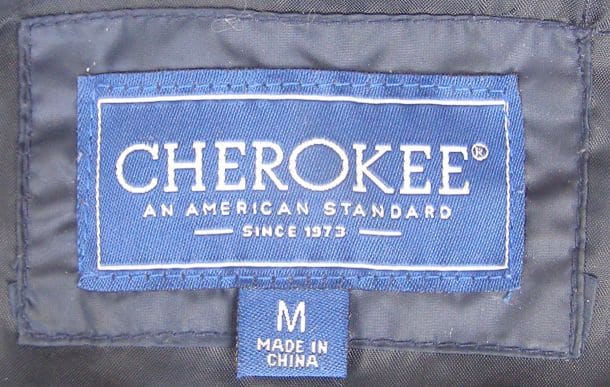

To slightly lengthen this week’s rather short column, we have feeble filler. It’s feeble only because it’s so short. It does have substance, just not in a wordy sort of way. And it follows the theme of history, going all the way back to 1973.

Is it obvious that the following question is rhetorical?

What’s wrong with this picture?

Next time

In Gig Harbor there are a series of stainless steel plaques mounted on several concrete pylons in various spots, reaching from the intersection of North Harborview Drive and Austin Streets to Austin Park. They tell the history of the Swiftwater Tribe on the land upon which the pylons stand. One of the plaques in Austin Park says, of Gig Harbor’s Native Americans, “Unfortunately, as settlers continued to arrive, the sx̌ʷəbabš were ultimately pushed off their homeland and onto the newly established Puyallup Reservation.” Since those plaques were placed in the park, we’ve discovered that’s not what really happened.

Our next Gig Harbor Now and Then column, on Oct. 7 (in time for Indigenous Peoples’ Day one week later), will explain how the Gig Harbor Swiftwaters ultimately left their ancestral homelands at the mouth of Donkey Creek. It’s a very interesting story of a series of unexpected events, and one that’s never before been told anywhere. That makes it a Gig Harbor Now exclusive.

— Greg Spadoni, September 23, 2024

(I’ll be turning 135 … someday.)

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.