Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Right Hand Peninsula would’ve been a better name

As we noted in our previous column, the Key Peninsula was named in 1931 through a contest organized by several local businessmen. The winner, Edward M. Stone of Lakebay, submitted the name “Key.” That, added to “peninsula,” of course resulted in “Key Peninsula.” Our new question has to do with the runners-up:

What were the two runner-up entries in the contest to name what is now the Key Peninsula, and who submitted them?

Answer: Billy Sehmel spilled the beans half a day after the question was posted to the Gig Harbor Now Facebook page. It was a display of graciousness on his part, waiting for many hours to let someone else take a crack at it before it became clear there were no other takers. He also issued a challenge, which we’ll address at the end of this column.

The second place winning name was “Arcadian,” from Mrs. Doris Bolton of Vaughn, which earned her $15. The name is quite appropriate, and if Mr. Stone hadn’t come up with “Key,” we’d now know the area as the Arcadian Peninsula.

If neither Mr. Stone nor Mrs. Bolton had submitted names, the Key Peninsula would now be called Pensylvia. Nelson Peck of Vaughn was responsible for that one. It’s no coincidence that he had a five-year-old daughter named Sylvia at the time. His third-place entry paid $5.

There were five additional runners-up, but their submissions have not survived the passage of time. O. Owens of Lakebay, J. K. Munson of Olympia, Mrs. W. I. Palmer and Mrs. M. E. Van Slyke, both of Vaughn, and Otto Kemp of Gig Harbor each won a single dollar for their entries.

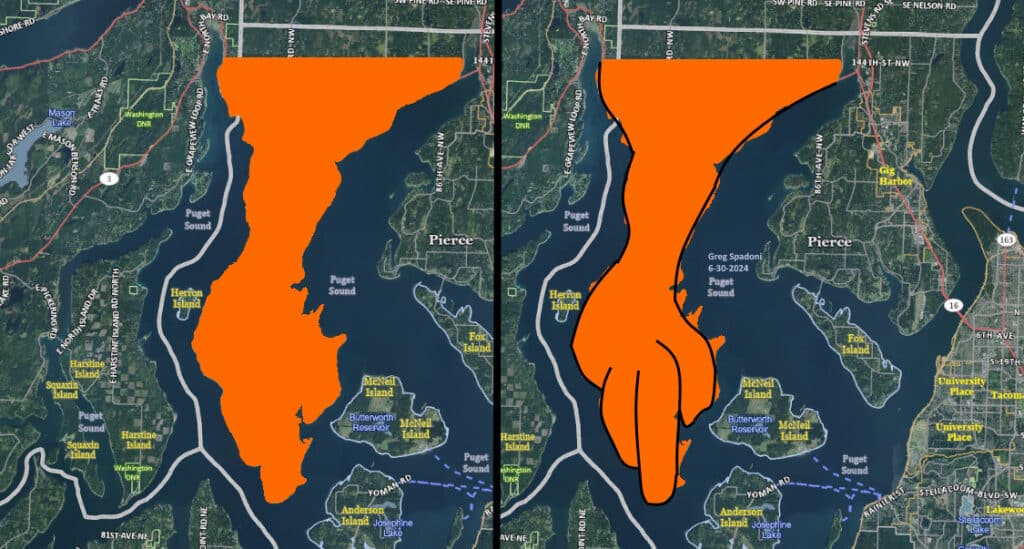

Key Peninsula or Right Hand Peninsula? Does the Key Peninsula really look like a key? (One run over by a freight train, maybe.) Or does it look more like a gnarled right hand, with its index finger pointing due south? Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

A slow adoption

Joseph Pentheroudakis of Herron Island, who brought this subject to my attention a couple years ago, points out that “the name Key Peninsula wasn’t officially recognized until 1979, when it was approved by the US Board on Geographic Names. Washington followed suit in 1980. That was done in connection with the plan to extend the countywide street numbering grid to the peninsula, which was implemented in the 1980s. While the name Key Peninsula had been used locally since the contest, it continued to be variably known as the Lower Peninsula or the Longbranch Peninsula in newspapers.”

Speaking of geographical names, the first installment of Joseph’s two-part series on the many fanciful theories on how Filucy Bay in Longbranch got its name was published in the current edition (July, 2024) of the Key Peninsula News. Part 2 will appear in August.

A future naming contest

Just because a place has been named once doesn’t mean it can’t be renamed. There are many examples of that having been done in the past, these being just a few: Balch’s Cove became Glencove, Springfield changed to Wauna, Clifton is now Belfair, Bremerton used to be Port Orchard, and Port Orchard used to be Sidney.

There may come a day when a majority of the residents of the Key Peninsula tire of its name. No matter the reason, they may someday be on the lookout for a new one.

Looking ahead to a new naming contest that may or may not ever happen, we can venture a guess at a winning entry, with logic and deductive reasoning leading the way.

By combining the past and the present, keeping in mind the large presence of Scandinavians all over the early greater Peninsula, and considering the dominant position Gig Harbor has taken in the section of Pierce County west of the Narrows, an entirely reasonable submission might be “Gig Harborson.”

That ought to be worth twenty-five bucks, huh?

Although as a practical matter, $25 wouldn’t even begin to cover the cost of removing the tar and feathers.

Filling time in the olden days

We’re presenting the following tiny slice of local history as an example of how Peninsula kids had to scramble to find things to do in their spare time 50 or so years ago. In the days of unfettered freedom, which was great, it wasn’t always easy to find something interesting to do. With the absence of home computers, the internet, cell phones, cable TV, year-round sports, a movie theater, or even a local fast food place to hang out at and be cool, Gig Harbor and Key Peninsula teens were left largely with improvisation. The results were not always satisfactory.

This little tale of failure will not inspire any young people today to try to repeat it, for two reasons. One, it’s highly unlikely anyone under the age of 60 reads this column, and two, the event is impossible to duplicate today. Nobody can repeat it because the location no longer exists.

A dim 4th of July

In 1973, there were not as many organized activities for local teenagers to do as there are today. Practically none, really. That could sometimes lead to trouble, but it didn’t have to. For a quartet of Peninsula High School students, having nothing to do on Independence Day that year didn’t lead to any trouble, but neither did it result in anything worthwhile.

The evening of the Fourth of July started for the boys with a familiar conversation. One of them said, “So, what do you want to do tonight?”

That was answered by one of the others with the predictable, “I don’t know. What do you want to do?”

Repeat that exchange several times and you’ll get an idea of how slow many summer evenings started for that group.

Dennis Hacker, Jim Grady, Mike Tarbet, and one more classmate, all 17 years old, couldn’t decide how to spend the evening of the Fourth until one of them came up with a plan that sounded pretty good on the face of it. They had no way to know that it would turn out to be a stupid idea in the end.

Don’t try this at home

The proposal was that after dark, they all climb one of the 317-foot Tacoma City Light power line towers at Point Evans on the Narrows. Since the night sky was expected to be clear, from the platform on top they would have an unobstructed view of all the municipal fireworks displays from north to south, as far as the eye could see.

Sounds pretty cool, huh?

It wasn’t.

Also known as the Cushman power line towers, they held up the original high-voltage cables that spanned the Narrows from the Gig Harbor side to Tacoma, delivering electricity from the Cushman hydroelectric dam on the Olympic Peninsula. There were two towers on either side of the water. They were replaced in 2006 by a single tower on each side.

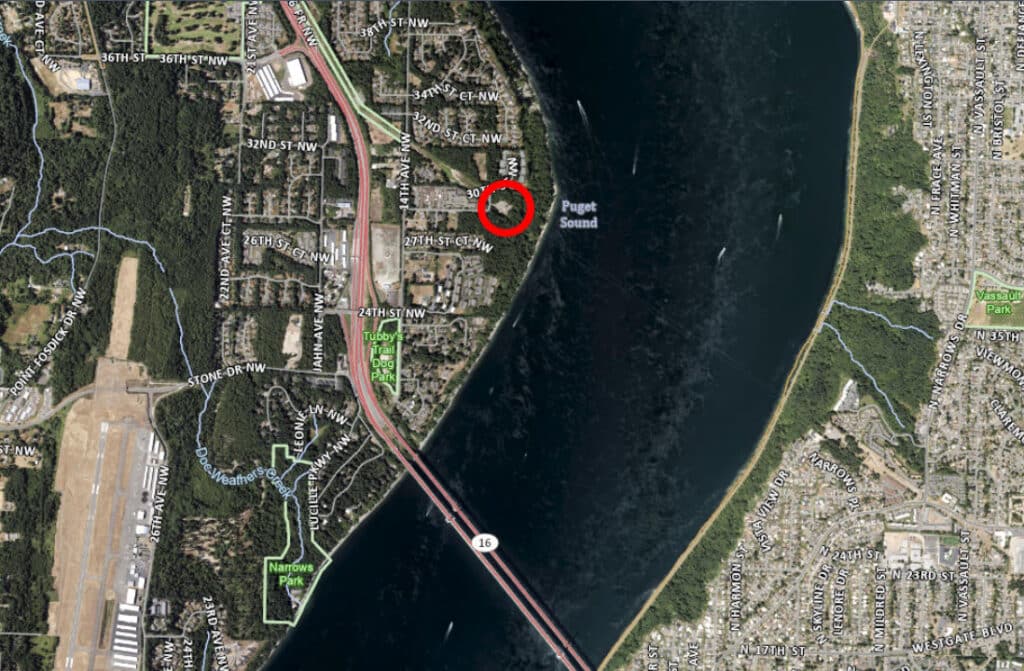

The two original Cushman power line towers on the west side of the narrows were in the same location as the single tower is today. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

While not necessarily a popular activity, many local kids from several generations climbed the towers in their searches for fun and exciting experiences to pass the time. It was a dangerous thing to do, and not simply from the risk of falling to the ground. There was also the all-too-real possibility of being electrocuted by somewhere over 100,000 volts of electricity running through the unshielded cables at the top. In fact, two young people were killed by electrocution on the towers in later years, a 17-year-old boy in 1976, and a 20-year-old man in 1985.

Unlike their replacement, the original Cushman power line towers had no measures to prevent teenaged knuckleheads from climbing the chain-link perimeter fence, starting up the stairs, and climbing around the locked steel door, just a short ways up. No security cameras, no motion detector lights, no alarm sirens, no internet surveillance, and no razor wire.

In contrast, today’s fence has six strands of barbed wire at the top, three of which are laced through endless loops of razor wire. That alone would’ve stopped virtually every trespassing kid in the old days. In addition, there is now a housing development next to the site, so the access road no longer dead-ends at the tower. Cars passing by the fence at irregular intervals to and from the development are another deterrent.

The view from 317 feet up

At least two of the boys had been to the top of the tower before, so it wasn’t something new. What was new was darkness and fireworks. The lack of light wasn’t problematic, but the fireworks turned out to be just that.

Oh, they saw multiple fireworks displays alright, from way up north to way down south. The problem was that all of them were so far away that they could barely be seen, and certainly not enjoyed. Even the ones in not-all-that-far-away Old Town Tacoma appeared so small they weren’t worth watching. A single, hand-held sparkler slowly twirled in a lazy circle would’ve put on a better show.

It was also windy, and it was cold!

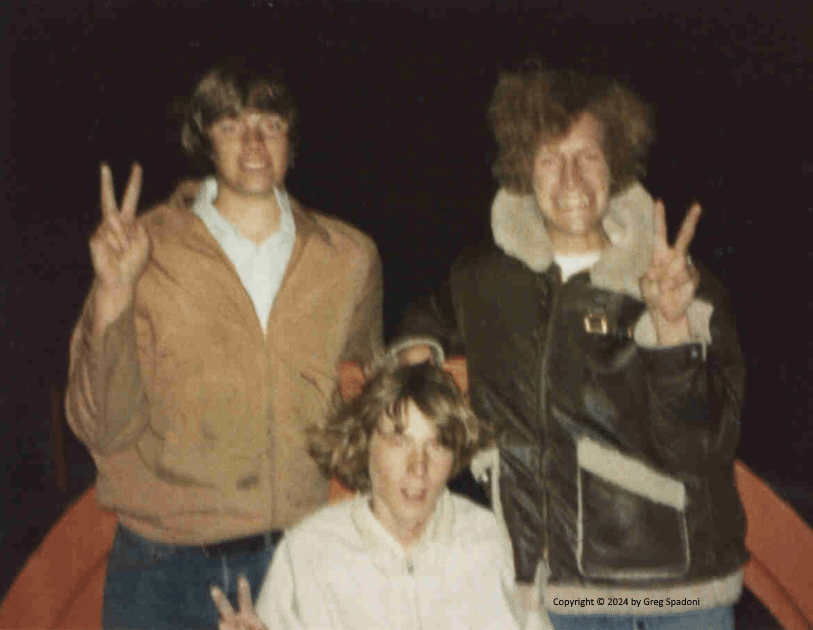

The most interesting image of the entire escapade was not of the far distant fireworks, but the one recorded at the top of the tower with a Kodak Pocket Instamatic camera. The print is of low resolution and the colors are somewhat muted, but unlike the fireworks that night, at least you can tell what you’re looking at when you see it.

In what the advertising of the Eastman Kodak Company used to call a Kodak Moment, this snapshot shows, from left to right, Dennis Hacker, Jim Grady, and Mike Tarbet. On the night of July 4, 1973, they and another classmate climbed one of the old Cushman power line towers at Point Evans on the Narrows. Those towers no longer exist.

No new question this week

At this point, normally we’d set up a new question and say, “We’ll have the answer on July 15.” But because our next column topic is so unusual, we’ll skip the new question bit. Instead, we will mention that the July 15 column will feature a brief look at one of the most fascinating biographies of local history, with threads reaching back to and beyond the Civil War.

In today’s column we contemplated the possibility of the Key Peninsula having an alternate name, and how close that possibility came to becoming a reality. The only practical result of a different name would’ve been slightly different addresses. That wouldn’t have changed anyone’s life in any meaningful way. The July 15 column will set up an infinitely more consequential what-if question. We won’t answer it, because there is no definitive answer. It’s one of those twists-your-mind-into-a-pretzel sorts of things. (There will be no credit given for pointing out the author is already twisted too tight, as that’s not a new observation.)

A challenge has been issued

While correctly answering the question of the alternate names for the Key Peninsula on the Gig Harbor Now Facebook page on June 17, Billy Sehmel issued a challenge to me directly. I was tempted to duck and pretend I didn’t see it (which, technically, I didn’t, because I’m not a Facebook member) but someone sent it to me as a screen shot, so I’m obligated to accept it.

This puts me in a difficult spot however, because by answering his question, “Do you know what local island used to be named Grave Island?” I would use up a possible future topic for Gig Harbor Now and Then. (That alone tells you it’s an excellent question!) And using it up with a simple, straightforward answer would prevent me from blathering on about it with tedious explanations, dull anecdotes, and other boring stuff, which is the very foundation of this column of local history.

Instead of spoiling a possible future question for this column, I’d like to be able to respond this way: Yes, Billy, of course I know what local island used to be named Grave Island. It’s an excellent question, but a rather softball one. Let’s speed it up a little. Do you know the name of the first deeded owner of Grave Island? How about the name of the first known person to live there? And I’ll raise you one with this: What was his profession?

But that’s no good because I’ve previously published most of that information on another website. I’m pretty sure Billy has read it, so will already know the answers to two of the three questions. And what’s the fun of asking questions that can be answered so easily?

Here’s another question that would’ve been great for Billy if he hadn’t already seen the answer on that other website, for it links his ancestors to Grave Island, at least indirectly: What did Henry Sehmel and the first known person to live on Grave Island have in common?

While that’s a pretty wide open question, there is a specific, geographical answer. (Big clue there!) Too bad we’re not going to ask it.

Deed erosion

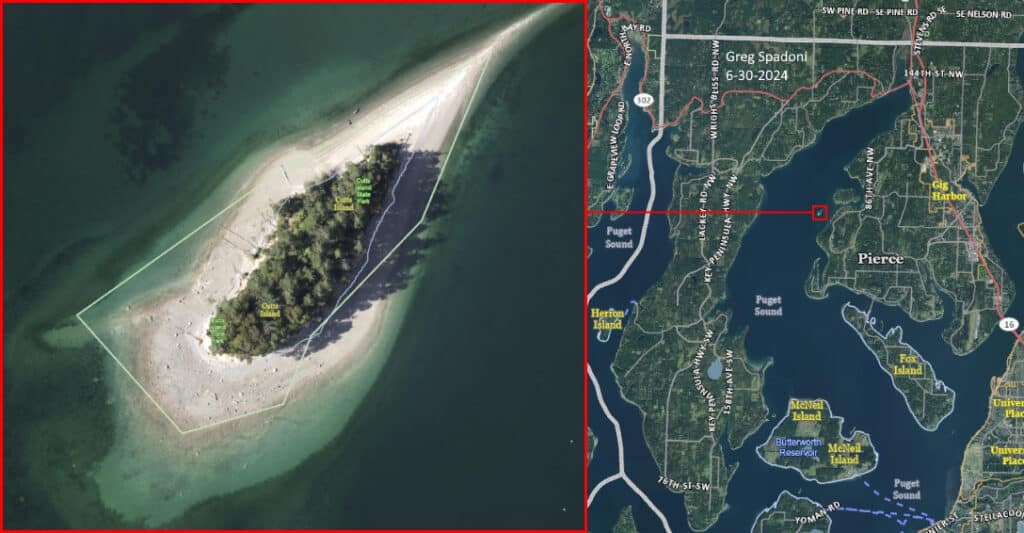

Speaking of “first deeded owner” of a local island, early last month the Harbor History Museum received as a donation the very first deed issued for the ownership of Dead Man’s Island (currently known as Cutts Island State Park), near Raft Island in Rosedale. With the federal government as grantor, and Carl Lorenz as grantee, it was drawn up in 1891, although the transaction took place in 1890. Acquired under the authority of the Preemption Act of 1841, the purchase of that island could’ve lead to a fine, fine question of the week: How much did Lorenz pay for the 5.5 acres of Dead Man’s Island in 1890? But because we’ve already noted that there will be no question this week, the answer is $13.75.

Dead Man’s Island, aka Cutts Island State Park, is in South Rosedale, due east of the Right Hand Peninsula. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

It’s always interesting to convert old dollar amounts into current values. Thirteen dollars and seventy-five cents in 1890 is equivalent to about $474.55 today. Who in their right mind would pay that kind of money for Cutts Island State Park?

ME! ME! ME! ME!

The mention of 5.5 acres on the original deed from 1891 is sort of a disturbing revelation because the island’s been eroded to just two acres today. The trend is not a good one.

I’d still buy it for 474 bucks, though. In fact, I’d probably go as high as five hundred.

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.